“When you said to me, “Tell me the story of your life,” I was not eager to begin. But when you added, “What I care most about is learning your reasons for loving life,” then I became eager, for that was a real subject.” — Jacques Lusseyran

INTO DARKNESS

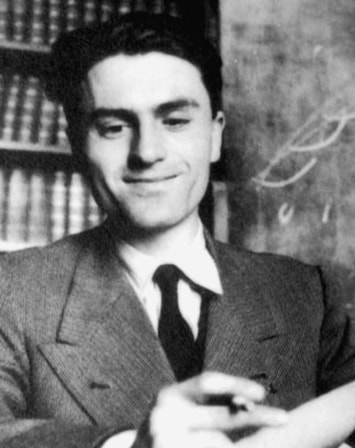

Jacques Lusseyran was blinded at the age of seven.

It happened one day at school in 1916. A fellow schoolboy accidentally shoved into little Jacques from behind in the hallway, smashing his face against the wall. The boy's eyeglasses shattering, and despite surgeries and time to heal, Lusseyran's vision was gone forever. From that day on though, he discovered a new world amidst the darkness.

"I remember well when I first arrived at the beach two months after the accident. It was evening and there was nothing there but the sea and its voice, precise beyond the power to imagine it," Lusseyran writes. "...It spoke to me in layers all at once. The waves were arranged in steps, and together they made one music, though what they said was different in each voice. There was rasping in the bass and bubbling in the top register. I didn't need to be told about the things that eyes could see...what the waves said they said twice over."

It happened one day at school in 1916. A fellow schoolboy accidentally shoved into little Jacques from behind in the hallway, smashing his face against the wall. The boy's eyeglasses shattering, and despite surgeries and time to heal, Lusseyran's vision was gone forever. From that day on though, he discovered a new world amidst the darkness.

"I remember well when I first arrived at the beach two months after the accident. It was evening and there was nothing there but the sea and its voice, precise beyond the power to imagine it," Lusseyran writes. "...It spoke to me in layers all at once. The waves were arranged in steps, and together they made one music, though what they said was different in each voice. There was rasping in the bass and bubbling in the top register. I didn't need to be told about the things that eyes could see...what the waves said they said twice over."

A NEW SIGHT

This new, deeper connection to reality was something he swiftly did not only accept, but even became glad of; Lusseyran's senses of touch, smell, and hearing became heightened. "I didn't even know whether I was touching [the apple] or it was touching me. As I became part of the apple, the apple became part of me...To put it differently, this means an end of living in front of things and a beginning of living with them."

In just six weeks, with the help of his mother, he learned Braille by reading the adventures of Mowgli in The Jungle Book. She also bought him a specially designed typewriter from Switzerland. But his new blindness, of course, was painfully isolating—and tempting. His dark inner world became a kind of "drug," but he grew weary of the temptation to always live internally and not experience reality. One way to combat this temptation was to walk the streets of Paris and the countryside. Through hours and days and weeks of trial and error, Lusseyran mapped much of it. He recovered in his parents quiet, clean, empty, safe storeroom if he ever became too disoriented from the work.

From his darkness, not only did young Jacques map the city, but also the hearts and minds of the strangers, teachers, parents, and friends he encountered. "People were not at all as they were said to be, and never the same for more than two minutes at a stretch." He recounts the "smell" of social obligations at school and church. "Just think how much suppressed anger, humiliated independence, frustrated vagrancy, and impotent curiosity can be accumulated by forty boys between the ages of ten to fourteen. So that was the source of the unpleasant odor and the smoke, which, for me, was like a physical presence..."

But his friends—especially Jean—were different. "We were still two, joyfully and freely two, so much that each of us lived twice every day. What bound us together was not just friendship, it was a religion."

In just six weeks, with the help of his mother, he learned Braille by reading the adventures of Mowgli in The Jungle Book. She also bought him a specially designed typewriter from Switzerland. But his new blindness, of course, was painfully isolating—and tempting. His dark inner world became a kind of "drug," but he grew weary of the temptation to always live internally and not experience reality. One way to combat this temptation was to walk the streets of Paris and the countryside. Through hours and days and weeks of trial and error, Lusseyran mapped much of it. He recovered in his parents quiet, clean, empty, safe storeroom if he ever became too disoriented from the work.

From his darkness, not only did young Jacques map the city, but also the hearts and minds of the strangers, teachers, parents, and friends he encountered. "People were not at all as they were said to be, and never the same for more than two minutes at a stretch." He recounts the "smell" of social obligations at school and church. "Just think how much suppressed anger, humiliated independence, frustrated vagrancy, and impotent curiosity can be accumulated by forty boys between the ages of ten to fourteen. So that was the source of the unpleasant odor and the smoke, which, for me, was like a physical presence..."

But his friends—especially Jean—were different. "We were still two, joyfully and freely two, so much that each of us lived twice every day. What bound us together was not just friendship, it was a religion."

THE INVASION

History marks May 1940 as when the Germans invaded France. But Jacques felt the invasion years earlier in 1934, when he was just thirteen, as he listened to the radio. He knew they would come, and looming closer to home was the reminder of his blindness by way of Jean and his boy friends who had discovered girls. "I told myself stories of boundaries that could never be crossed," but "I ridiculed my childhood dreams," Lusseyran writes. He was aware that those childhood days of "double, triple, countless, and forever new" were gone.

On June 14th, 1940, Nazi tanks entered a nearly deserted Paris. Jacques was just nineteen. Many French citizens adapted to the new reality, even allying with their conquerors. "Paris under the Occupation looked to me as if she were praying. She seems to be calling on someone, but hers was a voiceless cry."

But some would give her a voice.

On June 14th, 1940, Nazi tanks entered a nearly deserted Paris. Jacques was just nineteen. Many French citizens adapted to the new reality, even allying with their conquerors. "Paris under the Occupation looked to me as if she were praying. She seems to be calling on someone, but hers was a voiceless cry."

But some would give her a voice.

THE RESISTANCE

97% of the French resistance were men. 3% women. The majority were under 30 years old. 14% were under 18. There were different levels of resistance—violence, sabotage, financial support, logistical support (like bicycling weapons beneath greens to escape detection). Emerging from the resistance effort were young heroes who have since become immortalized.

Guy Moquet was a young man executed randomly at the hands of the Germans, and whose letters of courage emboldened his generation. Maroussia Naitchenko was a political activist adept at sensing and escaping Gestapo traps. The "sudden courage" that thousands of young men and women felt to resist the Nazi invaders was staggering. Their work included sabotaging Nazi supply lines and radio communications, hiding Jews and other refugees, assassinating officers and guards, stealing weapon caches, and helping Allied forces in 1944 onward. But, as Lusseyran recounts, "A country in disaster is swarming with traitors," and so secrecy and loyalty were paramount.

Lusseyran was voted by his teenage comrades in the resistance to be in charge of all recruiting, because he had "the sense of human beings." During the resistance, Lusseyran interviewed 600+ potential recruits. "People would not easily deceive me. I should not forget names or places, addresses, or telephone numbers." Always before joining the resistance, candidates were told, "Go to the blind man. When he has seen you, I shall have something to tell you." French jazz clubs, a.k.a. 'Zazous,' were a popular recruiting location. During the war, Lusseyran helped build one of the largest underground networks in France.

Guy Moquet was a young man executed randomly at the hands of the Germans, and whose letters of courage emboldened his generation. Maroussia Naitchenko was a political activist adept at sensing and escaping Gestapo traps. The "sudden courage" that thousands of young men and women felt to resist the Nazi invaders was staggering. Their work included sabotaging Nazi supply lines and radio communications, hiding Jews and other refugees, assassinating officers and guards, stealing weapon caches, and helping Allied forces in 1944 onward. But, as Lusseyran recounts, "A country in disaster is swarming with traitors," and so secrecy and loyalty were paramount.

Lusseyran was voted by his teenage comrades in the resistance to be in charge of all recruiting, because he had "the sense of human beings." During the resistance, Lusseyran interviewed 600+ potential recruits. "People would not easily deceive me. I should not forget names or places, addresses, or telephone numbers." Always before joining the resistance, candidates were told, "Go to the blind man. When he has seen you, I shall have something to tell you." French jazz clubs, a.k.a. 'Zazous,' were a popular recruiting location. During the war, Lusseyran helped build one of the largest underground networks in France.

BUCHENWALD

Lusseyran was eventually arrested, betrayed by a young spy. The Nazi SS arrested him and interrogated him 38 times. They had compiled a 50-page report on his travels and activities, which they had been tracking for weeks. He declared his innocence, and, lying "twenty times per minute," managed to keep his stories in order. Still, they jailed him for six months.

"In prison, more than ever before, it is within yourself that you must live. If there is a person you cannot do without, not possibly—for instance a girl somewhere outside the walls—do as I did then. Look at her several times a day for long time...And for a long time you will not even realize you are in prison."

Eventually though, the Nazis transported Lusseyran and 2,000 frenchman to Buchenwald. There he stayed for fifteen months. When the American's liberated the concentration camp under General Patton, only thirty of those Frenchman had survived. Jacques was one of them. During the war, 380,000 men had been killed at Buchenwald alone. Jacques best friend, Jean, died of starvation the day before reaching Jacques on a train from another prison.

"In prison, more than ever before, it is within yourself that you must live. If there is a person you cannot do without, not possibly—for instance a girl somewhere outside the walls—do as I did then. Look at her several times a day for long time...And for a long time you will not even realize you are in prison."

Eventually though, the Nazis transported Lusseyran and 2,000 frenchman to Buchenwald. There he stayed for fifteen months. When the American's liberated the concentration camp under General Patton, only thirty of those Frenchman had survived. Jacques was one of them. During the war, 380,000 men had been killed at Buchenwald alone. Jacques best friend, Jean, died of starvation the day before reaching Jacques on a train from another prison.

LIGHT

Lusseyran's memoir ends abruptly after recounting the war. He catalogs the first 20 years of his life, which he believes belongs to the world—especially America, to whom he is a "guest" and lived in for time as a professor. He closes his book with two truths:

1. "Joy does not come from outside, for whatever happens to us it is within."

2. Light does not come to us from without. Light is in us, even if we have no eyes." [JG]

1. "Joy does not come from outside, for whatever happens to us it is within."

2. Light does not come to us from without. Light is in us, even if we have no eyes." [JG]

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jacques Lusseyran ((1924-1971) was blinded at age seven, formed a French Resistance group at age seventeen, and endured fifteen months at Buchenwald. After World War II, he became a professor in the United States at Case Western Reserve University.

He wrote one other work in his lifetime, Against the Pollution of the I, a collection of six essays that chronicle the heroism at Buchenwald by fellow inmates and experiences with his inner vision throughout this life.

He wrote one other work in his lifetime, Against the Pollution of the I, a collection of six essays that chronicle the heroism at Buchenwald by fellow inmates and experiences with his inner vision throughout this life.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE