Dear Friends and Readers:

2021 was a year of tremendous, surprising growth for me professionally and personally. I was struck at the variety of new, unplanned experiences. I'm grateful for each of them in their own way, because I learned more about myself, friends, and family members in deeper ways.

Some moments that come to mind include my departure from an ed-tech startup I helped grow for nearly four years and decision to pursue e-commerce growth work, observing cultural differences and dating expectations play out in a relationship, and completing a full year of therapy with a licensed councilor.

In 2021, I also completed an online Executive MBA, thankfully recovered from the Covid-19 Delta variant (Zinc and Vitamin D supplements help), was able to attend the last lecture of one of my philosophical heroes, celebrated with my sister and new brother-in-law at their wedding, visited my family for Christmas and New Years, wrote more fiction in 2021 than in the previous three years combined, and, of course, treasured so many (new) books along the way.

Below are my ten favorite reads in 2021. Some fiction. Some nonfiction. All left their mark on me. I hope some speak to you too. A special thank-you to actor Steven Schub for lunch and his recommendation to explore #10, Panagiota Hatzis for encouraging me to take yet another personality test and delve into #9, as well as Adam Edmonsond for a series of discussions on #2 that at this point have spanned multiple years and eggs Benedict brunches.

Wishing you all a healthy, wealthy, and wise 2022.

Jon

P.S. Here are my Top 10 roundups from 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, and 2015.

P.P.S. You can subscribe to the Reading List for even more. Each month, I'll email you 3-6 books that I absolutely couldn't put down—usually a mix of fiction and nonfiction. I try to steer clear of bestseller (fake) lists, and instead explore authors who challenge my worldview, enchant me through language, and model how to act more effectively and nobly.

2021 was a year of tremendous, surprising growth for me professionally and personally. I was struck at the variety of new, unplanned experiences. I'm grateful for each of them in their own way, because I learned more about myself, friends, and family members in deeper ways.

Some moments that come to mind include my departure from an ed-tech startup I helped grow for nearly four years and decision to pursue e-commerce growth work, observing cultural differences and dating expectations play out in a relationship, and completing a full year of therapy with a licensed councilor.

In 2021, I also completed an online Executive MBA, thankfully recovered from the Covid-19 Delta variant (Zinc and Vitamin D supplements help), was able to attend the last lecture of one of my philosophical heroes, celebrated with my sister and new brother-in-law at their wedding, visited my family for Christmas and New Years, wrote more fiction in 2021 than in the previous three years combined, and, of course, treasured so many (new) books along the way.

Below are my ten favorite reads in 2021. Some fiction. Some nonfiction. All left their mark on me. I hope some speak to you too. A special thank-you to actor Steven Schub for lunch and his recommendation to explore #10, Panagiota Hatzis for encouraging me to take yet another personality test and delve into #9, as well as Adam Edmonsond for a series of discussions on #2 that at this point have spanned multiple years and eggs Benedict brunches.

Wishing you all a healthy, wealthy, and wise 2022.

Jon

P.S. Here are my Top 10 roundups from 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, and 2015.

P.P.S. You can subscribe to the Reading List for even more. Each month, I'll email you 3-6 books that I absolutely couldn't put down—usually a mix of fiction and nonfiction. I try to steer clear of bestseller (fake) lists, and instead explore authors who challenge my worldview, enchant me through language, and model how to act more effectively and nobly.

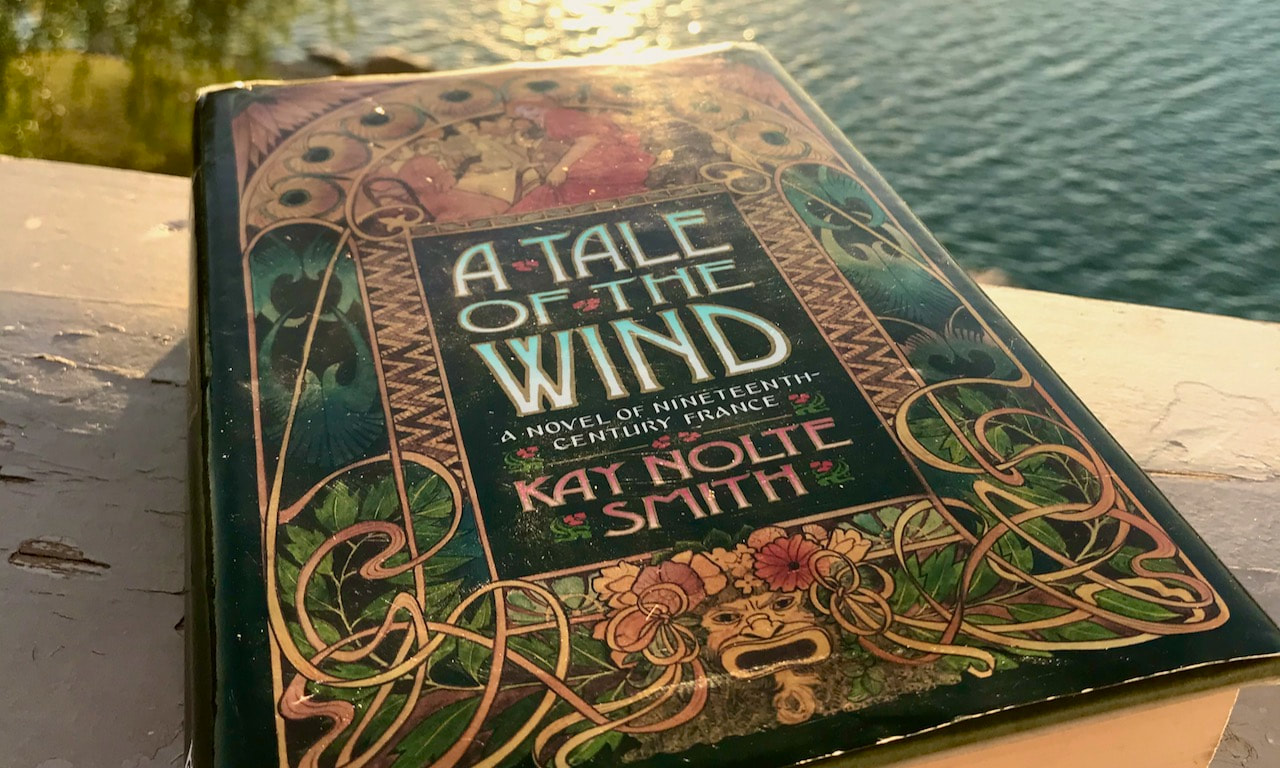

10. A TALE OF THE WIND

Kay Nolte Smith

Kay Nolte Smith

Hardcover | 516 Pages

"When he looked back and tried to understand how it happened, for surely a man would be able to explain the things that altered the course of his life, he could say only that he had felt pierced by the sight of her, on the street corner, in the dawn."

I have a friend and actor in Hollywood who recommended this novel to me years ago. We share a love for Ayn Rand's novels, and Kay Nolte Smith the author of this one, I learned, was for a time at least a close friend of hers. A Tale of the Wind follows a dwarf actor struggling to make his mark on the Parisian theatre, overcoming prejudice, poverty, and political unrest. Apparently, Peter Dinklage, who played Tyrion Lannister on HBO's The Game of Thrones, loves this novel too and is trying to turn it into a mini-series. Fingers crossed!

What I appreciated about A Tale of the Wind was the world-building of 1820-1860 Paris. It felt alive with color and culture: the working-class neighborhoods, the aspiring-artist undergrounds, the cultural and political revolution in response to the upper class privilege. I think it was achieved in large part to the author's zooming-in on small details. Nolte Smith's brevity of language is crisp and clear, bridging the complex emotional tones of the characters and scenes with just a few words: "a stiff nod", "The kindness was cold water that shocked Jeanne's mind back to life...", "The cat mewed, protesting the increased pressure on his head.", "The shopkeeper's brow rose in a moon of amusement."

If you're looking for a magnanimous central character, strong and interesting female characters, and a ticket back to a both sunlit and shadowy Paris with winds of change stirring, try A Tale of the Wind.

What I appreciated about A Tale of the Wind was the world-building of 1820-1860 Paris. It felt alive with color and culture: the working-class neighborhoods, the aspiring-artist undergrounds, the cultural and political revolution in response to the upper class privilege. I think it was achieved in large part to the author's zooming-in on small details. Nolte Smith's brevity of language is crisp and clear, bridging the complex emotional tones of the characters and scenes with just a few words: "a stiff nod", "The kindness was cold water that shocked Jeanne's mind back to life...", "The cat mewed, protesting the increased pressure on his head.", "The shopkeeper's brow rose in a moon of amusement."

If you're looking for a magnanimous central character, strong and interesting female characters, and a ticket back to a both sunlit and shadowy Paris with winds of change stirring, try A Tale of the Wind.

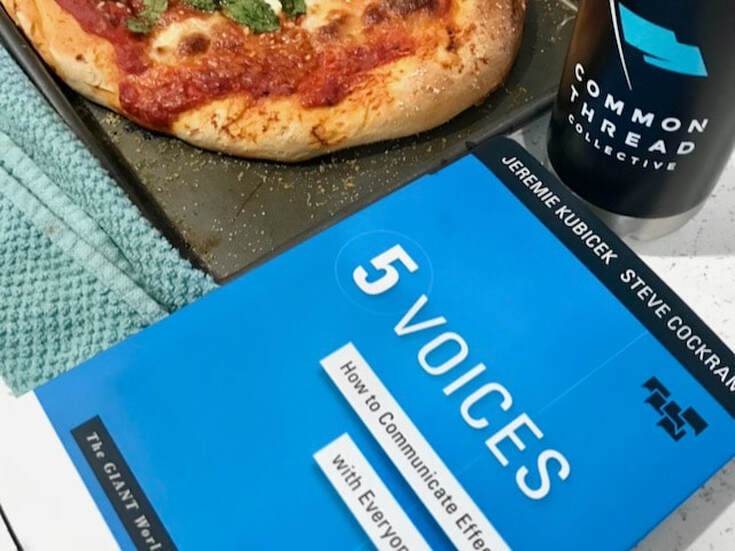

9. THE FIVE VOICES

Jereme Kubicek & Steve Cockram

Jereme Kubicek & Steve Cockram

"We all have a leadership voice, which is what others experience on the other side of us. It's made up of a complex mix of the five separate voices."

You've likely heard of The Five Love Languages (Words of Affirmation, Touch, Acts of Service, Gifts, Quality Time), but have you ever heard of The Five Voices? They are Creative, Nurturer, Guardian, Connector, and Pioneer. These archetypes I have found firsthand, are super helpful lenses to see yourself and others through. Test results show that my primary Voice is Guardian and my smallest, or 'nemesis' voice, is Connector.

The core premise, much like Five Love Languages, is that people often want to communicate and be communicated to in different ways, and different voices value different things. For instance, Guardians have a reverence for order and traditions. They steward money entrusted to them with a great sense of responsibility. Nurturers are focused on people's health around them and team dynamics and inter-personal relationships. By knowing your dominant voice and how the other voices fall in priority for you, can give self-awareness and help one communicate more effectively with those who have different voices.

I'm reminded of the ancient Greek's pantheon of gods—Ares, the god of war, Athena the goddess of wisdom, Nike the goddess of victory, Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Their creators deified human emotions to make sense of themselves and others. I think that is a very sophisticated way of mapping one's inner landscape. In this modern era, maybe more now than ever, humans have a pantheon of personalities, emotions, and influencers inside our minds. And I'm grateful for a bit more insight from The Five Voices.

The core premise, much like Five Love Languages, is that people often want to communicate and be communicated to in different ways, and different voices value different things. For instance, Guardians have a reverence for order and traditions. They steward money entrusted to them with a great sense of responsibility. Nurturers are focused on people's health around them and team dynamics and inter-personal relationships. By knowing your dominant voice and how the other voices fall in priority for you, can give self-awareness and help one communicate more effectively with those who have different voices.

I'm reminded of the ancient Greek's pantheon of gods—Ares, the god of war, Athena the goddess of wisdom, Nike the goddess of victory, Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Their creators deified human emotions to make sense of themselves and others. I think that is a very sophisticated way of mapping one's inner landscape. In this modern era, maybe more now than ever, humans have a pantheon of personalities, emotions, and influencers inside our minds. And I'm grateful for a bit more insight from The Five Voices.

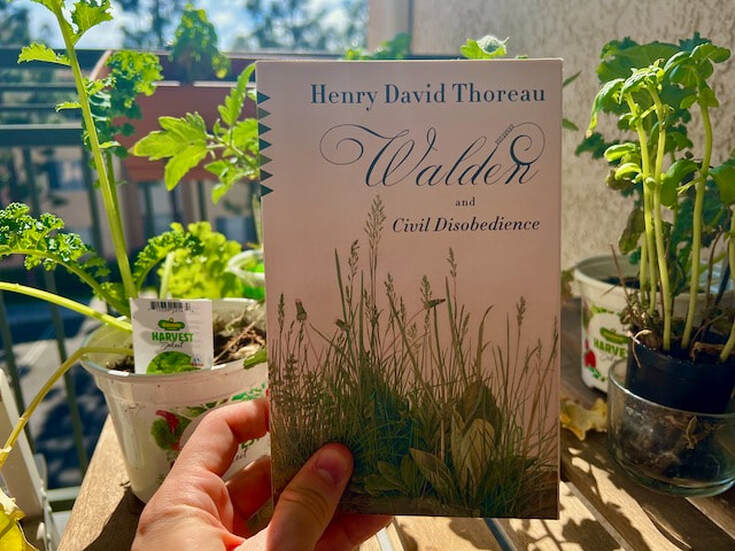

8. WALDEN

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau

"The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation," Thoreau wrote in 1845 at Walden Pond near Concord, Massachusetts. And some pages later, "I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn that it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived." I first came upon these words in high school via a movie day of Dead Poet's Society. The existentialist teacher Mr. Keating, played by Robin Williams, has

his students read Thoreau's work. These quotes have haunted me since. A beautiful cover by Vintage Classics in a local indie bookshop was enough to finally tip me over the edge (14 years post high school) and read Walden and Civil Disobedience.

Thoreau was twenty-eight years old when he went into a two-years-long exile. He built a cabin and labored with his own hands to feed and cloth himself. I really appreciated this part-memoir, part-treatise on living well. He has quiet, yet strong opinions on life and luxury; he feared in 1845 that too many men had "forged their own golden or silver fetters" and were not truly free nor were they happy. "Renew yourself completely each day; do it, again and again, and forever again," he writes. Throughout Walden he summons parables from the far east and western antiquity, as well as blending his own thoughts on the health of solitude and trips into nature, the value of house-warming rituals, prudent spending, the importance of reading ;) — "How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book?" — and the dangers of modern jobs — "Man has become the tools of their tools."

If you're looking for some brother books to Walden, try One Man's Wilderness by Dick Proenneke, The Life and Autobiography of Frederick Douglass, and the stoic Epictetus's Discourses, all of which I've read and recommended before. If you want videos on self-reliance and off-grid living, check out My Self Reliance on YouTube. This guy builds cabins, saunas, and outdoor kitchens mostly by hand; he hunts, foragers and gardens, and plays fetch with his golden retriever in northern Ontario.

his students read Thoreau's work. These quotes have haunted me since. A beautiful cover by Vintage Classics in a local indie bookshop was enough to finally tip me over the edge (14 years post high school) and read Walden and Civil Disobedience.

Thoreau was twenty-eight years old when he went into a two-years-long exile. He built a cabin and labored with his own hands to feed and cloth himself. I really appreciated this part-memoir, part-treatise on living well. He has quiet, yet strong opinions on life and luxury; he feared in 1845 that too many men had "forged their own golden or silver fetters" and were not truly free nor were they happy. "Renew yourself completely each day; do it, again and again, and forever again," he writes. Throughout Walden he summons parables from the far east and western antiquity, as well as blending his own thoughts on the health of solitude and trips into nature, the value of house-warming rituals, prudent spending, the importance of reading ;) — "How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book?" — and the dangers of modern jobs — "Man has become the tools of their tools."

If you're looking for some brother books to Walden, try One Man's Wilderness by Dick Proenneke, The Life and Autobiography of Frederick Douglass, and the stoic Epictetus's Discourses, all of which I've read and recommended before. If you want videos on self-reliance and off-grid living, check out My Self Reliance on YouTube. This guy builds cabins, saunas, and outdoor kitchens mostly by hand; he hunts, foragers and gardens, and plays fetch with his golden retriever in northern Ontario.

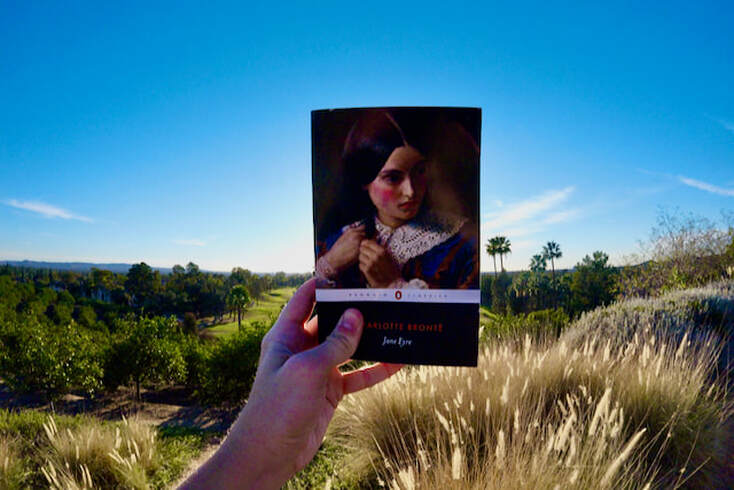

7. JANE EYRE

Charlotte Bronte

Charlotte Bronte

"The more solitary, the more friendless, the more unsustained I am, the more I will respect myself." — Charlotte Bronte, Jane Eyre

In 2021, I reread Jane Eyre and still appreciate it so much. The movies tend to focus on the romance with Mr. Rochester, but the story is broader and aims to paint a portrait of a type of person. Jane is fiercely independent and struggles to establish her personal freedom throughout. I especially love the first one hundred or so pages with young Jane and still relate to some of the overbearing, oppressive-even adults and peers against whom she struggled to establish her own ideas and values. Plus who doesn't love a fiery, cathartic ending and uncovering the haunted pasts of characters?

6. BEYOND ORDER: TWELVE MORE RULES FOR LIFE

Dr. Jordan B. Peterson

Dr. Jordan B. Peterson

"Order is explored territory. We are in order when the actions we deem appropriate produce the results we aim at...Chaos is anomaly, novelty, unpredictability, transformation, disruption, and all too often descent...Sometimes it reveals itself gently...other times the unexpected makes itself known terribly." — Jordan B. Peterson, Beyond Order

Dr. Jordan B. Peterson is a psychologist who has "taught mythology to doctors...consulted for the UN Secretary General...helped his clinical clients manage depression...served as an advisor to senior partners of major law firms..." and published more than one hundred scientific papers on personality development. His first book, Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief, explores the psychology of religion and the universal values contained in our collective, ancient myths.

He's exploded into an online sensation as a part of The Intellectual Dark Web, as a sort of pre-eminent father figure, Dr. Jordan B. Peterson, has written a second unconventionally inspiring and instructive manual for dealing with career, romance, family, and personal meaning. I've found a tremendous amount of practical insights from his analysis of biblical and archetypal stories, his mining of history to courageously look at mankind in its worst moments, and his synthesizing of biological and psychological research to understand how societies fail and function. Because of Peterson, I'm not as lazy, messy, bitter, resentful, angry, and pitiful. I see the implications for such chaos a bit more clearly. I hope others begin to help themselves too.

If you're interested in videos instead, try these:

YOUTUBE

GUEST APPEARANCES

He's exploded into an online sensation as a part of The Intellectual Dark Web, as a sort of pre-eminent father figure, Dr. Jordan B. Peterson, has written a second unconventionally inspiring and instructive manual for dealing with career, romance, family, and personal meaning. I've found a tremendous amount of practical insights from his analysis of biblical and archetypal stories, his mining of history to courageously look at mankind in its worst moments, and his synthesizing of biological and psychological research to understand how societies fail and function. Because of Peterson, I'm not as lazy, messy, bitter, resentful, angry, and pitiful. I see the implications for such chaos a bit more clearly. I hope others begin to help themselves too.

If you're interested in videos instead, try these:

YOUTUBE

- The Biblical Lecture Series — 12 lectures (2 hrs per) on key stories found in Genesis and Exodus.

- The Death and Resurrection of Christ — a compilation of talks on the metaphorical truths of the story of Christ

- Maps of Meaning — 12 lectures (2 hrs per) on key aspects of religious and mythic narratives, from Pinocchio and St. Bernard to Babel and Buddha

GUEST APPEARANCES

- Jocko Podcast, Episode 98

- Jocko Podcast, Episode 112

- Jocko Podcast, Episode 155

- Joe Rogan Podcast, Episode 877

- Joe Rogan Podcast, Episode 1070

- Joe Rogan Podcast, Episode 1208

- Joe Rogan Podcast, Episode 1139

5. SELECTED WRITINGS

Cicero

Cicero

“Six mistakes mankind keeps making century after century:

Believing that personal gain is made by crushing others;

Worrying about things that cannot be changed or corrected;

Insisting that a thing is impossible because we cannot accomplish it;

Refusing to set aside trivial preferences;

Neglecting development and refinement of the mind;

Attempting to compel others to believe and live as we do.”

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, circa 40 B.C.

Believing that personal gain is made by crushing others;

Worrying about things that cannot be changed or corrected;

Insisting that a thing is impossible because we cannot accomplish it;

Refusing to set aside trivial preferences;

Neglecting development and refinement of the mind;

Attempting to compel others to believe and live as we do.”

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, circa 40 B.C.

Marcus Tulius Cicero (106-43 B.C.) was a lawyer, philosopher, statesman, and staunch defender of the Roman republic. In his time, he was celebrated as a master orator and has influenced many generations since with his two most famous philosophical treatises, On Duties and On Old Age.

On Duties

With respect to the first On Duties he is addressing much of it to his own son, something I find so refreshing and grounding—the application of philosophical ideas to everyday living. In it, he is trying to find a rule or code of ethics that integrates the stoic idea of "living consistently with nature," and, Cicero believes, continue Socrates' own tradition of cursing men who sought to parse the good from 'the advantageous' (or practical).

He concludes that "Every man must bear his own misfortunes rather than remedy them by damaging someone else," to not destroy the "fellowship" of mankind and "nature's creation," which is "the link that unites every human being with every other."

On Old Age

Written in Cicero's declining years, he explores the often-overlooked silver linings to aging: giving attention to children and the future generations more than self, learning to be in nature and farm without as much sexual lusting and distractions—"He plants trees for the use of another age." I really appreciated the perennial relevance to this treatise and the spirit of optimism in the face of declining health. This is a noble act of knowing and celebrating what a person can control and what one cannot.

On Duties

With respect to the first On Duties he is addressing much of it to his own son, something I find so refreshing and grounding—the application of philosophical ideas to everyday living. In it, he is trying to find a rule or code of ethics that integrates the stoic idea of "living consistently with nature," and, Cicero believes, continue Socrates' own tradition of cursing men who sought to parse the good from 'the advantageous' (or practical).

He concludes that "Every man must bear his own misfortunes rather than remedy them by damaging someone else," to not destroy the "fellowship" of mankind and "nature's creation," which is "the link that unites every human being with every other."

On Old Age

Written in Cicero's declining years, he explores the often-overlooked silver linings to aging: giving attention to children and the future generations more than self, learning to be in nature and farm without as much sexual lusting and distractions—"He plants trees for the use of another age." I really appreciated the perennial relevance to this treatise and the spirit of optimism in the face of declining health. This is a noble act of knowing and celebrating what a person can control and what one cannot.

4. BEYOND GOOD AND EVIL

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche

"With the strength of his spiritual sight and insight the distance, and as it were the space, around man continually expands: his world grows deeper, ever new stars, ever new images and enigmas come into view." — Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

I really enjoyed my first read of Nietzsche, a German philosopher who holds no punches back. Beyond Good and Evil is formatted as a series of numbered essays, paragraphs, and even tweet-sized maxims, from 1-300. This format helped me to better recall his views since he is traveling around topics a lot: music and art, European culture, Christianity, ancient philosophers including the stoics, loneliness, a Superman's will to power, and much more.

I took nearly 30 pages of notes and quotes, quite a bit for me, and at the end summary, wrote simply "powerful and fascinating." Nietzsche's Superman is one questing with unquenchable, noble "will to power" to defeat his base, common attributes—and those, it seems, of others. This "will to power" is core to what he calls a "master morality," and largely unknown by the common man, who collectively follow a "slave morality." At its core, the slave morality has a concept of a God, and also 'baptized truths' such as Kant's categorical imperative and the works of Spinoza that actually perpetuate self-tyranny.

With respect to the title of the work, Nietzsche is laying out an indictment of the then-current morality of 1800's Europe as well as a declaration of freedom for the Superman, who alone can transcend 'Good and Evil' (as the world sees those concepts) in order to manifest his true potential. Since reading it, I've started worshipping myself. Kidding. But I did pick up Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and plan to read many of his other works. If you have recommendations, please let me know. I'd appreciate it so much. This guy is intriguing, but complex.

I took nearly 30 pages of notes and quotes, quite a bit for me, and at the end summary, wrote simply "powerful and fascinating." Nietzsche's Superman is one questing with unquenchable, noble "will to power" to defeat his base, common attributes—and those, it seems, of others. This "will to power" is core to what he calls a "master morality," and largely unknown by the common man, who collectively follow a "slave morality." At its core, the slave morality has a concept of a God, and also 'baptized truths' such as Kant's categorical imperative and the works of Spinoza that actually perpetuate self-tyranny.

With respect to the title of the work, Nietzsche is laying out an indictment of the then-current morality of 1800's Europe as well as a declaration of freedom for the Superman, who alone can transcend 'Good and Evil' (as the world sees those concepts) in order to manifest his true potential. Since reading it, I've started worshipping myself. Kidding. But I did pick up Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and plan to read many of his other works. If you have recommendations, please let me know. I'd appreciate it so much. This guy is intriguing, but complex.

3. ATLAS SHRUGGED & THE FOUNTAINHEAD

Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand

"Dagny, I'll always bow to a coat-of-arms. I'll always worship the symbols of nobility... Only…the coat-of-arms of our day are to be found on billboards and in the ads of popular magazines.”

— Francisco d'Anconia, Atlas Shrugged

— Francisco d'Anconia, Atlas Shrugged

"But you see...I have, let’s say, sixty years to live. Most of that time will be spent working. I’ve chosen the work I want to do. If I find no joy in it, then I’m only condemning myself to sixty years of torture. And I can find the joy only if I do my work in the best way possible to me. But the best is a matter of standards—and I set my own standards. I inherit nothing. I stand at the end of no tradition. I may, perhaps, stand at the beginning of one.” ― Howard Roark, The Fountainhead

Atlas Shrugged

57 hours. That's how long the Audible version of Ayn Rand's magnum opus is from the iconic, thematic opening line "Who is John Galt?" to the 600,000+ word answer's final scene. The journey was familiar and nostalgic, but also fascinating and new for me. I had read Atlas Shrugged twice cover to cover before, once eleven years ago and then again three years later and so I felt overdue for a revisit to a novel and its creator who has meant so much to me over the years and shaped my world view.

In particular, I appreciated the character of Henry Rearden more, and his internal struggle to integrate the virtues of his productive activities with those of his romantic needs. I found myself noticing Rand's use of financial concepts (currency, bankruptcy, gold, account overdrawn, etc.) with moral evaluations and value judgements, something I had only vaguely noticed before. I fell in love again with the end of Part II, in which Dagny pilots a plane to pursue a mysterious man's own aircraft over the Rocky Mountains. And much more.

Rand's heroes—both their actions and their speeches throughout—continue to inspire me and stir up many conversations in my own mind or with myself and others about philosophy, ethics, art, politics, and American culture.

57 hours. That's how long the Audible version of Ayn Rand's magnum opus is from the iconic, thematic opening line "Who is John Galt?" to the 600,000+ word answer's final scene. The journey was familiar and nostalgic, but also fascinating and new for me. I had read Atlas Shrugged twice cover to cover before, once eleven years ago and then again three years later and so I felt overdue for a revisit to a novel and its creator who has meant so much to me over the years and shaped my world view.

In particular, I appreciated the character of Henry Rearden more, and his internal struggle to integrate the virtues of his productive activities with those of his romantic needs. I found myself noticing Rand's use of financial concepts (currency, bankruptcy, gold, account overdrawn, etc.) with moral evaluations and value judgements, something I had only vaguely noticed before. I fell in love again with the end of Part II, in which Dagny pilots a plane to pursue a mysterious man's own aircraft over the Rocky Mountains. And much more.

Rand's heroes—both their actions and their speeches throughout—continue to inspire me and stir up many conversations in my own mind or with myself and others about philosophy, ethics, art, politics, and American culture.

The Fountainhead

When I first read The Fountainhead in college I remember feeling relieved, but not because I saw a vision of the ideal, as its author wanted. At the time, I didn't understand Howard Roark's seemingly suicidal commitment to his principles. In fact, my relief came when I read the opening scene of Chapter 1, Part IV, in which a young boy “riding his bicycle down a forgotten trail...wanted to decide whether life was worth living.” Like him I “didn’t know that this was the question in [my] mind” — and had been for as far back as I could remember.

Growing up, I felt at times that much of life was some form of damnation to a "quarry," one unchosen and unwanted, but a necessary consequence of dreaming. I associated more with Dominique Francon and Gail Wynand than the protagonist. But Roark’s integrity to his principles and conscious understanding of why his dreams were actually his deliverance was the feast of courage I’d been starving to see. I’m still eating eleven years later.

In 2021, I listened to it on Audible and really enjoyed the experience. Roark's intransigent journey to design and build by his own standards, and overcoming obstacles and temptations to conform, was renewed by the emotionally performed dialogue and exposition.

When I first read The Fountainhead in college I remember feeling relieved, but not because I saw a vision of the ideal, as its author wanted. At the time, I didn't understand Howard Roark's seemingly suicidal commitment to his principles. In fact, my relief came when I read the opening scene of Chapter 1, Part IV, in which a young boy “riding his bicycle down a forgotten trail...wanted to decide whether life was worth living.” Like him I “didn’t know that this was the question in [my] mind” — and had been for as far back as I could remember.

Growing up, I felt at times that much of life was some form of damnation to a "quarry," one unchosen and unwanted, but a necessary consequence of dreaming. I associated more with Dominique Francon and Gail Wynand than the protagonist. But Roark’s integrity to his principles and conscious understanding of why his dreams were actually his deliverance was the feast of courage I’d been starving to see. I’m still eating eleven years later.

In 2021, I listened to it on Audible and really enjoyed the experience. Roark's intransigent journey to design and build by his own standards, and overcoming obstacles and temptations to conform, was renewed by the emotionally performed dialogue and exposition.

| 2. THE BED OF PROCRUSTES, THE BLACK SWAN, & SKIN IN THE GAME Nassim Nicholas Taleb |

“The three most harmful addictions are heroin, carbohydrates, and a monthly salary."

— Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Bed of Procrustes

— Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Bed of Procrustes

"My principal activity is to tease those who take themselves and the quality of their knowledge too seriously," writes Nassim Nicholas Taleb in the Introduction to Fooled By Randomness, his first work in the Incerto series. It includes such bestsellers as The Black Swan and Anti-Fragile, and Skin in the Game. As a financial investor for over two decades, Taleb's books combine philosophy, mathematics, and probability and applies them to practical problems.

Themes in NNT's work include his distrust for experts, a kind of rough, Roman virtue that necessitates calling out pseudo-experts and institutions, his fascination with stoic philosophers, especially Epictetus, and his focus on correcting psychological biases. One such bias is Survivorship Bias, which scientific research and development is filled with. Research that yields no results does not go to print. However, in truth there may be great information in the fact that nothing took place.

A close friend has been recommending Nassim Nicholas Taleb to me for years, and I was so glad to have finally encountered him. His iconoclastic, moral-toned, yet humorous exploration of self-knowledge and it's slippery nature was so refreshing.

The Bed of Procrustes

Procrustes was a villain from Greek myths who abducted travelers into his home and had them lay in a bed. The short ones were painfully stretched to fit the bed; those too long were cut down to size. “…we humans, facing limits of knowledge, and things we do not observe, the unseen and the unknown, resolve the tension by squeezing life and the world into crisp commoditized ideas, reductive categories, specific vocabularies, and prepackaged narratives, which, on the occasion has explosive consequences…” as an example, “few realize that we are changing the brains of school children through medication in order to make them adjust to the curriculum, rather than the reverse.” I appreciate Nassim Taleb’s short book of aphorisms and his aim to undo some Procrustean damage by questioning common but unnatural ideas. Too many to list here, but one I've thought of a lot lately: “The three most harmful addictions are heroin, carbohydrates, and a monthly salary."

The Black Swan

"The Black Swan is about epistemic limitations, then, from this definition, we can see that it is not about some objectively defined phenomenon, like rain or a car crash—it is simply something that was not expected by a particular observer." What I take from this book is the importance, but difficulty of knowing what you do not know, and the virtue of taking steps to reduce your vulnerabilities to fatal risks.

Skin In the Game

Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s Silver Rule: “do not treat others the way you would not like to be treated.” Expressed “Via Negativa” because we know what is wrong with more clarity than what is right, and that knowledge grows by subtraction too. Relatedly, it's easier to know something is wrong than to find the solution. This book has four big topics: 1. uncertainty and the reliability of knowledge 2. symmetry in human affairs 3. information sharing in transactions and 4. rationality in complex systems and the real world.

Themes in NNT's work include his distrust for experts, a kind of rough, Roman virtue that necessitates calling out pseudo-experts and institutions, his fascination with stoic philosophers, especially Epictetus, and his focus on correcting psychological biases. One such bias is Survivorship Bias, which scientific research and development is filled with. Research that yields no results does not go to print. However, in truth there may be great information in the fact that nothing took place.

A close friend has been recommending Nassim Nicholas Taleb to me for years, and I was so glad to have finally encountered him. His iconoclastic, moral-toned, yet humorous exploration of self-knowledge and it's slippery nature was so refreshing.

The Bed of Procrustes

Procrustes was a villain from Greek myths who abducted travelers into his home and had them lay in a bed. The short ones were painfully stretched to fit the bed; those too long were cut down to size. “…we humans, facing limits of knowledge, and things we do not observe, the unseen and the unknown, resolve the tension by squeezing life and the world into crisp commoditized ideas, reductive categories, specific vocabularies, and prepackaged narratives, which, on the occasion has explosive consequences…” as an example, “few realize that we are changing the brains of school children through medication in order to make them adjust to the curriculum, rather than the reverse.” I appreciate Nassim Taleb’s short book of aphorisms and his aim to undo some Procrustean damage by questioning common but unnatural ideas. Too many to list here, but one I've thought of a lot lately: “The three most harmful addictions are heroin, carbohydrates, and a monthly salary."

The Black Swan

"The Black Swan is about epistemic limitations, then, from this definition, we can see that it is not about some objectively defined phenomenon, like rain or a car crash—it is simply something that was not expected by a particular observer." What I take from this book is the importance, but difficulty of knowing what you do not know, and the virtue of taking steps to reduce your vulnerabilities to fatal risks.

Skin In the Game

Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s Silver Rule: “do not treat others the way you would not like to be treated.” Expressed “Via Negativa” because we know what is wrong with more clarity than what is right, and that knowledge grows by subtraction too. Relatedly, it's easier to know something is wrong than to find the solution. This book has four big topics: 1. uncertainty and the reliability of knowledge 2. symmetry in human affairs 3. information sharing in transactions and 4. rationality in complex systems and the real world.

1. THE STEPFORD WIVES

Ira Levin

Ira Levin

"That's what she was, Joanna felt suddenly. That's what they all were, all the Stepford Wives: actresses in commercials, pleased with detergent and floor wax, with cleaners, shampoos, and deodorants. Pretty actresses, big in the bosom but small in the talent, playing suburban housewives unconvincingly, too nicey-nice to be real." — Ira Levin, The Stepford Wives

Ira Levin is a rare bird, an author whose novels and plays satirize, thrill, and introspect with a brevity that is almost unparalleled. I am in awe of his short, crisp, direct declarative statements that advance the four-month-long story of Joanna moving with her family into Stepford. His transitions are seamless, hidden in plain sight: "She was about a third of the way down the stairs going by foot-feel." His descriptions are not just visual but sensual: "A typewriter peck-peck-pecked from the back." And the creepy suburban life is so on point you feel it all right alongside Joanna with each weird, escalating encounter.

If you're looking for a single-afternoon-sized atmospheric thriller, The Stepford Wives is the perfect one to pick up. And if you're looking for a play and movie of the same, try Levin's Deathtrap. It is the longest running Broadway play in history. The film version is excellent too and stars Michael Caine and Christopher Reeves.

If you're looking for a single-afternoon-sized atmospheric thriller, The Stepford Wives is the perfect one to pick up. And if you're looking for a play and movie of the same, try Levin's Deathtrap. It is the longest running Broadway play in history. The film version is excellent too and stars Michael Caine and Christopher Reeves.

CAN'T FORGET ABOUT THESE TOO ...

Picking just ten books is a tough task. There were just so many spectacular stories that I stumbled upon, devoured, reread, and emphatically recommended in 2021. Which is why I wanted to share another dozen or so below. Whether you pick up one or all of them, from above or below, now or in the future, I hope that they give you as much inspiration and instruction as they have given me!

1. The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mandel, the Father of Genetics by Robin Marantz Henig. Remember high school biology class about the guy who grew different pea pods and discovered recessive and dominant traits? This is his story. The parallels between his pea pod breeding and A/B testing Facebook ads are fascinating (I work in digital marketing).

2. Watership Down by Richard Adams. I love anthropomorphic fiction. The friendship of the rabbits Bigwig and Hazel, the terrifying danger of a black cat in the night or a group of men with a bulldozer, the animals' gathering and telling of old stories to face the storm outside, the longing for a distant dream and the discipline to reach it, the mysteries of death and the afterlife—all these stitch together to form an odyssey of rabbits that is so human.

3. Dune by Frank Herbert. Cracked this open after watching the new Dune movie series with Timothée Chalamet and Zendaya. I appreciated the second-half of the book too and can't wait to see a visual translation of the story's conclusion.

4. The Rise of America: Remaking the World Order by Marin Katusa. There's a seemingly endless wave of anxiety and cynicism about America's future. It seems to have been going on for twenty years, since 9/11. But I really enjoyed this alternate, reasoned perspective on why America may not just weather the economic, crypto, environmental, and foreign policy issues but excel. Marin Katusa is a Canadian author and independent investor. He makes some very interesting predictions about the US in the next 10-20 years.

5. The Bird Way: A New Look at How Birds Talk, Work, Play, Parent, and Think by Jennifer Ackerman. There are 400 billion birds on earth. That's 80 per human. And yet, for as resourceful and resilient as the feathered species are, author and "bird nerd" Jennifer Ackerman contends we still know very little about—and worse, largely dismiss—them. Birds make tools. They count. They imitate behaviors of other birds and humans. They invent new solutions to old problems. They remember where they put things. They can anticipate and guard against storms. They exploit opportunities. They teach their hatchlings, and much more.

6. The Fourth Turning by William Strauss and Neil Howe. The premise of this book is that history moves in four cycles, typically 20-25 years (one generation). First comes a High, a period of "confident expansion" as a new order takes root after the old world is swept away. Second: an Awakening, "a time of spiritual exploration and rebellion" against the new order. Third: Unraveling, "an increasingly troubled era in which individualism triumphs over crumbling institutions". Last: Crisis, a.k.a the Fourth Turning, "when society passes through a great and perilous gate in history." I found the examples very compelling, and also was haunted by an idea I uncovered years earlier held by Thomas Jefferson, in which he wondered whether the U.S. Constitution should have a generational expiration date. This would require civic involvement and a new Constitution to be written, ratified, and upheld with real skin in the game by young and old citizens alike.

7. The Light Ages: The Surprising Story of Medieval Sciences by Seb Falk. An interesting history of some breakthroughs in medieval science: alchemy and early chemistry, physics and astronomy, clocks/time, mathematics, architecture, and more...

8. The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis. Young adult fantasy and children's stories are still some of my favorite. A friend recommended I give LWW a shot and I'm so glad I did. The Christian parable was funny, scary, fantastical, redeeming and a fast flight through the illustrated story.

9. Dare to Lead by Brene Brown. I discovered Brene Brown's Daring Greatly years ago via Chase Jarvis Live and continue to appreciate her perspective on communication in the workplace, resolution in relationships, and improvoing on self-awareness through introspection.

10. The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco. A murder mystery set in 14th-century England. Deeper, it's a philosophical battle between reason and faith. Brother William of Baskerville's logical process leads him to discover the truths of the murders, while the Catholic priests' faith leads them to blind obedience. Nassim Taleb is also a big fan of Eco's anti-library concept, which I find interesting.

11. The 50th Law by 50 Cent and Robert Greene. I loved this part-bio, part-instruction manual on how to overcome fear in life and business. “Having a brush with death, or being reminded in a dramatic way of the shortness of our lives, can have a positive, therapeutic effect. Our days are numbered and so it is best to make every moment count, to have a sense of urgency about life."

12. The Spy Who Loved Me and On Her Majesty's Secret Service by Ian Fleming. Spy is the only first-person James Bond adventure, and it's told from the perspective of his lover, Vivienne Michel. I loved the 3-part structure: Me, Them, Him. 10 pages per chapter in Part 1. By 60 pages in, we know why Vivienne's come to Dreamy Pines, NY and whom she's run away from—two men who used her. The cathartic journey with Bond against a pair of mafioso is fast and fierce. Bond helps her overcome her fears to fight and not flee anymore.

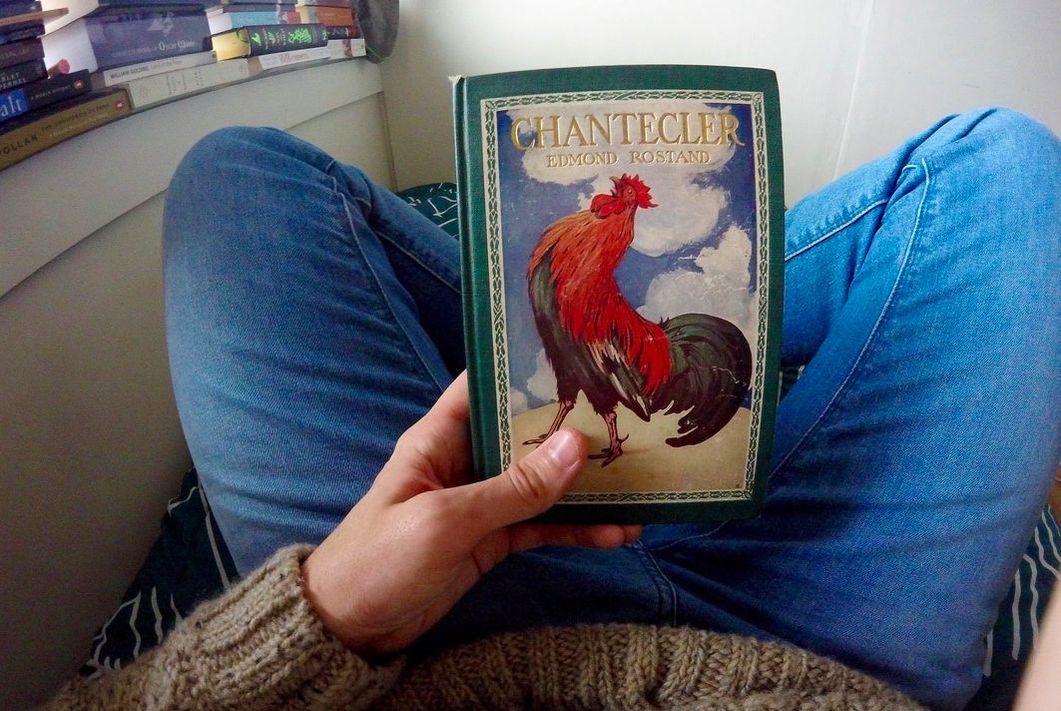

13. The Woman of Samaria and Don Juan, two plays by Edmond Rostand. One motif in Rostand's plays is a deep reverence for people who act honorably, yet are often overlooked. The Woman of Samaria reimagines the biblical tale of a dishonored woman who must convince the unfriendly townsfolk to follow her to Jacob's well and see Christ with their own eyes. Second, Don Juan, which reimagines the archetypal seducer's descent toward Hell on a long staircase. A White Shade shows our anti-hero the wreckage he has caused so many women with his sexual conquests. This Shade is in fact the spirit of such heartbroken woman. She acts out of love and forgiveness in order to try and redeem him before he reaches the end of the staircase and enters Hell for eternity.

14. Mythos by Stephen Fry. During California's lockdowns, I returned to acrylic painting, something I enjoyed a lot growing up. In 2021, I spent many a Sunday afternoon or a few hours after work painting and listening to the audible version of Stephen Fry's Mythos. I have loved re-reading Edith Hamilton's Mythology since high school, but hearing Stephen Fry's rendition of the Greek gods, heroes, and antagonists was a dream.

15. The Little Bitcoin Book: Why Bitcoin Matters for Your Freedom, Finances, and Future. This 100-page, multi-authored booklet is a kind of primer on Bitcoin, highlighting various benefits: financial, cultural, personal, and political.

16. The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power, from the Freemasons to Facebook by Niall Ferguson. A dense book navigating time and space: from the modern social media platforms on all of our phones to fighting in Vietnamese jungles, creating the Italian renaissance with polymath interests, building a decentralized British empire in a then-broken world, and so much more. At the book's core I think is the showcasing of networks as inherent unstable and often causing a slow or sudden destruction of hierarchies. The scope of this book is impressive, though I would have liked a stronger conclusion of learnings from the historical examples.

1. The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mandel, the Father of Genetics by Robin Marantz Henig. Remember high school biology class about the guy who grew different pea pods and discovered recessive and dominant traits? This is his story. The parallels between his pea pod breeding and A/B testing Facebook ads are fascinating (I work in digital marketing).

2. Watership Down by Richard Adams. I love anthropomorphic fiction. The friendship of the rabbits Bigwig and Hazel, the terrifying danger of a black cat in the night or a group of men with a bulldozer, the animals' gathering and telling of old stories to face the storm outside, the longing for a distant dream and the discipline to reach it, the mysteries of death and the afterlife—all these stitch together to form an odyssey of rabbits that is so human.

3. Dune by Frank Herbert. Cracked this open after watching the new Dune movie series with Timothée Chalamet and Zendaya. I appreciated the second-half of the book too and can't wait to see a visual translation of the story's conclusion.

4. The Rise of America: Remaking the World Order by Marin Katusa. There's a seemingly endless wave of anxiety and cynicism about America's future. It seems to have been going on for twenty years, since 9/11. But I really enjoyed this alternate, reasoned perspective on why America may not just weather the economic, crypto, environmental, and foreign policy issues but excel. Marin Katusa is a Canadian author and independent investor. He makes some very interesting predictions about the US in the next 10-20 years.

5. The Bird Way: A New Look at How Birds Talk, Work, Play, Parent, and Think by Jennifer Ackerman. There are 400 billion birds on earth. That's 80 per human. And yet, for as resourceful and resilient as the feathered species are, author and "bird nerd" Jennifer Ackerman contends we still know very little about—and worse, largely dismiss—them. Birds make tools. They count. They imitate behaviors of other birds and humans. They invent new solutions to old problems. They remember where they put things. They can anticipate and guard against storms. They exploit opportunities. They teach their hatchlings, and much more.

6. The Fourth Turning by William Strauss and Neil Howe. The premise of this book is that history moves in four cycles, typically 20-25 years (one generation). First comes a High, a period of "confident expansion" as a new order takes root after the old world is swept away. Second: an Awakening, "a time of spiritual exploration and rebellion" against the new order. Third: Unraveling, "an increasingly troubled era in which individualism triumphs over crumbling institutions". Last: Crisis, a.k.a the Fourth Turning, "when society passes through a great and perilous gate in history." I found the examples very compelling, and also was haunted by an idea I uncovered years earlier held by Thomas Jefferson, in which he wondered whether the U.S. Constitution should have a generational expiration date. This would require civic involvement and a new Constitution to be written, ratified, and upheld with real skin in the game by young and old citizens alike.

7. The Light Ages: The Surprising Story of Medieval Sciences by Seb Falk. An interesting history of some breakthroughs in medieval science: alchemy and early chemistry, physics and astronomy, clocks/time, mathematics, architecture, and more...

8. The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis. Young adult fantasy and children's stories are still some of my favorite. A friend recommended I give LWW a shot and I'm so glad I did. The Christian parable was funny, scary, fantastical, redeeming and a fast flight through the illustrated story.

9. Dare to Lead by Brene Brown. I discovered Brene Brown's Daring Greatly years ago via Chase Jarvis Live and continue to appreciate her perspective on communication in the workplace, resolution in relationships, and improvoing on self-awareness through introspection.

10. The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco. A murder mystery set in 14th-century England. Deeper, it's a philosophical battle between reason and faith. Brother William of Baskerville's logical process leads him to discover the truths of the murders, while the Catholic priests' faith leads them to blind obedience. Nassim Taleb is also a big fan of Eco's anti-library concept, which I find interesting.

11. The 50th Law by 50 Cent and Robert Greene. I loved this part-bio, part-instruction manual on how to overcome fear in life and business. “Having a brush with death, or being reminded in a dramatic way of the shortness of our lives, can have a positive, therapeutic effect. Our days are numbered and so it is best to make every moment count, to have a sense of urgency about life."

12. The Spy Who Loved Me and On Her Majesty's Secret Service by Ian Fleming. Spy is the only first-person James Bond adventure, and it's told from the perspective of his lover, Vivienne Michel. I loved the 3-part structure: Me, Them, Him. 10 pages per chapter in Part 1. By 60 pages in, we know why Vivienne's come to Dreamy Pines, NY and whom she's run away from—two men who used her. The cathartic journey with Bond against a pair of mafioso is fast and fierce. Bond helps her overcome her fears to fight and not flee anymore.

13. The Woman of Samaria and Don Juan, two plays by Edmond Rostand. One motif in Rostand's plays is a deep reverence for people who act honorably, yet are often overlooked. The Woman of Samaria reimagines the biblical tale of a dishonored woman who must convince the unfriendly townsfolk to follow her to Jacob's well and see Christ with their own eyes. Second, Don Juan, which reimagines the archetypal seducer's descent toward Hell on a long staircase. A White Shade shows our anti-hero the wreckage he has caused so many women with his sexual conquests. This Shade is in fact the spirit of such heartbroken woman. She acts out of love and forgiveness in order to try and redeem him before he reaches the end of the staircase and enters Hell for eternity.

14. Mythos by Stephen Fry. During California's lockdowns, I returned to acrylic painting, something I enjoyed a lot growing up. In 2021, I spent many a Sunday afternoon or a few hours after work painting and listening to the audible version of Stephen Fry's Mythos. I have loved re-reading Edith Hamilton's Mythology since high school, but hearing Stephen Fry's rendition of the Greek gods, heroes, and antagonists was a dream.

15. The Little Bitcoin Book: Why Bitcoin Matters for Your Freedom, Finances, and Future. This 100-page, multi-authored booklet is a kind of primer on Bitcoin, highlighting various benefits: financial, cultural, personal, and political.

16. The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power, from the Freemasons to Facebook by Niall Ferguson. A dense book navigating time and space: from the modern social media platforms on all of our phones to fighting in Vietnamese jungles, creating the Italian renaissance with polymath interests, building a decentralized British empire in a then-broken world, and so much more. At the book's core I think is the showcasing of networks as inherent unstable and often causing a slow or sudden destruction of hierarchies. The scope of this book is impressive, though I would have liked a stronger conclusion of learnings from the historical examples.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

| BEST BOOKS OF 2020 Christians in Rome, moral choices amidst uncertainty, the Bitcoin standard, & more... BEST BOOKS OF 2018 Yellowstone secrets, Russian love, elephant whispering, thinking like lobsters, & more... | BEST BOOKS OF 2019 New England folklore, Gothic tales, stoic stillness, the war of art, & more... BEST BOOKS OF 2017 Idealistic roosters, US Navy SEALS, teaching Darwin in school, bad arguments & more... |