"It was with the wax of his own soul

that he formed that of Cyrano."

— Rosemonde Gerard, Edmond Rostand's wife

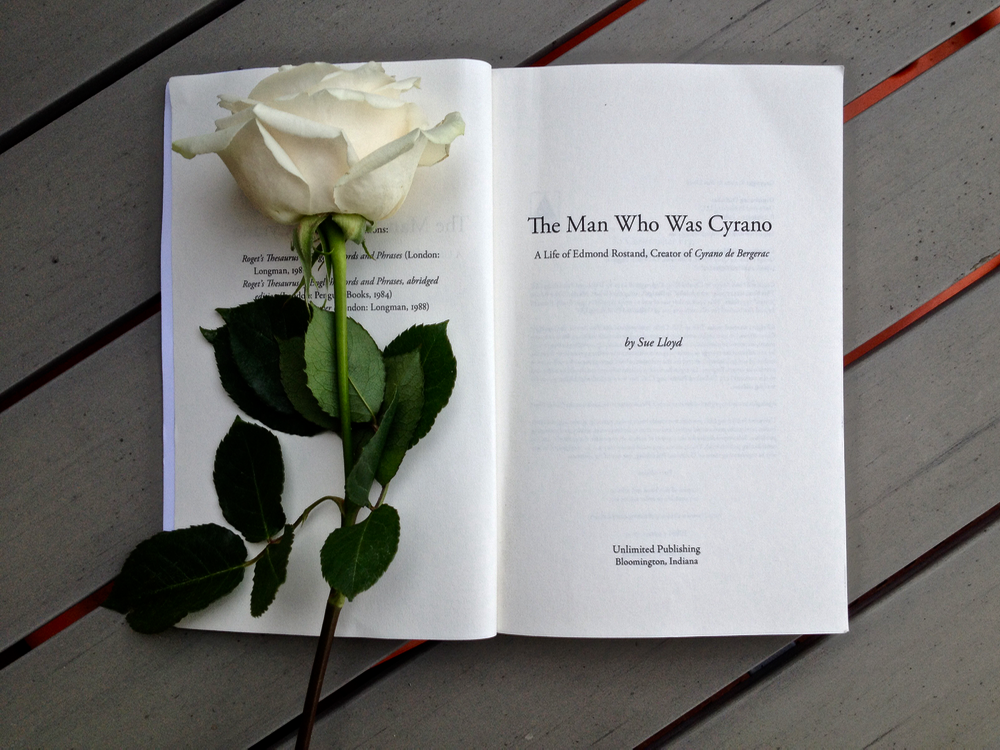

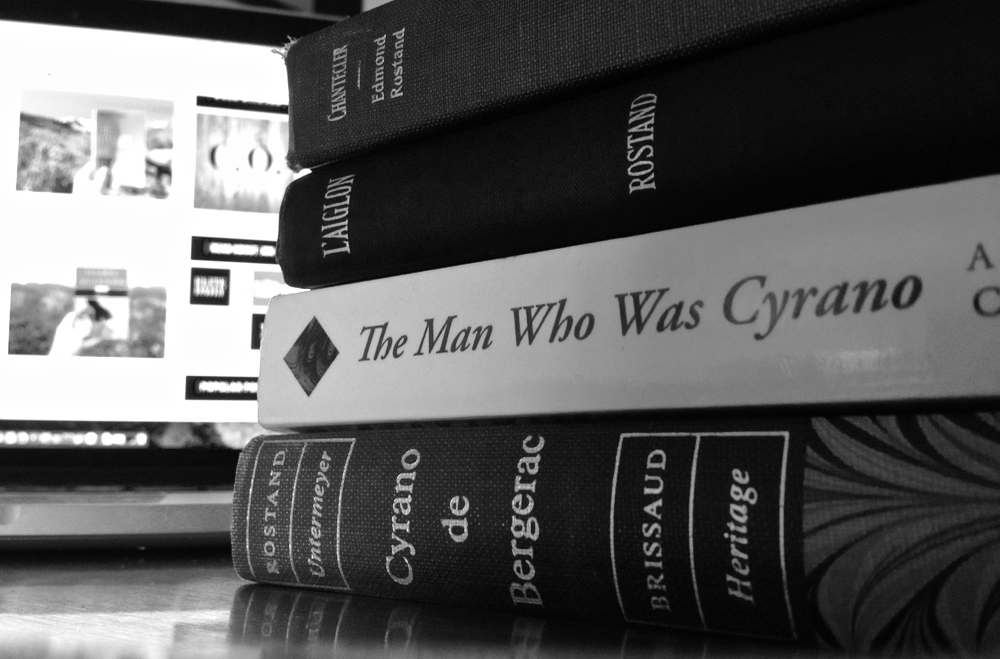

Sue Lloyd's biography of Edmond Rostand is simply incredible. After reading the French playwright's best-known work Cyrano de Bergerac last December, and then in early 2017 some of his other plays (Chantecler, The Eaglet, and The Princess Far Away), I've found a new favorite writer. Rostand's grand view of life's possibilities, his passionate defense of idealism, pride, and integrity, his poetic wit, and dramatic imagination — all this exuded in his art is more that enough, but meeting the man by way of Lloyd's passionate and precise research was the greatest biographical experience I've ever had.

Organized into five acts, The Man Who Was Cyrano traces Edmond's childhood and adolescence, rising dramatic aspirations, climactic artistic achievements, and his final years. She brilliantly brings the artist's eccentricities and passions to life with the help of first-hand letters and work notes, anecdotes and accounts from friends, families, and colleagues, a trove of historic documents, and her own detective work.

Organized into five acts, The Man Who Was Cyrano traces Edmond's childhood and adolescence, rising dramatic aspirations, climactic artistic achievements, and his final years. She brilliantly brings the artist's eccentricities and passions to life with the help of first-hand letters and work notes, anecdotes and accounts from friends, families, and colleagues, a trove of historic documents, and her own detective work.

FAVORITE SECTIONS

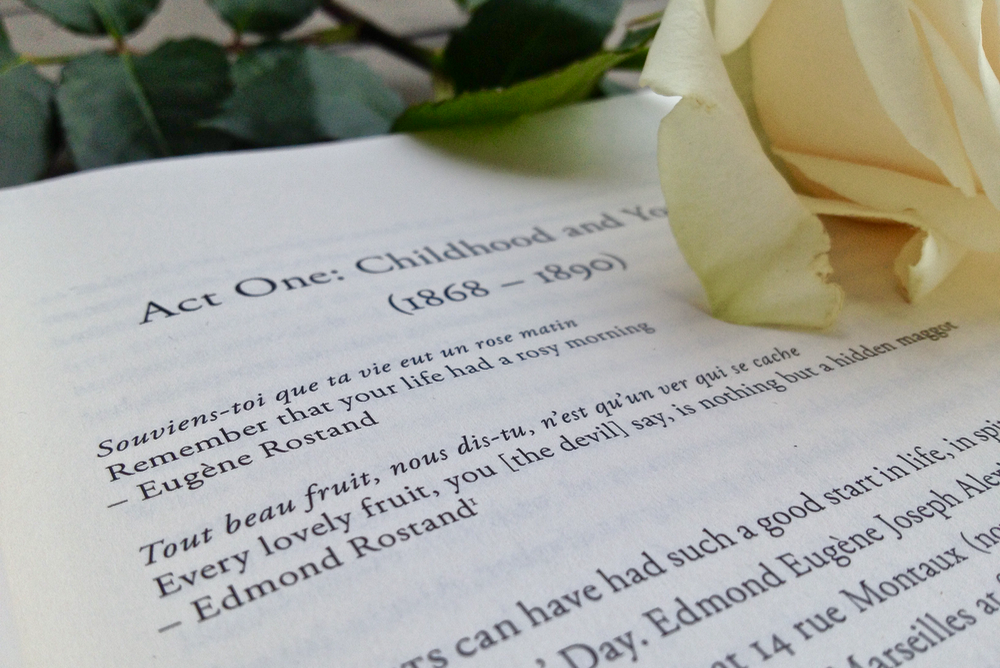

Act One: Childhood and Youth (1868 - 1890)

{ * } Born in 1868 on April Fool's Day to a successful economist and poet Eugene Rostand, Edmond, or 'Eddie,' would grow up to be known by his family for his "fastidiousness," (6) refusing to wear any garment with a spot or stain or mark on it. He quickly became fascinated with the 17th Century, perhaps in part due to the ribbons, plumes, and colors of their wardrobes, which were brought to life on stage in Marseille.

{ * } In school, one of Eddie's teachers chastised him once, claiming, "You set a bad example. You daydream all the time." (11) Around then, the boy used a poem written by a friend to woo a childhood sweetheart(!), and in geography class he wrote an essay on the Mediterranean Sea that was devoid of facts and left his grade wanting, but the class enthralled with his poetic descriptions.

{ * } Eddie loved the works of Alphonse Daudet and Gautier's Le Capitaine Fracasse for its brave, broke hero, and pure, beautiful heroine. Later, Eddie fell in love with Alexander Dumas' The Three Musketeers as well as the poetry by René Doumic and Georges d'Esparbès. The late 16th Century too, with its post-Renaissance / early-Enlightenment shedding of artistic and religious rules attracted him.

{ * } Eddie's best friend Henry de Gorsse, who would also grow up to be a playwright, recalled floating flowers down the river, and exploring the woods, and ruins of Castel-Viel. (14) Gorsse described Rostand as a jokester, changing clocks and freeing penned deer who would then follow him home. There's an episode of Eddie unblocking a river upstream, because a priest had diverted it to create waterfalls in the parish. The boy didn't like the idea of charging people to see something beautiful and natural, but upon being caught gloating in the parish by some unhappy customers, Eddie opened his purse and paid 25 francs, the money he and Henry had been saving to buy fireworks.

{ * } When Eddie and Henry were twelve, Eddie almost fought a Spaniard for mistreating a Greek girl at a dance; seventeen years later Eddie would remind Henry of the incident which he includes in the first act of Cyrano de Bergerac — Cyrano runs to help his friend against one hundred men. (16) Moreover, Eddie loved to ride horseback and explore the Haute-Garonne. He used the hills and town names for those of the Cadets in Cyrano.

Act Two: The Aspiring Dramatist (1890 - 1897)

{ * } In 1887 summer, 19-year-old Edmond meets Rosemonde Gerard, a 21-year old poet, whom his father Eugene had met on the train and invited her to come over — presumably to meet his son. Eddie recalled seeing her framed in the doorway lit by the sun, her blonde hair like a halo. (39) They were engaged in 1888 and Eddie began writing love poetry and writing with more urgency. His first play, The Red Glove, did terrible in theaters through and was cut after 15 days.

{ * } In Le Reve, a poem Edmond destroyed, "A poet is in love with a woman he has never met when the possibility arises of actually meeting her, he dies rather than risk losing his ideal picture of her." (38) Edmond though, wanted to write a Romeo and Juliet, divided-lovers type play, but with a happy ending, which culminated into The Romancers, a comedy. Post-feedback from the committee, he went into depression and could not write for two months, this followed his month of elation writing it. Rosemonde helped him to learn to read it faster, and cut some unnecessary stage direction, fitting it into 60 minutes not 75. It premiered to great success when Rostand was 26.

{ * } This elation-depression swing in Edmond's creative process was the first inner battle of a war he would fight for the rest of his life, struggling to raise his work to his exacting, perfectionism-type standards. In a poem of his "Chanson dans le Soir" (Song in the Night), a poet is moved to tears by the simple sound of a boy's song rising out of a valley in the peace of the autumn evening: 'Shall I never be more than a vibrating lyre? Both sad and charming, moved by slighly mocking...Alas here are better things to do!' (68) Edmond's clash of artistic melancholy and self-criticism with his desire to create beauty.

{ * } By now, Rostand adored the late-French novelist and playwright Victor Hugo, whom he viewed as a secondary father figure, whose idealism, patriotism, dramatic heroes, and enlightened language was what Rostand sought to aspire towards and resurrect in France with what Rostand called, "...a smaller, lighter canvas" (157)

Act Three: Cyrano de Bergerac and L'Aiglon (1897-1900)

{ * } "I wrote Cyrano de Bergerac in accordance with my own tastes, with love and pleasure, and also, I maintain, with the idea of struggling against the tendencies of the time, tendencies which to be honest, upset and revolted me." — Edmond Rostand

{ * } "It was with the wax of his own soul that [Rostand] formed that of Cyrano." — Rosemonde Gerard, Rostand's wife (127)

{ * } "Forgive me, friend, for having dragged you into this disastrous adventure," Rostand cried. "There is nothing to forgive...You have given me a masterpiece," — Benoît-Constant Coquelin, playing Cyrano. (Rostand's depression and chronic perfectionism nearly cancelled the play! Rosemonde encouraged him again and again throughout, and even stepped in to play Roxane when the actress had a sore throat and didn't want to risk losing her voice. She also brought real bread loaves and legs of ham to make Ragueneau's cafe in Act II more genuine. (135-7)

{ * } The opening performance had 40+ curtain calls, people began to sing the Marseille, and two writers who attended and were committed to fighting a duel to the death the next morning in the public square, made up peacefully. (138)

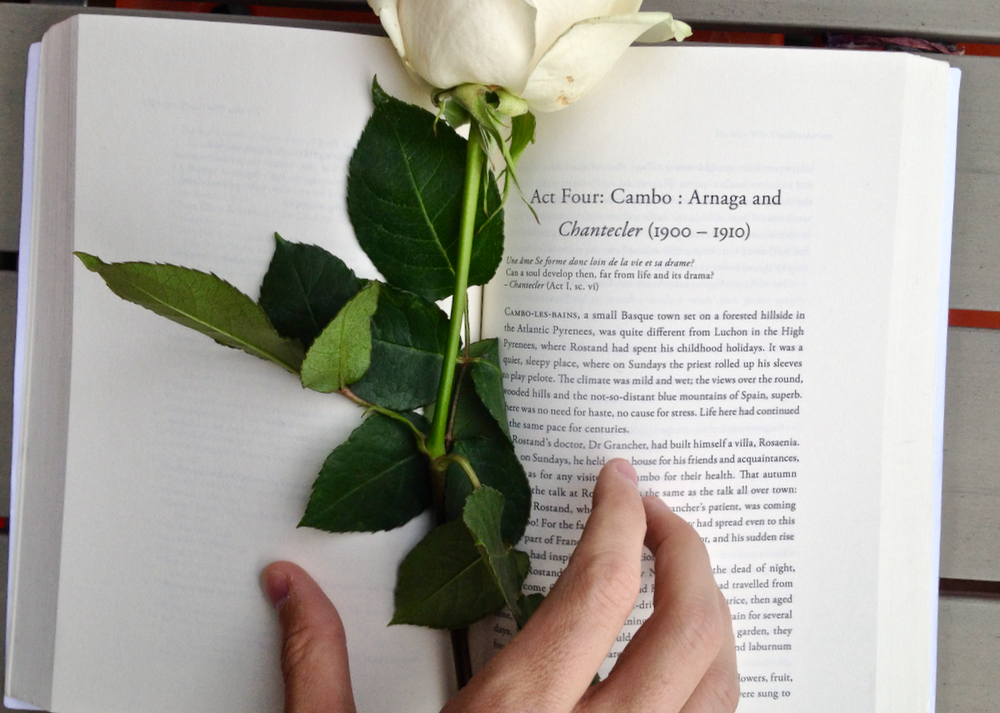

Act Four: Cambo (1900 - 1910)

{ * } Edmond's continuously frail health led him and his family to move to Cambo, in the Pyrenees mountains. He designed his own house there, and enjoyed quiet gardens and forests and the distance from the critics and what he viewed as cynical culture that had infected Paris. Life in Cambo was slow, quiet, wooded; he had blue hydrangeas, fruit trees, berried holly, camellias, and laburnum. He bought white doves, white dogs, white cats, white swans, to glide beside a small boat on the canal used to travel down the length of the garden.

{ * } "Rostand's garden at Arnaga was as much an artistic creation as his house and his plays. He had taken great pleasure in designing it, and was forever thinking of new ways to improve it. The formal garden now ran the full length of the plateau, stretching away. Towards the distant mountains, with its geometrical parterres full of vivid flowers, its lawns and pools and fountains, the whole framed by full-grown trees. Facing the classical orangery across the formal garden was a green arbor, approached through a rose garden, where the busts of Shakespeare, Victor Hugo, and Cervantes overlooked the poet as he worked." — Sue Lloyd, 272

{ * } Rostand also bought a white Arab mare, Zobeide, to explore Cambo with, and upon coming to a farm and seeing the hens, dogs, cats, and a rooster enter, he found the idea for his next play: "He enters, imperious, proud, with disdain in his look and in the rhythmic movement of his head, and something heroic and irresistible in his walk. He advances like a swordsman, you'd have thought him a man looking for amorous or deadly adventures, or a king amongst his subjects..."

{ * } Chantecler would be Rostand's last completed play, and I think his most personal and original. There is no historical context to draw on, unlike his other major works. It's a pure fantasy, in which an idealistic rooster, who lords over the farm, draws the envy and malice of the other farm animals. Moreover, the rooster must question his most sacred value — his song, his Cock-a-doodle-doo — which, may in fact not cause the sun to rise as he believes, begging the question, if his work is not in fact true, is life worth living?

{ * } "I sing by opening my heart. Do you know what it costs me?" — Chantecler to Blackbird in Act I, reflects both Rostand's elation-depression complex he brought to his art: work demands great effort, but it alone make life worth living. And work is a sacred, moral task, for both Rostand and his heroes.

Act Five: The Last Years (1910 - 1918)

{ * } Edmond's list of unfinished poems and plays add up, each interesting in their own way though: a trilogy of plays including Faust, Don Juan, and Polichinelle about the importance of idealism and the destructive power of doubt and cynicism in one's life. Rostand also thought of Jeanne d'Arc, but wanted to call it "Le Couer," The Heart. According to legend Joan's heart did not burn. In Rostand's version a young foundry worker would rescue the heart from the pyre and throw it into the molten metal used for making bells, so that Joan of Arc's patriotism would ring out from the steeples across France. (196). He also considered making Chanson de Roland into a modern patriotic epic.

{ * } Rostand began a prose-play about Helen of Troy, and then The Twelve Tasks, about the humiliation of Hercules by Omphale. In it, Hercules has completed the twelve tasks and is resting on his laurels. In a game with Omphale, she shows him that if you rest on them, you kill them. "You're no longer a hero if you stop working." (249)

{ * } He did though finish a poem called The Sacred Wood, in which a couple breaks down in a car in the 20th Century. The Greek gods discover the car and mend it. Aeolus inflates the tires; Vulcan inspects the motor; Psyche lights the headlights; Morpheus puts the couple to sleep. The gods go on a joy ride and then return the car. The couple wake up, amazed that the car now works, and drive off. We see cupid in the trunk plotting mischief (242)

{ * } Rostand missed his wife's and son's play, A Good Little Devil, working instead on his Don Juan play. Their play in 1911 was a success, even amongst critics who disliked Chantecler.

{ * } "One is never happy. I am an anxious man. My unhappiness comes from my anxiety. At rest, I doubt everything. I am suspicious of fate and of things and of people. And this spoils my joys." — Edmond Rostand

{JG}

{ * } Born in 1868 on April Fool's Day to a successful economist and poet Eugene Rostand, Edmond, or 'Eddie,' would grow up to be known by his family for his "fastidiousness," (6) refusing to wear any garment with a spot or stain or mark on it. He quickly became fascinated with the 17th Century, perhaps in part due to the ribbons, plumes, and colors of their wardrobes, which were brought to life on stage in Marseille.

{ * } In school, one of Eddie's teachers chastised him once, claiming, "You set a bad example. You daydream all the time." (11) Around then, the boy used a poem written by a friend to woo a childhood sweetheart(!), and in geography class he wrote an essay on the Mediterranean Sea that was devoid of facts and left his grade wanting, but the class enthralled with his poetic descriptions.

{ * } Eddie loved the works of Alphonse Daudet and Gautier's Le Capitaine Fracasse for its brave, broke hero, and pure, beautiful heroine. Later, Eddie fell in love with Alexander Dumas' The Three Musketeers as well as the poetry by René Doumic and Georges d'Esparbès. The late 16th Century too, with its post-Renaissance / early-Enlightenment shedding of artistic and religious rules attracted him.

{ * } Eddie's best friend Henry de Gorsse, who would also grow up to be a playwright, recalled floating flowers down the river, and exploring the woods, and ruins of Castel-Viel. (14) Gorsse described Rostand as a jokester, changing clocks and freeing penned deer who would then follow him home. There's an episode of Eddie unblocking a river upstream, because a priest had diverted it to create waterfalls in the parish. The boy didn't like the idea of charging people to see something beautiful and natural, but upon being caught gloating in the parish by some unhappy customers, Eddie opened his purse and paid 25 francs, the money he and Henry had been saving to buy fireworks.

{ * } When Eddie and Henry were twelve, Eddie almost fought a Spaniard for mistreating a Greek girl at a dance; seventeen years later Eddie would remind Henry of the incident which he includes in the first act of Cyrano de Bergerac — Cyrano runs to help his friend against one hundred men. (16) Moreover, Eddie loved to ride horseback and explore the Haute-Garonne. He used the hills and town names for those of the Cadets in Cyrano.

Act Two: The Aspiring Dramatist (1890 - 1897)

{ * } In 1887 summer, 19-year-old Edmond meets Rosemonde Gerard, a 21-year old poet, whom his father Eugene had met on the train and invited her to come over — presumably to meet his son. Eddie recalled seeing her framed in the doorway lit by the sun, her blonde hair like a halo. (39) They were engaged in 1888 and Eddie began writing love poetry and writing with more urgency. His first play, The Red Glove, did terrible in theaters through and was cut after 15 days.

{ * } In Le Reve, a poem Edmond destroyed, "A poet is in love with a woman he has never met when the possibility arises of actually meeting her, he dies rather than risk losing his ideal picture of her." (38) Edmond though, wanted to write a Romeo and Juliet, divided-lovers type play, but with a happy ending, which culminated into The Romancers, a comedy. Post-feedback from the committee, he went into depression and could not write for two months, this followed his month of elation writing it. Rosemonde helped him to learn to read it faster, and cut some unnecessary stage direction, fitting it into 60 minutes not 75. It premiered to great success when Rostand was 26.

{ * } This elation-depression swing in Edmond's creative process was the first inner battle of a war he would fight for the rest of his life, struggling to raise his work to his exacting, perfectionism-type standards. In a poem of his "Chanson dans le Soir" (Song in the Night), a poet is moved to tears by the simple sound of a boy's song rising out of a valley in the peace of the autumn evening: 'Shall I never be more than a vibrating lyre? Both sad and charming, moved by slighly mocking...Alas here are better things to do!' (68) Edmond's clash of artistic melancholy and self-criticism with his desire to create beauty.

{ * } By now, Rostand adored the late-French novelist and playwright Victor Hugo, whom he viewed as a secondary father figure, whose idealism, patriotism, dramatic heroes, and enlightened language was what Rostand sought to aspire towards and resurrect in France with what Rostand called, "...a smaller, lighter canvas" (157)

Act Three: Cyrano de Bergerac and L'Aiglon (1897-1900)

{ * } "I wrote Cyrano de Bergerac in accordance with my own tastes, with love and pleasure, and also, I maintain, with the idea of struggling against the tendencies of the time, tendencies which to be honest, upset and revolted me." — Edmond Rostand

{ * } "It was with the wax of his own soul that [Rostand] formed that of Cyrano." — Rosemonde Gerard, Rostand's wife (127)

{ * } "Forgive me, friend, for having dragged you into this disastrous adventure," Rostand cried. "There is nothing to forgive...You have given me a masterpiece," — Benoît-Constant Coquelin, playing Cyrano. (Rostand's depression and chronic perfectionism nearly cancelled the play! Rosemonde encouraged him again and again throughout, and even stepped in to play Roxane when the actress had a sore throat and didn't want to risk losing her voice. She also brought real bread loaves and legs of ham to make Ragueneau's cafe in Act II more genuine. (135-7)

{ * } The opening performance had 40+ curtain calls, people began to sing the Marseille, and two writers who attended and were committed to fighting a duel to the death the next morning in the public square, made up peacefully. (138)

Act Four: Cambo (1900 - 1910)

{ * } Edmond's continuously frail health led him and his family to move to Cambo, in the Pyrenees mountains. He designed his own house there, and enjoyed quiet gardens and forests and the distance from the critics and what he viewed as cynical culture that had infected Paris. Life in Cambo was slow, quiet, wooded; he had blue hydrangeas, fruit trees, berried holly, camellias, and laburnum. He bought white doves, white dogs, white cats, white swans, to glide beside a small boat on the canal used to travel down the length of the garden.

{ * } "Rostand's garden at Arnaga was as much an artistic creation as his house and his plays. He had taken great pleasure in designing it, and was forever thinking of new ways to improve it. The formal garden now ran the full length of the plateau, stretching away. Towards the distant mountains, with its geometrical parterres full of vivid flowers, its lawns and pools and fountains, the whole framed by full-grown trees. Facing the classical orangery across the formal garden was a green arbor, approached through a rose garden, where the busts of Shakespeare, Victor Hugo, and Cervantes overlooked the poet as he worked." — Sue Lloyd, 272

{ * } Rostand also bought a white Arab mare, Zobeide, to explore Cambo with, and upon coming to a farm and seeing the hens, dogs, cats, and a rooster enter, he found the idea for his next play: "He enters, imperious, proud, with disdain in his look and in the rhythmic movement of his head, and something heroic and irresistible in his walk. He advances like a swordsman, you'd have thought him a man looking for amorous or deadly adventures, or a king amongst his subjects..."

{ * } Chantecler would be Rostand's last completed play, and I think his most personal and original. There is no historical context to draw on, unlike his other major works. It's a pure fantasy, in which an idealistic rooster, who lords over the farm, draws the envy and malice of the other farm animals. Moreover, the rooster must question his most sacred value — his song, his Cock-a-doodle-doo — which, may in fact not cause the sun to rise as he believes, begging the question, if his work is not in fact true, is life worth living?

{ * } "I sing by opening my heart. Do you know what it costs me?" — Chantecler to Blackbird in Act I, reflects both Rostand's elation-depression complex he brought to his art: work demands great effort, but it alone make life worth living. And work is a sacred, moral task, for both Rostand and his heroes.

Act Five: The Last Years (1910 - 1918)

{ * } Edmond's list of unfinished poems and plays add up, each interesting in their own way though: a trilogy of plays including Faust, Don Juan, and Polichinelle about the importance of idealism and the destructive power of doubt and cynicism in one's life. Rostand also thought of Jeanne d'Arc, but wanted to call it "Le Couer," The Heart. According to legend Joan's heart did not burn. In Rostand's version a young foundry worker would rescue the heart from the pyre and throw it into the molten metal used for making bells, so that Joan of Arc's patriotism would ring out from the steeples across France. (196). He also considered making Chanson de Roland into a modern patriotic epic.

{ * } Rostand began a prose-play about Helen of Troy, and then The Twelve Tasks, about the humiliation of Hercules by Omphale. In it, Hercules has completed the twelve tasks and is resting on his laurels. In a game with Omphale, she shows him that if you rest on them, you kill them. "You're no longer a hero if you stop working." (249)

{ * } He did though finish a poem called The Sacred Wood, in which a couple breaks down in a car in the 20th Century. The Greek gods discover the car and mend it. Aeolus inflates the tires; Vulcan inspects the motor; Psyche lights the headlights; Morpheus puts the couple to sleep. The gods go on a joy ride and then return the car. The couple wake up, amazed that the car now works, and drive off. We see cupid in the trunk plotting mischief (242)

{ * } Rostand missed his wife's and son's play, A Good Little Devil, working instead on his Don Juan play. Their play in 1911 was a success, even amongst critics who disliked Chantecler.

{ * } "One is never happy. I am an anxious man. My unhappiness comes from my anxiety. At rest, I doubt everything. I am suspicious of fate and of things and of people. And this spoils my joys." — Edmond Rostand

{JG}

FAVORITE QUOTES

{ 10 }

"My son, my dear son, when you become a man and read these verses where I name you, trembling, remember that your life had a rosy morning, a bright dawn, and think of those whose fate is painful, dark, and sad right from their birth; who never had a dawn, and never knew but shade, remember these are your brothers — go towards them." — Eugene Rostand, Edmond's father

{ 9 }

"What outward elegance remained [in 19th Century France] was only for show, masking grossness and lack of true feeling. In matters of the heart, courtesy and chivalry were made to seem ridiculous, and women were no longer accorded special respect. Rostand believed that even the French language had deteriorated from "the beautiful, pure, rather ceremonious, language of former times." There was more to Edmond's distaste for the materialism of his times than a simple nostalgia for a lost golden age. His attitude was positive, not negative. He was inspired his love of poetry to yearn for a life transformed by idealism, just as everyday things are transformed by the power of the...sun." (38)

{ 8 }

"Rostand's garden at Arnaga was as much an artistic creation as his house and his plays. He had taken great pleasure in designing it, and was forever thinking of new ways to improve it. The formal garden now ran the full length of the plateau, stretching away . towards the distant mountains, with its geometrical parterres full of vivid flowers, its lawns and pools and fountains, the whole framed by full-grown trees. Facing the classical orangery across the formal garden was a green arbour, approached through a rose garden, where the busts of Shakespeare, Victor Hugo, and Cervantes overlooked the poet as he worked." (272)

{ 7 }

"What do I do, sir? I go for walks in the woods, through brambles which pull at my sleeves; I walk round my garden under the arching branches; I walk round my house on a wooden balcony. When the hot peppers have made me thirsty, I drink cool water straight from the jug. When time wipes out the white road, I listen to the evening, filled with anglers' bells, cowbells and barking. What do I do? Sometimes I walk a league to see whether the [River] Nive is a deeper blue further on; I come back along the bank...and that's all, if it's fine! If it rains, I drum on the window, or read, scribbling things in the margin; I dream or I work." — Rostand, about his country home, Cambo

{ 6 }

"Blackbird is interesting in that Chantecler shows a sort of favoritism toward him, who is more intelligent than the other animals, but he learns in a warped way. The Blackbird is shrewd to the public, popular viewpoints - calling himself a type of Parisian sparrow who uses slang-hip words and chic - not because they are true, but because they are new. This is the "two scourges which are the saddest in the world: the remark which always has to be a witty remark, and the beauty which has to be the latest fashion." (225)

{ 5 }

"Like Victor Hugo, whom he admired, Rostand wanted to reach ordinary people with his work, people who would understand his poetry with their hearts and not their intellects. So Edmond and Rosemonde lived a quiet life together away from the spite, gossip, and snobbery that characterized literary Paris." (61)

{ 4 }

"Cyrano would be Rostand's most successful hero yet: a poet, of course, idealistic, courageous, a man of deep feelings, his bravado an attempt to foil pity for his appearance, his wit a cover for his suffering heart." (132)

{ 3 }

"It is a pleasure to kill yourself for a work like that."

— Actor Benoît-Constant Coquelin, who played Cyrano, after 40+ curtain calls on opening night

{ 2 }

"The Twentieth Century has arrived." — Rostand, upon hearing the first word of the first play of 1900 in Paris: "Merde!"

{ 1 }

"A marvellous child whose soul is full of stars..." — Rostand, describing Victor Hugo after seeing his play Hernani

"My son, my dear son, when you become a man and read these verses where I name you, trembling, remember that your life had a rosy morning, a bright dawn, and think of those whose fate is painful, dark, and sad right from their birth; who never had a dawn, and never knew but shade, remember these are your brothers — go towards them." — Eugene Rostand, Edmond's father

{ 9 }

"What outward elegance remained [in 19th Century France] was only for show, masking grossness and lack of true feeling. In matters of the heart, courtesy and chivalry were made to seem ridiculous, and women were no longer accorded special respect. Rostand believed that even the French language had deteriorated from "the beautiful, pure, rather ceremonious, language of former times." There was more to Edmond's distaste for the materialism of his times than a simple nostalgia for a lost golden age. His attitude was positive, not negative. He was inspired his love of poetry to yearn for a life transformed by idealism, just as everyday things are transformed by the power of the...sun." (38)

{ 8 }

"Rostand's garden at Arnaga was as much an artistic creation as his house and his plays. He had taken great pleasure in designing it, and was forever thinking of new ways to improve it. The formal garden now ran the full length of the plateau, stretching away . towards the distant mountains, with its geometrical parterres full of vivid flowers, its lawns and pools and fountains, the whole framed by full-grown trees. Facing the classical orangery across the formal garden was a green arbour, approached through a rose garden, where the busts of Shakespeare, Victor Hugo, and Cervantes overlooked the poet as he worked." (272)

{ 7 }

"What do I do, sir? I go for walks in the woods, through brambles which pull at my sleeves; I walk round my garden under the arching branches; I walk round my house on a wooden balcony. When the hot peppers have made me thirsty, I drink cool water straight from the jug. When time wipes out the white road, I listen to the evening, filled with anglers' bells, cowbells and barking. What do I do? Sometimes I walk a league to see whether the [River] Nive is a deeper blue further on; I come back along the bank...and that's all, if it's fine! If it rains, I drum on the window, or read, scribbling things in the margin; I dream or I work." — Rostand, about his country home, Cambo

{ 6 }

"Blackbird is interesting in that Chantecler shows a sort of favoritism toward him, who is more intelligent than the other animals, but he learns in a warped way. The Blackbird is shrewd to the public, popular viewpoints - calling himself a type of Parisian sparrow who uses slang-hip words and chic - not because they are true, but because they are new. This is the "two scourges which are the saddest in the world: the remark which always has to be a witty remark, and the beauty which has to be the latest fashion." (225)

{ 5 }

"Like Victor Hugo, whom he admired, Rostand wanted to reach ordinary people with his work, people who would understand his poetry with their hearts and not their intellects. So Edmond and Rosemonde lived a quiet life together away from the spite, gossip, and snobbery that characterized literary Paris." (61)

{ 4 }

"Cyrano would be Rostand's most successful hero yet: a poet, of course, idealistic, courageous, a man of deep feelings, his bravado an attempt to foil pity for his appearance, his wit a cover for his suffering heart." (132)

{ 3 }

"It is a pleasure to kill yourself for a work like that."

— Actor Benoît-Constant Coquelin, who played Cyrano, after 40+ curtain calls on opening night

{ 2 }

"The Twentieth Century has arrived." — Rostand, upon hearing the first word of the first play of 1900 in Paris: "Merde!"

{ 1 }

"A marvellous child whose soul is full of stars..." — Rostand, describing Victor Hugo after seeing his play Hernani

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

{ * } Cyrano de Bergerac & 7 Other Great Plays

{ * } Chantecler by Rostand

{ * } The Princess Far-Away by Rostand

{ * } The Eaglet by Rostand

{ * } The Republic of Imagination by Azar Nafisi

{ * } Chantecler by Rostand

{ * } The Princess Far-Away by Rostand

{ * } The Eaglet by Rostand

{ * } The Republic of Imagination by Azar Nafisi