| "As long as through the working of laws and customs there exists a damnation by society, artificially creating hells in the very midst of civilization and complicating destiny, which is divine, with the man-made fate; as long as the three problems of the century are not resolved, the debasement of men by the proletariat, the moral degradation of women through hunger, and the stunting of children by keeping them in darkness; as long as in certain strata social suffocation is possible; in other words, and form an even broader perspective, as long as there are ignorance and misery on earth, books such as this one may not be without utility." — Victor Hugo on Les Misérables, 1862 |

A man sentenced to ten years of hard labor for stealing a crust of bread. A police detective devoted to upholding his brand of merciless justice. An unemployed mother choked by poverty into prostitution. An orphan girl exploited by her adoptive parents in order to further their thievery. A bereft revolutionary taking up his post on the barricades. And the man who wrote them all.

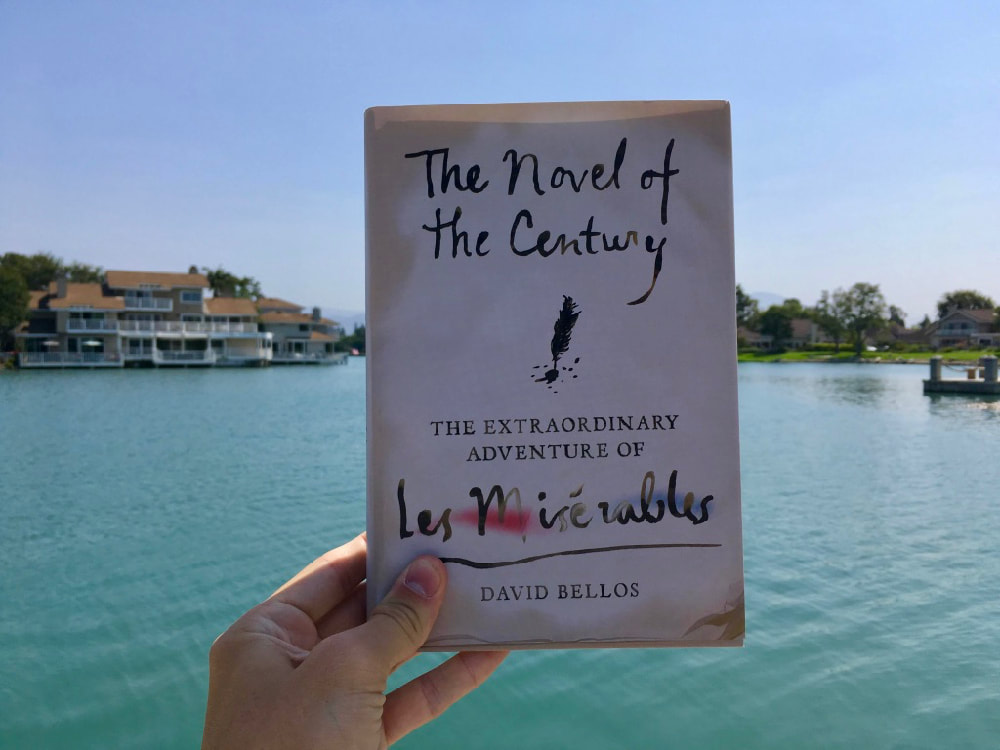

"From the day of its publication on 4 April 1862," author David Bellos writes, "Les Misérables has remained at the forefront of bestseller lists the world over. It has been read in French and in hundreds of translations by millions of people in any country you care to name. It was turned into a play within weeks and has been adapted for radio and the cinema screen over the last century and a half more than any other literary work. But the unique adventure of Les Misérables as a global cultural resource did not come about by chance. From his roof terrace with its wonderful view of Sark and the Sea, Victor Hugo always intended his great work to speak far beyond the borders of France, and beyond the pages of a book." It seems fitting that upon finishing The Novel of the Century: The Extraordinary Adventures of Les Miserables, I had amassed the most notes I've ever taken on a book: 22 full pages front and back.

The book's historical breadth and depth is astounding and built for readers both familiar or new to Les Miserables. Mirroring its subject's own structure, Novel is organized into five Parts with an Introduction, four Interludes, and Epilogue. We begin with Hugo, "open[ing] his eyes" to certain injustices around him and recorded in a journal titled, "Choses Vues" ("Things Seen"):

"I do not like these symptoms," Hugo wrote in 1847. "When there's poison in the blood...a mere graze can lead to an amputated limb." These observations and others (like the inhumanity of Parisian jails) would find themselves lifted, reworked, dramatized, published, and eventually devoured by adoring fans fifteen years later.

Bellos' book is a biography of a book, and I loved how he dipped into the bio of its author— but only in order to chart and traverse his greatest work's creation and publication. This might sound obvious, but it's one thing I wish Walter Isaacson had done much more in his bestselling biography on Steve Jobs. Granted the later is a biography about a man's life, but there are so many opportunities for a researcher to psychologize about Hugo from his personal life events. I didn't detect any of that. Hugo's public scandals, bohemian lifestyle, and ardent political views are handled with care, nuance, sympathy, and filtered for relevancy in an extremely refreshing way. Biographers, take note!

Moreover, Bellos' brevity is impressive. The one hundred plus sources consulted and referenced in Novel are at the author's disposal to pluck from and patch together with grand, Hugo-esque brushstrokes. Just one example of such contrast and condensation comes mid-way in which Bellos introduces Alexandre Dumas, a (turns out) fair-weather friend of Hugo's and the author of The Count of Monte Cristo, another 19th century adventure novel rivaling Les Misérables' own 1,400+ page count. Bellos' writes, "The Count of Monte Cristo is a story of extravagant and spectacular revenge, but Les Miserables asks us to be kind."

And asking us to be kind paid. Les Misérables was the largest book deal in history and it sold out for months, an instant bestseller in France and Belgium (Hugo's adoptive country until Napoleon II was no more). Soon Europe had her translations, and then, the US too—and the Confederacy. With the American Civil War raging, Robert E. Lee's army altered Les Misérables to Lee's Miserables, summoning Valjean's spirit, (mistakingly), often re-enacting and reading scenes from the novel between battles. In these ways, Jean Valjean's epic underdog story of redemption was a story for the world--the story of the 19th century. It was a novel of significant importance in the 20th too, from red Moscow to Washington, D.C.

Hugo said in his time, "I do not know whether [my book] will be read by all, but I wrote it for everyone. It speaks to England as much as to Spain, to Italy as much as to France, to Germany as much as to Iceland, to republics with slaves as well as to empires with serfs. Social problems go beyond borders. The sores of the human race, these running sores that cover the globe, don't stop at read or blue lines drawn on the map. Wherever men are ignorant and desperate, wherever women sell themselves for bread, wherever children suffer for want of instruction or a warm hearth, Les Misérables knocks on the door and says, 'Open up, I have come for you.'"

It's still a novel of the 21st century. And its creation is one extraordinary adventure. [JG]

"From the day of its publication on 4 April 1862," author David Bellos writes, "Les Misérables has remained at the forefront of bestseller lists the world over. It has been read in French and in hundreds of translations by millions of people in any country you care to name. It was turned into a play within weeks and has been adapted for radio and the cinema screen over the last century and a half more than any other literary work. But the unique adventure of Les Misérables as a global cultural resource did not come about by chance. From his roof terrace with its wonderful view of Sark and the Sea, Victor Hugo always intended his great work to speak far beyond the borders of France, and beyond the pages of a book." It seems fitting that upon finishing The Novel of the Century: The Extraordinary Adventures of Les Miserables, I had amassed the most notes I've ever taken on a book: 22 full pages front and back.

The book's historical breadth and depth is astounding and built for readers both familiar or new to Les Miserables. Mirroring its subject's own structure, Novel is organized into five Parts with an Introduction, four Interludes, and Epilogue. We begin with Hugo, "open[ing] his eyes" to certain injustices around him and recorded in a journal titled, "Choses Vues" ("Things Seen"):

- A man arrested for stealing a loaf of blackened, tough bread

- A girl, victim of a well-aimed snowball, fall on top an aristocrat and then dragged off to jail (during which Hugo interceded.)

- A street riot erupt over pay between employers and employees

"I do not like these symptoms," Hugo wrote in 1847. "When there's poison in the blood...a mere graze can lead to an amputated limb." These observations and others (like the inhumanity of Parisian jails) would find themselves lifted, reworked, dramatized, published, and eventually devoured by adoring fans fifteen years later.

Bellos' book is a biography of a book, and I loved how he dipped into the bio of its author— but only in order to chart and traverse his greatest work's creation and publication. This might sound obvious, but it's one thing I wish Walter Isaacson had done much more in his bestselling biography on Steve Jobs. Granted the later is a biography about a man's life, but there are so many opportunities for a researcher to psychologize about Hugo from his personal life events. I didn't detect any of that. Hugo's public scandals, bohemian lifestyle, and ardent political views are handled with care, nuance, sympathy, and filtered for relevancy in an extremely refreshing way. Biographers, take note!

Moreover, Bellos' brevity is impressive. The one hundred plus sources consulted and referenced in Novel are at the author's disposal to pluck from and patch together with grand, Hugo-esque brushstrokes. Just one example of such contrast and condensation comes mid-way in which Bellos introduces Alexandre Dumas, a (turns out) fair-weather friend of Hugo's and the author of The Count of Monte Cristo, another 19th century adventure novel rivaling Les Misérables' own 1,400+ page count. Bellos' writes, "The Count of Monte Cristo is a story of extravagant and spectacular revenge, but Les Miserables asks us to be kind."

And asking us to be kind paid. Les Misérables was the largest book deal in history and it sold out for months, an instant bestseller in France and Belgium (Hugo's adoptive country until Napoleon II was no more). Soon Europe had her translations, and then, the US too—and the Confederacy. With the American Civil War raging, Robert E. Lee's army altered Les Misérables to Lee's Miserables, summoning Valjean's spirit, (mistakingly), often re-enacting and reading scenes from the novel between battles. In these ways, Jean Valjean's epic underdog story of redemption was a story for the world--the story of the 19th century. It was a novel of significant importance in the 20th too, from red Moscow to Washington, D.C.

Hugo said in his time, "I do not know whether [my book] will be read by all, but I wrote it for everyone. It speaks to England as much as to Spain, to Italy as much as to France, to Germany as much as to Iceland, to republics with slaves as well as to empires with serfs. Social problems go beyond borders. The sores of the human race, these running sores that cover the globe, don't stop at read or blue lines drawn on the map. Wherever men are ignorant and desperate, wherever women sell themselves for bread, wherever children suffer for want of instruction or a warm hearth, Les Misérables knocks on the door and says, 'Open up, I have come for you.'"

It's still a novel of the 21st century. And its creation is one extraordinary adventure. [JG]

ABOUT DAVID BELLOS

| David Bellos teaches French and comparative literature at Princeton University. He is the author of three other books including Is That a Fish in Your Ear?, an "irreverent" study of translation that was nominated for the Los Angles times Book Prize in 2011. Dr. Bellos has a few excellent lectures and presentations on YouTube. I particularly enjoyed this one on the importance of translation on our own lives. |

| "Les Misérables expresses the beliefs that Hugo held, which were quite particular to him. He was never reluctant to say that he believed in God, but he did not subscribe to any established tradition or cult. Contrary to the impression that Les Misérables may make on some readers, Hugo was not a catholic: unlike most French people of his age, he had never been baptized or confirmed and never went into church to pray. But pray he did. And he was adamant that Les Misérables was "a religious book.' " – David Bellos, The Novel of the Century |

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

| NINETY-THREE | ROMANTICS |

| PERENNIAL SELLER Ryan Holiday | PAPER: PAGING THROUGH HISTORY Mark Kurlansky |