Dear Friends and Readers:

2023 was an incredible journey on and off the page for me. I traveled more than ever (San Francisco, Austin, Palm Springs, Hawaii, Germany, Netherlands, and the country of Georgia). And I also managed to make it one of the most productive reading and writing years ever.

Per tradition, I've rounded up my absolute ten favorite reads from 2023 plus fifteen others that I whole-heartedly enjoyed. Whether you pick up one or ten of these books, fiction or non-fiction, now or in the future, I hope that they give you as much as they have given me.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year,

Jon

P.S. Here are my yearly roundups from 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, and 2015.

P.P.S. You can subscribe to the Reading List for more. Each month, I'll email you 3-6 books that I absolutely couldn't put down—usually a mix of fiction and nonfiction. I try to steer clear of bestseller (fake) lists, and instead explore authors who challenge my worldview, enchant me through language, and model how to live more nobly.

2023 was an incredible journey on and off the page for me. I traveled more than ever (San Francisco, Austin, Palm Springs, Hawaii, Germany, Netherlands, and the country of Georgia). And I also managed to make it one of the most productive reading and writing years ever.

Per tradition, I've rounded up my absolute ten favorite reads from 2023 plus fifteen others that I whole-heartedly enjoyed. Whether you pick up one or ten of these books, fiction or non-fiction, now or in the future, I hope that they give you as much as they have given me.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year,

Jon

P.S. Here are my yearly roundups from 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, and 2015.

P.P.S. You can subscribe to the Reading List for more. Each month, I'll email you 3-6 books that I absolutely couldn't put down—usually a mix of fiction and nonfiction. I try to steer clear of bestseller (fake) lists, and instead explore authors who challenge my worldview, enchant me through language, and model how to live more nobly.

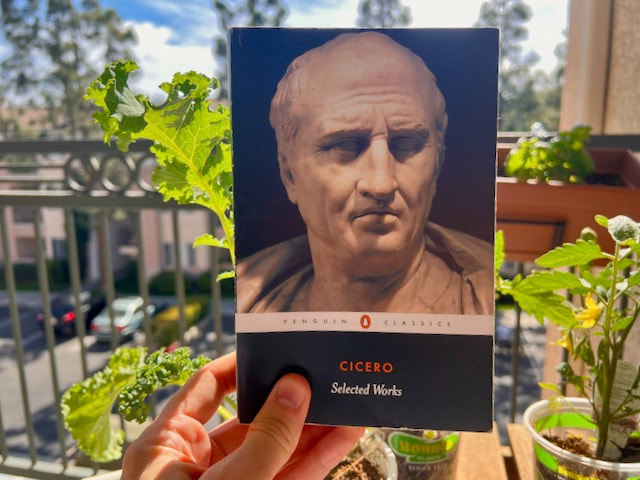

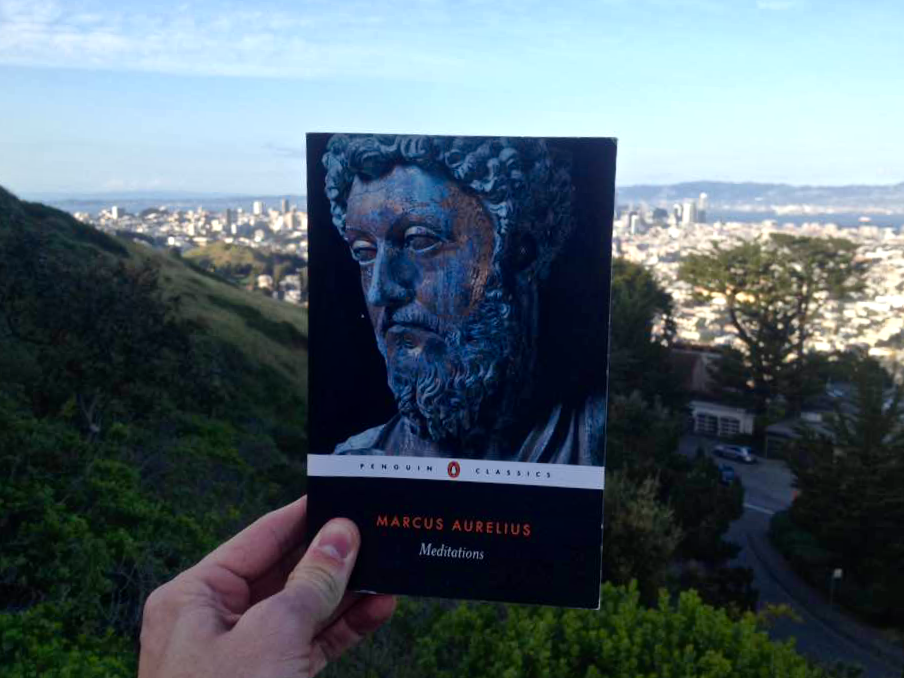

10. THAT ONE SHOULD DISDAIN HARDSHIPS, LETTERS FROM A STOIC, AND MEDITATIONS

The One Should Disdain From Hardships: This is a compilation of the 21 surviving discourses of the stoic philosopher, Gaius Musonius Rufus (30-101 CE). He was the teacher of my favorite stoic, Epictetus, and widely influential in imperial Rome during his lifetime. In fact, fearing Rufus' influence and sympathies for the senate, Nero banished the teacher and many other philosophers between 71 and 75 CE. Rather than decrying the injustice, Rufus writes that it was an opportunity to practice philosophy and live a simple, honest life in his new home, the arid island of Gyaros. He eventually returned to Rome after Nero's death to resume teaching and study. These eight discourses spoke strongest to me:

Letters From a Stoic: This is a compilation of some of the 124 private letters and treatises written by Lucius Annaeus Seneca. Born in Cordoba, (Roman) Spain to an accomplished lawyer and rhetorician, Seneca the Younger as he is known was a kind of proto-renaissance man of the Roman empire. He was raised in Egypt where he learned business administration, finances, geography, and ethnology. Later he delved into studying marine life, meteorology, and Pythagorean mysticism—which eventually led him to stoic philosophy. Seneca was the teacher of young Emperor Nero, a playwright of tragedies, and widely regarded for centuries after as a master of writing during 'the silver age of Latin'.

As I reread Letters this fall, I was reminded of the poet Archilochus' most-famous line: "The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing." Seneca is the fox. His letters are chock-full of interesting observations on daily life and himself like:

And yet, he struggled to live up to his own advice. Angry outbursts, lustful affairs, gossip within the Roman corridors of power, and, eventually plots to usurp that power—Seneca's shortcomings led to his suicide in 65 CE — falling on his own sword to save his wife and sons from the wrath of Emperor Nero, his own creation.

Meditations: These are the private writings of perhaps the greatest Roman Emperor, Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE). Dying from disease on the empire's northern frontier in late winter, the Emperor had actually ordered his servant to burn it. But thankfully, the servant whose name is long lost to history, disobeyed. Meditations' twelve books (chapters) are filled with both a ruthless self-examination and an earnest attempt to square the people, events, and conflicts around him. And his insights and wisdom have procured a citizenry across the globe: from Thomas Jefferson to American soldiers in the jungles of Vietnam.

I read Meditations for the first time in 2012 when I had just graduated college and found myself in Irvine, California at my first 'grown-up' job. Rereading it eleven years later was both new and familiar. Some themes that stuck out to me this time was the orientation of philosophy as therapeutic—a tool to weather the storms of life, to extract beauty and value from every day encounters, and to better understand oneself.

I love that Aurelius opens Meditations with an outpour of gratitude for the people who helped him most in life: family, friends, teachers, and inspirational historical figures. The longest section in Book 1's gratitudes belong to his adoptive father, Antoninus Pius, then secondly, to the gods themselves.

You can read more of my thoughts on Meditations here.

- That Man is Born with an Inclination Toward Virtue

- That Women Too Should Study Philosophy

- That Exile is not an Evil

- What means of Livelihood is Appropriate for a Philosopher?

- What is the Chief End of Marriage

- Is Marriage a Handicap for the Pursuit of Philosophy?

- Must One Obey One's Parents under all Circumstances?

- On Furnishings

Letters From a Stoic: This is a compilation of some of the 124 private letters and treatises written by Lucius Annaeus Seneca. Born in Cordoba, (Roman) Spain to an accomplished lawyer and rhetorician, Seneca the Younger as he is known was a kind of proto-renaissance man of the Roman empire. He was raised in Egypt where he learned business administration, finances, geography, and ethnology. Later he delved into studying marine life, meteorology, and Pythagorean mysticism—which eventually led him to stoic philosophy. Seneca was the teacher of young Emperor Nero, a playwright of tragedies, and widely regarded for centuries after as a master of writing during 'the silver age of Latin'.

As I reread Letters this fall, I was reminded of the poet Archilochus' most-famous line: "The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing." Seneca is the fox. His letters are chock-full of interesting observations on daily life and himself like:

- How to not be defeated by people who annoy you (Seneca found Rome's street traffic and rowdy gym bros too much when he needed to work)

- The importance of learning over a lifetime to love yourself and others—not the utility they bring

- Viewing blushing as a sign of self-awareness which can lead to self-improvement; eventually wisdom

- How to age gracefully by strengthening one's moral constitution and behaving calmly with one's negative emotions in check (especially anger)

- The personal satisfaction and growth that comes from learning, especially philosophy, and the shame and ugliness that comes from a lack of reforming oneself

And yet, he struggled to live up to his own advice. Angry outbursts, lustful affairs, gossip within the Roman corridors of power, and, eventually plots to usurp that power—Seneca's shortcomings led to his suicide in 65 CE — falling on his own sword to save his wife and sons from the wrath of Emperor Nero, his own creation.

Meditations: These are the private writings of perhaps the greatest Roman Emperor, Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE). Dying from disease on the empire's northern frontier in late winter, the Emperor had actually ordered his servant to burn it. But thankfully, the servant whose name is long lost to history, disobeyed. Meditations' twelve books (chapters) are filled with both a ruthless self-examination and an earnest attempt to square the people, events, and conflicts around him. And his insights and wisdom have procured a citizenry across the globe: from Thomas Jefferson to American soldiers in the jungles of Vietnam.

I read Meditations for the first time in 2012 when I had just graduated college and found myself in Irvine, California at my first 'grown-up' job. Rereading it eleven years later was both new and familiar. Some themes that stuck out to me this time was the orientation of philosophy as therapeutic—a tool to weather the storms of life, to extract beauty and value from every day encounters, and to better understand oneself.

I love that Aurelius opens Meditations with an outpour of gratitude for the people who helped him most in life: family, friends, teachers, and inspirational historical figures. The longest section in Book 1's gratitudes belong to his adoptive father, Antoninus Pius, then secondly, to the gods themselves.

You can read more of my thoughts on Meditations here.

9. TRACTION: HOW ANY STARTUP CAN ACHIEVE EXPLOSIVE CUSTOMER GROWTH

This is a highly valuable business book that has personally helped me to scale two e-commerce clients in 2023. The goal of the book is to provide a fast, cheap, and valueable process that businesses can replicate to find traction, or as the authors describe it, "quantitative evidence of customer demand."

Two patterns of struggling business growth teams are: 1. an over-reliance on existing historical channel(s) and 2. a difficulty in predicting which of the 19 known channels will work best for their own business.

Enter the Bullseye approach. Below are two explanation slides and 3 example slides for channel ideas:

Two patterns of struggling business growth teams are: 1. an over-reliance on existing historical channel(s) and 2. a difficulty in predicting which of the 19 known channels will work best for their own business.

Enter the Bullseye approach. Below are two explanation slides and 3 example slides for channel ideas:

8. ROSEMARY'S BABY

Ira Levin is a treasure. He is one of the great forgotten authors of the twentieth century, along with Ayn Rand and Terence Rattigan—both of whom are referenced in Rosemary's Baby. Levin's style shines here with brevity, personality, and page-turning suspense. I could not put this one down, something I had experienced with his most-famous work, The Stepford Wives, a few years back.

His command of language is masterful, but easy to miss. He breaks and bends grammar to improve the story: (describing Rosemary and Guy's new apartment with "a high high ceiling", capitalizing "The Night Someone Was on The Fire Escape" to mark a strong memory between friends, describing a dog's tail motion as "wig-wagged"). Simple, forced perspective.

And such good suspense. I read the last hundred pages in one sitting. The ticking-time-bomb of the creepy, unholy situation felt so real—like it could be happening now, next door.

His command of language is masterful, but easy to miss. He breaks and bends grammar to improve the story: (describing Rosemary and Guy's new apartment with "a high high ceiling", capitalizing "The Night Someone Was on The Fire Escape" to mark a strong memory between friends, describing a dog's tail motion as "wig-wagged"). Simple, forced perspective.

And such good suspense. I read the last hundred pages in one sitting. The ticking-time-bomb of the creepy, unholy situation felt so real—like it could be happening now, next door.

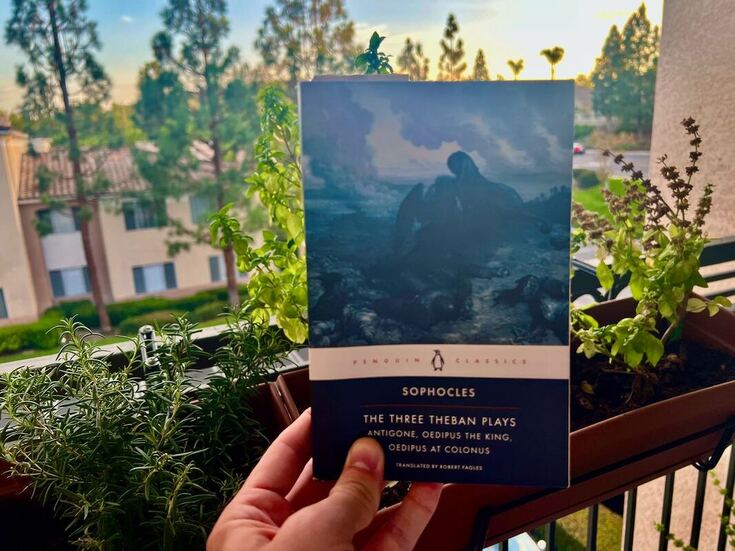

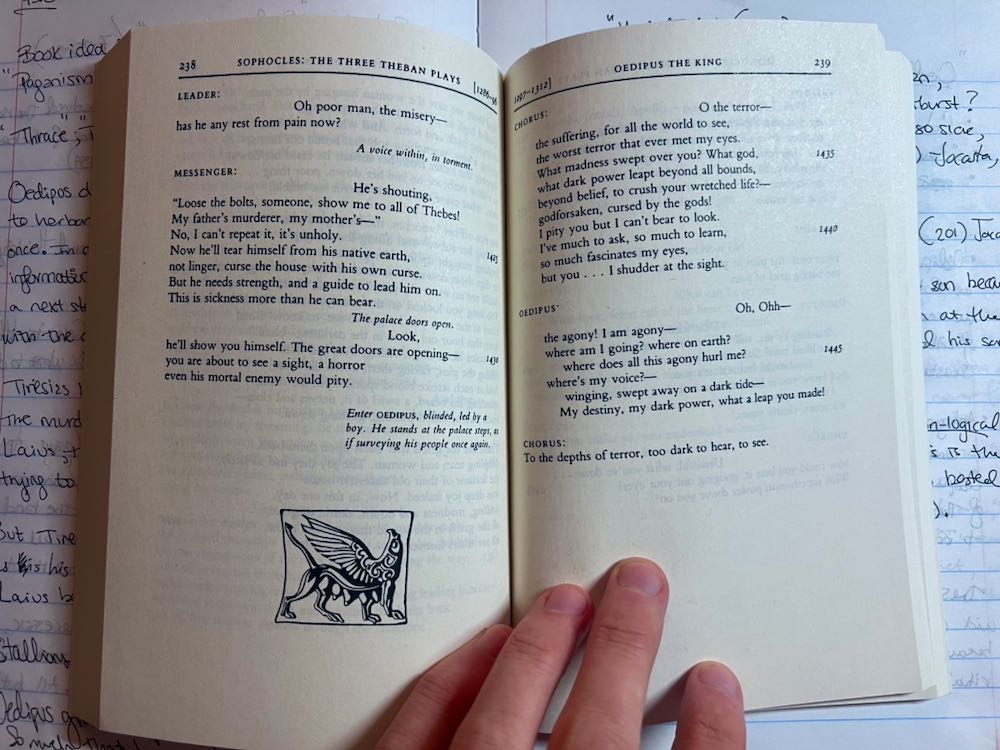

7. ANTIGONE

I first read Sophocles' play in the fall of my freshman year of high school. Antigone's defiance of the King (and her potential father-in-law) to honor the memory of her dead brother cut through so many forgettable assigned readings. It was her proud, heroic, and uncompromising actions in the face of great odds that made me love her—her decision to rise above a bully-king even if that means certain death. Fourteen years later, it was still such a powerful experience.

I also would highly recommend Sophocles' other two Theban Plays: Oedipus the King and Oedipus at Colonus, which I enjoyed in 2021 too. Aristotle believed the first to be the best work of literature at the time, greater ever than Homer's epic poems Iliad and the Odyssey.

I also would highly recommend Sophocles' other two Theban Plays: Oedipus the King and Oedipus at Colonus, which I enjoyed in 2021 too. Aristotle believed the first to be the best work of literature at the time, greater ever than Homer's epic poems Iliad and the Odyssey.

6. THE WRITINGS OF EPICURUS

“Stranger here you will do well-to-tarry; here our highest good is pleasure. The caretaker of that abode, a kindly host, will be ready for you; he will welcome you with bread, and serve you with water also in abundance, with these words: ‘Have you not been well entertained?’ This garden does not whet your appetite but quenches it.”

— Sign at the entrance of Epicurus' walled garden in Athens

— Sign at the entrance of Epicurus' walled garden in Athens

Epicurus (341–270 BCE) founded what became known as the Epicurean school of philosophy circa 307 BCE. It was known as The Garden in Athens, walled off and full of men, women, and even young ones from different classes, who gathered at a simple table for food, drink, and conversation. Epicurus held that physical and mental pleasure (and the absence of pain) is the highest good for a human. 'Ataraxia' (freedom from mental anguish) was the true source of happiness and what humans should strive toward.

Achieving ataraxia was difficult — namely because Epicurus thought humans were plagued by two great fears: death and judgement from the gods. And so his philosophy delves into cause and effect, free will, and cosmology (understanding what the universe is comprised of and how the system(s) work). Both atheism and atomism are central to Epicureanism, a system much deeper than the meme that later Christians constructed (a rabid, range-of-the-moment hedonist).

Interestingly, the Epicureans were considered the rival school to the Stoics (and to a lesser degree the Cynics), but Seneca and Marcus Aurelius both engage with Epicurus' ideas quite frequently in their surviving works. What I appreciated most was comparing the two schools with one another — and also Aristotle's own views on happiness. This year, I also read On the Nature of Things by Lucretius, a 7000-line poem written by a Roman follower of Epicurus.

Achieving ataraxia was difficult — namely because Epicurus thought humans were plagued by two great fears: death and judgement from the gods. And so his philosophy delves into cause and effect, free will, and cosmology (understanding what the universe is comprised of and how the system(s) work). Both atheism and atomism are central to Epicureanism, a system much deeper than the meme that later Christians constructed (a rabid, range-of-the-moment hedonist).

Interestingly, the Epicureans were considered the rival school to the Stoics (and to a lesser degree the Cynics), but Seneca and Marcus Aurelius both engage with Epicurus' ideas quite frequently in their surviving works. What I appreciated most was comparing the two schools with one another — and also Aristotle's own views on happiness. This year, I also read On the Nature of Things by Lucretius, a 7000-line poem written by a Roman follower of Epicurus.

5. THE HARRY POTTER SERIES

by J.K. Rowling (especially The Order of the Phoenix)

There are quite a few book series from my childhood that fostered a lifelong love for reading. Harry Potter is certainly among them. That's why in 2023 I made the year-long effort to work all seven books into my Audible listening list. Jim Dale, the award-winning narrator of the series did an exceptional job at voice-acting all of the characters. What struck me this time was how prescient the series was, particularly Books 4 and 5, which explore themes of fake news, government encroachment, self-censorship, and tribalism (mudbloods vs. pure bloods).

But amidst all of the dark plans and bad guys, shines a positive and good-natured cast of heroes, professors, friends, allies, and animal companions. I'm grateful to have revisited Hogwarts, Diagon Alley, Hogsmead, the Burrow, and Gringotts to feel like a kid again. I can't wait to do the same with the original Inheritance Cycle and Paolini's newly released Book 5.

But amidst all of the dark plans and bad guys, shines a positive and good-natured cast of heroes, professors, friends, allies, and animal companions. I'm grateful to have revisited Hogwarts, Diagon Alley, Hogsmead, the Burrow, and Gringotts to feel like a kid again. I can't wait to do the same with the original Inheritance Cycle and Paolini's newly released Book 5.

4. THE TWO TOWERS & THE RETURN OF THE KING

As I mentioned last year when I finished The Fellowship of the Ring, Tolkien's world-building is astounding. From Middle-Earth's geography, history, languages, and culture to the beloved fellowship of nine companions trying to save it, I could not wait to finish the trilogy. This summer I devoured the Audible versions of both The Two Towers and The Return of the King while living and working in Germany. Andy Serkis, who played Smeagol in the movies, narrates so well.

Later on in the fall, I also really enjoyed his renditions of The Silmarillion & The Hobbit.

Later on in the fall, I also really enjoyed his renditions of The Silmarillion & The Hobbit.

3. KING WARRIOR MAGICIAN LOVER

"In the late 20th century, we face a crisis in masculine identity of vast proportions...why is there so much gender confusion today, at least in the United States and Western Europe? ... We can look at family systems and see the breakdown of the traditional family...We have to look at two other factors...first, we need to take very seriously the disappearance of ritual processes for initiating boys into manhood...a second factor...show to us by one strain of feminist critique, is called patriarchy."

— Moore and Gillette, Introduction

— Moore and Gillette, Introduction

This is a book ahead of its time. Originally published in 1990, the authors explore the beginnings of a now-much-worse-now crisis in western culture. The (intentional) stunting of boys by restricting their maturation is systematic, the authors contend, but fixable. To become men, boys must first graduate from boy psychology to man psychology. In the past this had been done with a sacred space (devoid of females), a ritual elder (male; wise; mature), a death of the child's ego, and a successful completion of a painful task. But instead, there are only pseudo-initiations (prisons, military conscription, gangs) which wound and destroy, but do not nurture or generate growth.

Boys must be nurtured to grow on four planes of existence, each a side of an ever-stacking pyramid: the king (wise leadership), warrior (physical protector), magician (productive abilities), and lover (fostering healthy relationships). Initiation into manhood is a lifelong process, with clear steps in between and maturating is about exploring the outer reaches of our inner spaces.

If you enjoy Jordan Peterson's Twelve Rules for Life, the works of Carl Jung, Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, reading Greek myths, or maybe just want to get a healthier perspective on life than the garbage we're fed on social media, this one is for you.

Boys must be nurtured to grow on four planes of existence, each a side of an ever-stacking pyramid: the king (wise leadership), warrior (physical protector), magician (productive abilities), and lover (fostering healthy relationships). Initiation into manhood is a lifelong process, with clear steps in between and maturating is about exploring the outer reaches of our inner spaces.

If you enjoy Jordan Peterson's Twelve Rules for Life, the works of Carl Jung, Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, reading Greek myths, or maybe just want to get a healthier perspective on life than the garbage we're fed on social media, this one is for you.

2. ARISTOTLE'S WAY: HOW ANCIENT WISDOM CAN CHANGE YOUR LIFE

Aristotle of Stagiera (384—322 BCE) is perhaps still one of the most influential philosophers in the world. He was the student of Plato, the teacher of Alexander the Great, and the father of logic. His greatest love was actually studying the natural world, particularly animals. He adored most in art Sophocles, especially the first of his Theban Plays, Oedipus the King, because it showed humans with agency making moral decisions based off their reasoning mind. He lived a happy and productive life with best friends and a healthy family, and he successfully navigated political turmoil for himself and his homeland.

Edith Hall's book is a refreshing encapsulation of much of Aristotle's views on happiness ain order to help you achieve your own. President John F. Kennedy summed up Aristotelian happiness in a single sentence: "It means the full use of your powers along lines of excellence in a life affording scope." Happiness, Aristotle contends, comes as a result of good habits, which come from an effortful learning process. Your life is a project and requires active engagement with the world in order to improve it and yourself.

Organized into ten entertaining and educational chapters, I was really pleasantly surprised by this book and the author's ability to clarify Aristotle's views with modern examples. In particular I loved her chapters on Communication (rhetoric) Potential, Decisions, and Intentions (ethics), and the book's closing, which explores Aristotle's views on mortality.

You may also love Joe Sachs' translation of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, which I recommended last year.

Edith Hall's book is a refreshing encapsulation of much of Aristotle's views on happiness ain order to help you achieve your own. President John F. Kennedy summed up Aristotelian happiness in a single sentence: "It means the full use of your powers along lines of excellence in a life affording scope." Happiness, Aristotle contends, comes as a result of good habits, which come from an effortful learning process. Your life is a project and requires active engagement with the world in order to improve it and yourself.

Organized into ten entertaining and educational chapters, I was really pleasantly surprised by this book and the author's ability to clarify Aristotle's views with modern examples. In particular I loved her chapters on Communication (rhetoric) Potential, Decisions, and Intentions (ethics), and the book's closing, which explores Aristotle's views on mortality.

You may also love Joe Sachs' translation of Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics, which I recommended last year.

1. THE ANATOMY OF STORY

This book was crucial for me to restructure and revise a novel that I have been writing (and rewriting) for many years. Rather than getting mired down in Jungian archetypes and genre formulas (a common problem of writing reference books), The Anatomy of Story according to its author is aimed to pick up where Aristotle's Poetics left off. Truby unpacks story premises, plot structures, character development, moral themes, scene pacing and order, and style (especially dialogue). There are also eleven helpful exercises to complete at the end of each chapter, which I did for my own in-progress novel.

I plan to read Truby's sequel book, The Anatomy of Genre, in 2024.

I plan to read Truby's sequel book, The Anatomy of Genre, in 2024.

15 MORE BOOKS I ENJOYED

This year, like most years, I uncovered so many other enriching, thrilling, substantive stories. So, below are fifteen more. They were my hiking companions, sauna tag-alongs, and loooong-flight friends. Whether you pick up one or ten of them, from above or below, now or in the future, I hope that they give you as much to think about as they have given me.

1. The Complete Letters of Pliny the Younger. Pliny's letters paint a vivid account of Roman culture circa 80-100 CE. The praetor (Roman civil servant) under Domitian and later prefect under Trajan, explores Roman rituals and religion, the rise of early Christianity, the eruption of Vesuvius which killed his uncle, the social-political life in the capital, and visual descriptions of his beloved Tuscan estates. I particularly loved his description of a natural rhythmic spring located on the eastern side of Lake Como. The spring fills up and overflows every six to eight hours and it also fascinated Leonardo da Vinci.

2. The Describer's Dictionary by David Grambs. My screenwriting mentor recommended this in college and it was so useful to revisit. Grambs offers a well-organized dictionary to describe 'adjectively' (with modifiers). Inside are thousands of words, mostly unusual and unpopular (aslant; sundered; glacis; frith; sashaying; virile; wistful) and structured by topics and themes (colors, terrain, architecture, animals, etc.). Additionally, he includes dozens of passages from fiction and non-fiction works that showcase excellent word-choice ("Then I went out to the courtyard. The night was clear. The toothed roof-edge, the watchman with his spear and horn, stood black against the stars." — Mary Renault, "The King Must Die").

3. Penguin's compendium of Early Greek Philosophy. This is the origin story of Western thought, which begins—not in Athens—but on the eastern shore of the Aegean sea, in the Greek states of Ionia, specifically the city-state Miletus circa 585 B.C. when, legend has it, Thales predicted an eclipse of the sun on May 28th. Predating the great schools of Plato and Aristotle (400-100 BCE) and of Socrates' execution (399 BCE), the early Greek philosophers, or Pre-Socratics, mostly explored three topics: logic, ethics, and physics (nature). They saw the world as ordered, intelligible, likely created by gods whose powers were less than nature's, and that the systems in the world were beautiful and pleasant to contemplate. I loved reading the fragments of the Ionians and Eleatics, especially Zeno, Parmenides, Heraclitus, and Democritus.

4. The Selected Poetry of Li Po and Tu Fu. My friend, a very well-read individual, suggested I try some ancient Chinese poetry for its this-world, human-value perspective. I was grateful that I did. Li Po (701-62 CE) and Tu Fu (712-70 CE) were devoted friends and are traditionally considered the greatest of the Chinese poets. From Li Po's work, I sense a loner who wants to be found—not by his own words nor by others'—but by nature herself.

2. The Describer's Dictionary by David Grambs. My screenwriting mentor recommended this in college and it was so useful to revisit. Grambs offers a well-organized dictionary to describe 'adjectively' (with modifiers). Inside are thousands of words, mostly unusual and unpopular (aslant; sundered; glacis; frith; sashaying; virile; wistful) and structured by topics and themes (colors, terrain, architecture, animals, etc.). Additionally, he includes dozens of passages from fiction and non-fiction works that showcase excellent word-choice ("Then I went out to the courtyard. The night was clear. The toothed roof-edge, the watchman with his spear and horn, stood black against the stars." — Mary Renault, "The King Must Die").

3. Penguin's compendium of Early Greek Philosophy. This is the origin story of Western thought, which begins—not in Athens—but on the eastern shore of the Aegean sea, in the Greek states of Ionia, specifically the city-state Miletus circa 585 B.C. when, legend has it, Thales predicted an eclipse of the sun on May 28th. Predating the great schools of Plato and Aristotle (400-100 BCE) and of Socrates' execution (399 BCE), the early Greek philosophers, or Pre-Socratics, mostly explored three topics: logic, ethics, and physics (nature). They saw the world as ordered, intelligible, likely created by gods whose powers were less than nature's, and that the systems in the world were beautiful and pleasant to contemplate. I loved reading the fragments of the Ionians and Eleatics, especially Zeno, Parmenides, Heraclitus, and Democritus.

4. The Selected Poetry of Li Po and Tu Fu. My friend, a very well-read individual, suggested I try some ancient Chinese poetry for its this-world, human-value perspective. I was grateful that I did. Li Po (701-62 CE) and Tu Fu (712-70 CE) were devoted friends and are traditionally considered the greatest of the Chinese poets. From Li Po's work, I sense a loner who wants to be found—not by his own words nor by others'—but by nature herself.

Peach petals float their streams away in secret

To other skies and earths than those of mortals

5. Jason and the Golden Fleece by Apollonius of Rhodes. I had heard an excellent retelling of this myth a few years back by Stephen Fry, but I wanted to read it for myself—especially because it's set on the Black Sea, whose shores I traversed myself while reading it. While I didn't find "the shaded grove of Ares, where the fleece hangs on the top of an oak tree...guarded...by a watchful dragon..." it was a once-in-a-lifetime trip. Apollonius' descriptions of sunlight and water are spectacular, as is his characterization of Medea.

6. On the Nature of Things by Lucretius. This didactic poem is written in six parts circa 50 BCE by a Roman philosopher and poet. Within its 7000 lines, the author expounds upon Epicurus' school of philosophy from several hundred years earlier. Lucretius follows the Epicurean line of thinking that atoms comprise a godless universe and their nature determines much of the systems found in our world, including two crucial pursuits of humans—acquiring pleasures and minimizing pains. Two of the highest pleasures for Lucretius and Epicurus include friendship and contemplation (of life's big questions). I loved how Lucretius fused philosophical ideas with poetic forms.

7. The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Orczy. Paris, 1792. The Reign of Terror's guillotines are in full swing. Aristocrats are given no quarter by the lower classes, who also steal their fortunes. Enter the Scarlet Pimpernel, a disguised Englishman dead set on saving as many innocent French nobles as possible. The story is swashbuckling and quick-paced; I really appreciated Orczy's efficient characterization, which drives the plot forward to its climax.

8. 38 Fiction Writing Mistakes (and How to Avoid Them) by Jack M. Bickham. I picked this up at the recommendation of Dr. Leonard Peikoff a few years back. And despite the oh-so-1990s style cover, was pleasantly surprised by the advice. In particular, Mistake #22: Don't Ignore Scene Structure.

Anytime writing a scene you must:

A. Decide the main character's immediate goal

B. Get this clearly written down into the scene.

C. On a separate note, write down for yourself, clearly, briefly the scenic question. (Ex: Will the hero sink the battleship? It must have a yes/no answer.

D. In your story, after the goal has been shown, bring in another character who now states, just as clearly his opposition.

E. Plan the maneuvers and steps in the conflict between the two.

F. Write the scene moment by moment; no summary.

G. Devise the disastrous ending the scene — a reversal that answers the question with bad outcome from the protagonist's POV.

9. The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoevsky. Having read Crime and Punishment in high school but no other works by Dostoevsky, I was interested in giving another of his books a try. My understanding is that The Idiot was the author's attempt to depict an innocent man. In it, twenty-six-year-old Prince Myshkin returns to Russia from a mental hospital in Switzerland. Believing his mental breakdowns are behind him, he attempts to assimilate back into his cultural heritage, against others' ulterior motivations.

10 & 11. The Silmarillion & The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien. Upon finishing the LOTR trilogy with Andy Serkis, I eventually plowed on into Middle Earth's two other greatest tales. While I enjoyed aspects of The Silmarillion's myths and legends, my favorite part came in the beginning in which Tolkien recounts the creation-myth of his universe. It involves the existence of many eternal stars and eventually the birth of sentient beings who worshipped their light with their voices. Eventually these voices formed a heavenly chorus of melodies, which birthed new creations: water, earth, and creatures. But the one dissenting voice spread disharmony and eventually evil creatures too. The Hobbit was definitely fun and quirky. I loved getting a bit more of the backstory to Fellowship of the Ring via Bilbo, Thorin, and Gandalf, but I much prefer the epic, serious tone of LOTR.

12 & 13. The Madness of Crowds & The War on the West By Douglass Murray. I don't listen to nonfiction audiobooks often, but when I do it's usually because I want to hear the author's own voice, tone, and passion. Murray is the perfect guide. His dark journeys into a dying Europe (and the west more broadly) helped me to better navigate 'the culture wars' as they've been billed in recent years—the dialogues, debates, and violence perpetrated on lines of gender, race, sexuality, ethnicity, class, and national identity. I found his commentary and examples startling, frustrating, and tragic—but important to hear. The tribalism, largely pushed and supported by the left, is profoundly destructive. Most of all though, I think it's important to dwell on Murray's proud and poignant defense of Western civilization's contributions to the world near the end of The War on the West. If you're looking for more Douglass Murray, I appreciated his Uncanceled History series on Youtube.

14. The Eudemian Ethics by Aristotle. Named for the Greek word for happiness, Aristotle's second book on ethics (see his first here) focuses on asking and answering two questions: "What is a good life?" and "How can it be acquired?" I appreciated Aristotle's answer: happiness, which is a result of engaging in activities of virtue, wisdom, and pleasure. He also rebuttals the common answers given: the absence of pain and sickness, happy childhood events, and treating others as means to your ends. Like in his Nicomachean Ethics, I really appreciated Aristotle's thoughts on friendships and how they're crucial to practicing a virtuous life.

15. Cod by Mark Kurlansky. Since at least as far back as the Vikings circa 985 CE, humans have fished cod. In fact, over twelve billion pounds are caught and consumed yearly. The largest and meatiest are off the coast of Massachusetts. However, cod is more of a delicacy now due to overfishing. In an attempt to regenerate the populations, Finland, Norway, Iceland, and other countries have put moratoriums on fishing cod for 5+ year periods. Kurlansky shows the enormous economic and cultural impact that one fish in the ocean has played for a thousand years. You may also love Paper and Salt by the author. His ability to shine a light on seemingly commonplace objects and make connections to the rest of the world is really impressive. I plan to read both Milk and Salmon in 2024. [JG]

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

| THE BEST BOOKS OF 2022 An American slave, a blind anti-fascist, Aristotle, Yellowstone wolves, and more... THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 Climbing Kilimanjaro, practicing Roman virtues, a smart octopus, and more... | THE BEST BOOKS OF 2021 The Dwarf King, personality archetypes, creepy suburbs, Nietzsche, Taleb, and more... THE BEST BOOKS OF 2019 An Alaskan odyssey, NY restauranteurs, seven Gothic tales, the war of art, & more... |