| "My spirit you can certainly have, and anyone can have it who remembers it and wants it." — Socrates, Barefoot in Athens |

The infamous trial and execution of Socrates in 399 B.C., as recounted by his then-mentee, Plato, fascinated me ever since first reading them in undergrad. The vague charge against the father of Western philosophy, corrupting the youth of Athens, and moreover, Socrates' decision to drink the poison hemlock instead of flee into exile, was frustrating and an enigma.

Why would a critical and independent-minded man accept the unjust death sentence—a sentence thrown down because he asked uncomfortable questions to people in the streets? Fast forward ten years after my Intro to Political Philosophy course at Penn State to a few weeks ago, when I stumbled across Barefoot in Athens, a two-act drama by American playwright Maxwell Anderson.

I was hooked. The 90-page play is simple, powerful, and uniquely relevant again in the age of so-called hate-speech, safe spaces, trigger warnings and fetishistic phobia-labeling. While reading Barefoot, I wouldn't help but think of Jordan Peterson, the Canadian professor whose free speech against compelled speech brought him to the forefront of a profoundly divided conversation on tolerance, civility, and freedom.

And now as I'm writing this, I'm thinking back to a hero of mine, Flemming Rose, who in September 2005, he commissioned and published twelve cartoons about Islam, prompted by his perception of the European media’s self-censorship. One of those cartoons, an image of the prophet Muhammad with a bomb in his hair, sparked what would become known as the “cartoon crisis,” during which both peaceful protests and violence erupted across the world.

Barefoot in Athens spotlights and celebrates that intransigent spirit of free inquiry and truth-seeking of Socrates, of some—but ultimately not enough—Athenians. And more than that, the play asks of contemporary readers, "Is it better to die a free man or to live as a slave?" And whatever your answer, to quote Socrates himself, "Why?" [JG]

Why would a critical and independent-minded man accept the unjust death sentence—a sentence thrown down because he asked uncomfortable questions to people in the streets? Fast forward ten years after my Intro to Political Philosophy course at Penn State to a few weeks ago, when I stumbled across Barefoot in Athens, a two-act drama by American playwright Maxwell Anderson.

I was hooked. The 90-page play is simple, powerful, and uniquely relevant again in the age of so-called hate-speech, safe spaces, trigger warnings and fetishistic phobia-labeling. While reading Barefoot, I wouldn't help but think of Jordan Peterson, the Canadian professor whose free speech against compelled speech brought him to the forefront of a profoundly divided conversation on tolerance, civility, and freedom.

And now as I'm writing this, I'm thinking back to a hero of mine, Flemming Rose, who in September 2005, he commissioned and published twelve cartoons about Islam, prompted by his perception of the European media’s self-censorship. One of those cartoons, an image of the prophet Muhammad with a bomb in his hair, sparked what would become known as the “cartoon crisis,” during which both peaceful protests and violence erupted across the world.

Barefoot in Athens spotlights and celebrates that intransigent spirit of free inquiry and truth-seeking of Socrates, of some—but ultimately not enough—Athenians. And more than that, the play asks of contemporary readers, "Is it better to die a free man or to live as a slave?" And whatever your answer, to quote Socrates himself, "Why?" [JG]

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

| Maxwell Anderson (1888-1959) was an American playwright, poet, and and journalist. Scanning through his extensive list of works, a few caught my eye that I've added to my reading pile: his play Joan of Lorraine, which was adapted for the screen and stars Ingrid Bergman as Joan of Arc, and also Anderson's 1934 play Valley Forge, which reimagines the harsh winter encampment of George Washington's ragtag army. Will report back soon! |

QUOTES

| 5. "We...bring this charge against Socrates—that he is guilty of crime, first because he does not worship the gods of our city, but introduces new divinities of his own; second, because he corrupts the thinking of our young men. We make this charge and demand an immediate trial. The penalty due is death." — Crito 4. "Nothing could be healthier than to bring the whole thing into the open, right out in the good sunlight before every man in Athens with every possible charge levelled against me and full discussion of politics, gods, and men." — Socrates 3. "I must say that the search for truth is more sacred than any god, more desirable than any woman, more hopeful than any child, more lovely than any city, even our own! If you have not seen this, you will vote against me, and you should. But you are men of Athens, and you have seen it or Athens would not be here, would not from the beginning have been possible. — Socrates 2. "Athens has always seemed to me a sort of mad miracle of a city, flashing out in all directions, a great city for no discoverable reason. But now I see that Athens is driven and made miraculous by the same urge that has sent me searching your streets. It is the Athenian search for truth, the Athenian hunger for facts, the endless curiosity of the Athenian mind, that has made Athens unlike any other city. This is a city drenched with light—the light of frank and restless inquiry—and this light has flooded every corner of our lives: our courts, our theater, our athletic games, our markets—even the open architecture of the temples of our gods! ... Shut out the light and close our minds and we shall be like a million cities of the past that came up out of mud, and worshipped darkness a little while, and went back, forgotten, in the darkness!" — Socrates 1. "My spirit you can certainly have, and anyone can have it who remembers it and wants it." — Socrates |

| " Be of good courage, Xantippe, and lose nothing of Socrates. Knowing how great he was, think of his life, not of his death. Still, the death, too, if you consider it carefully, appears noble and excellent. Farewell. " — Friend Xenophon to Xantippe, Socrates' widow, in a letter post-trial and execution |

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

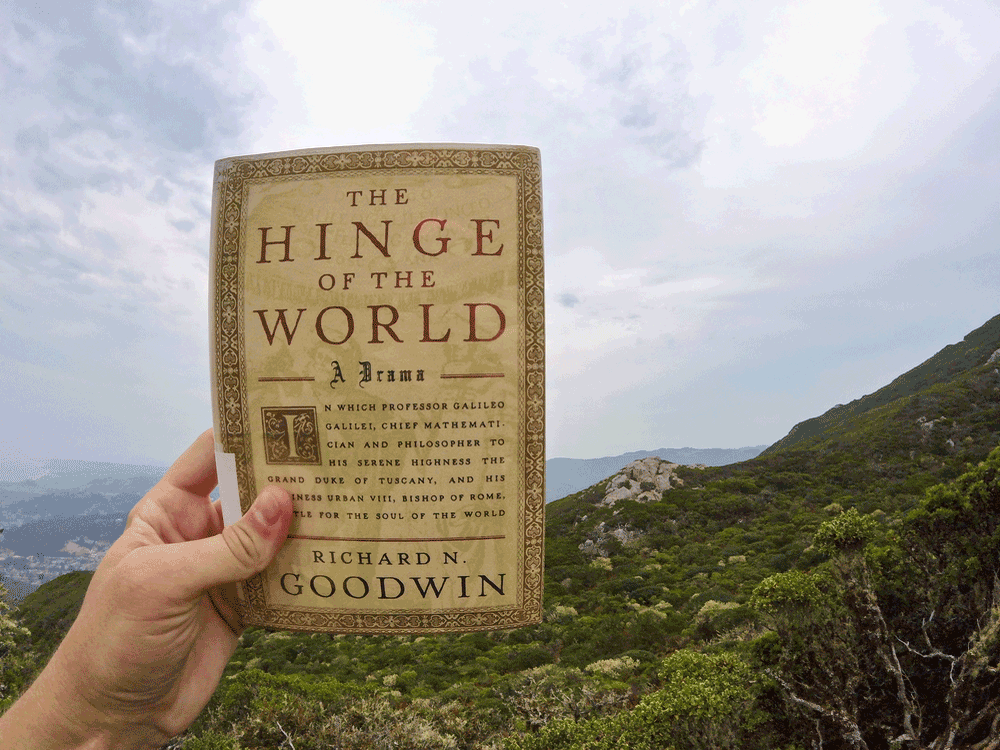

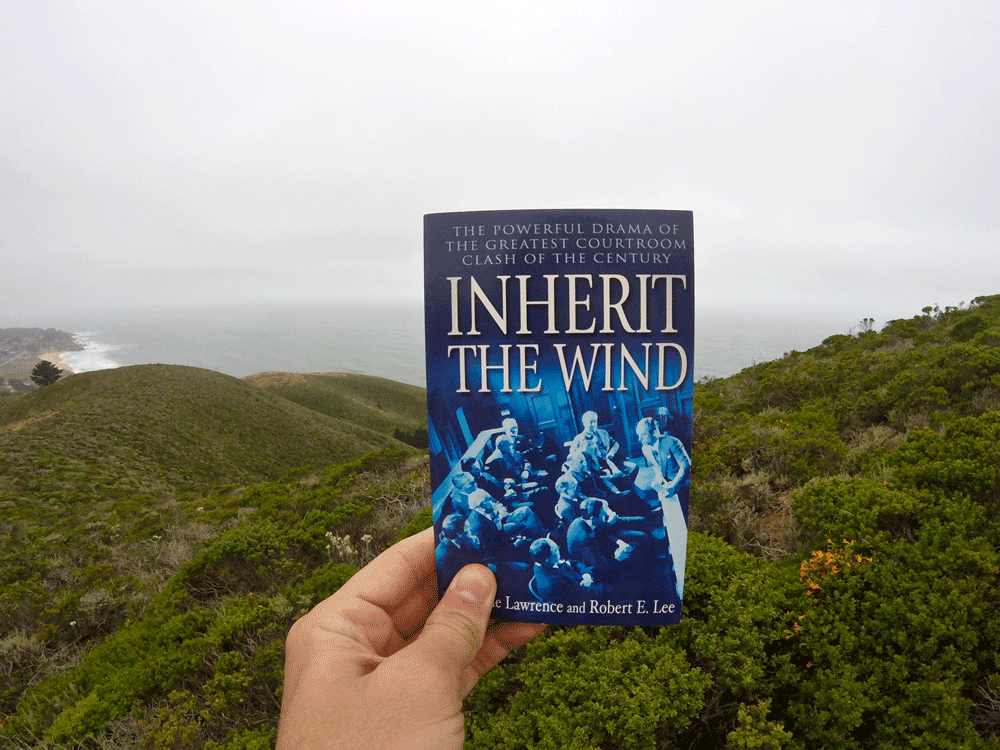

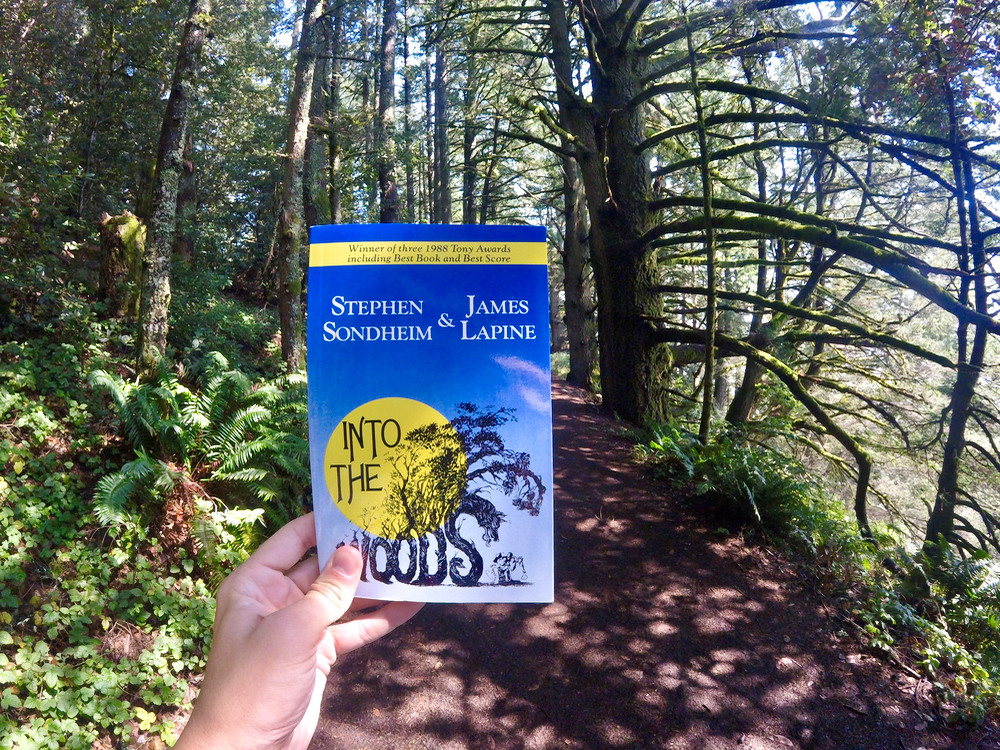

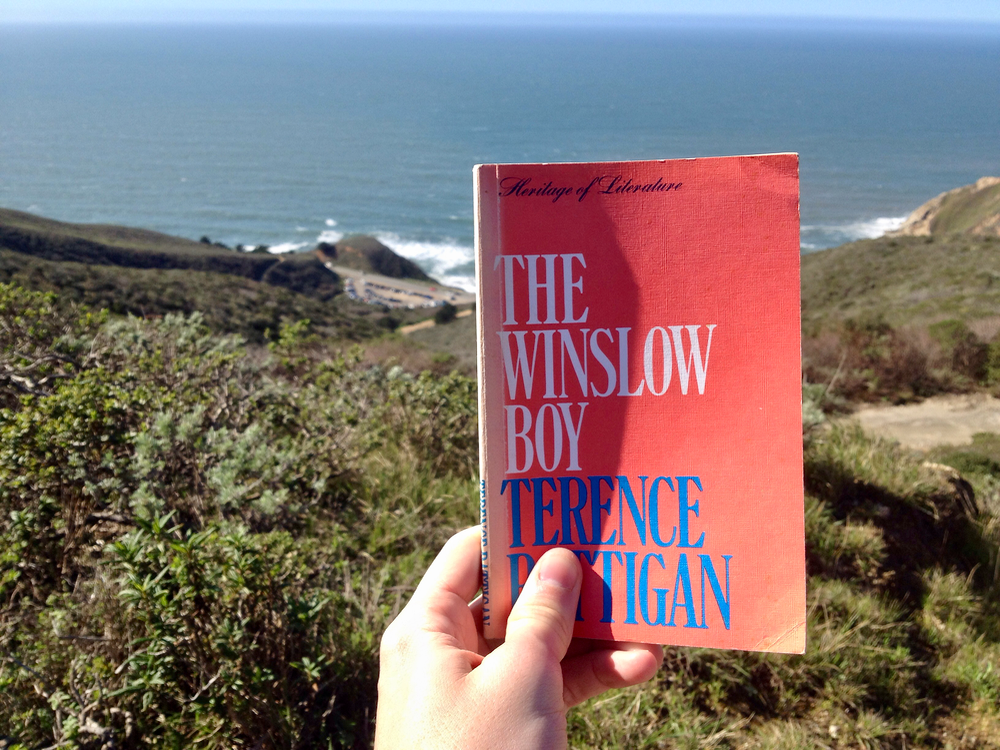

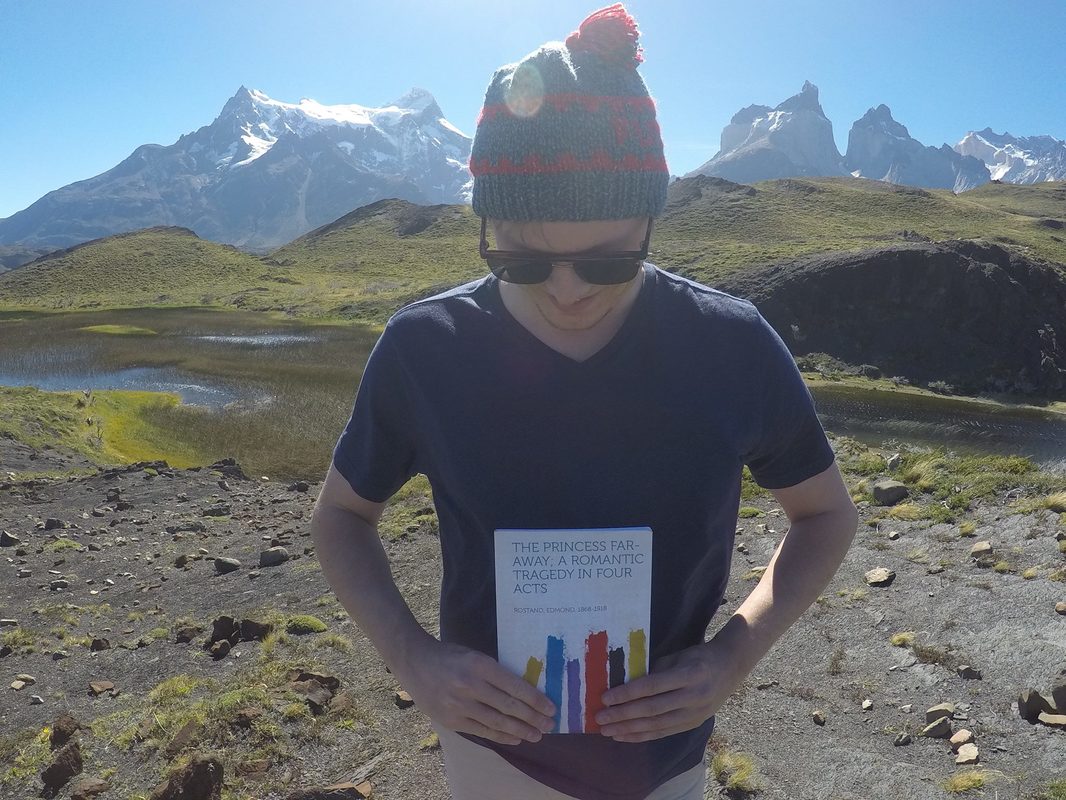

| THE HINGE OF THE WORLD A play about Galileo vs. the Inquisition Richard N. Goodwin INHERIT THE WIND A play about Darwin vs. Religion in schools Jerome Lawrence & Robert E. Lee INTO THE WOODS A play of Grimm's fairy tale characters Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine | THE WINSLOW BOY A play about justice in matters big and small Terence Rattigan ROMANTICS A 'Romeo & Juliet' inspired comedy play Edmond Rostand THE PRINCESS FAR AWAY A play based on a true medieval love story Edmond Rostand |