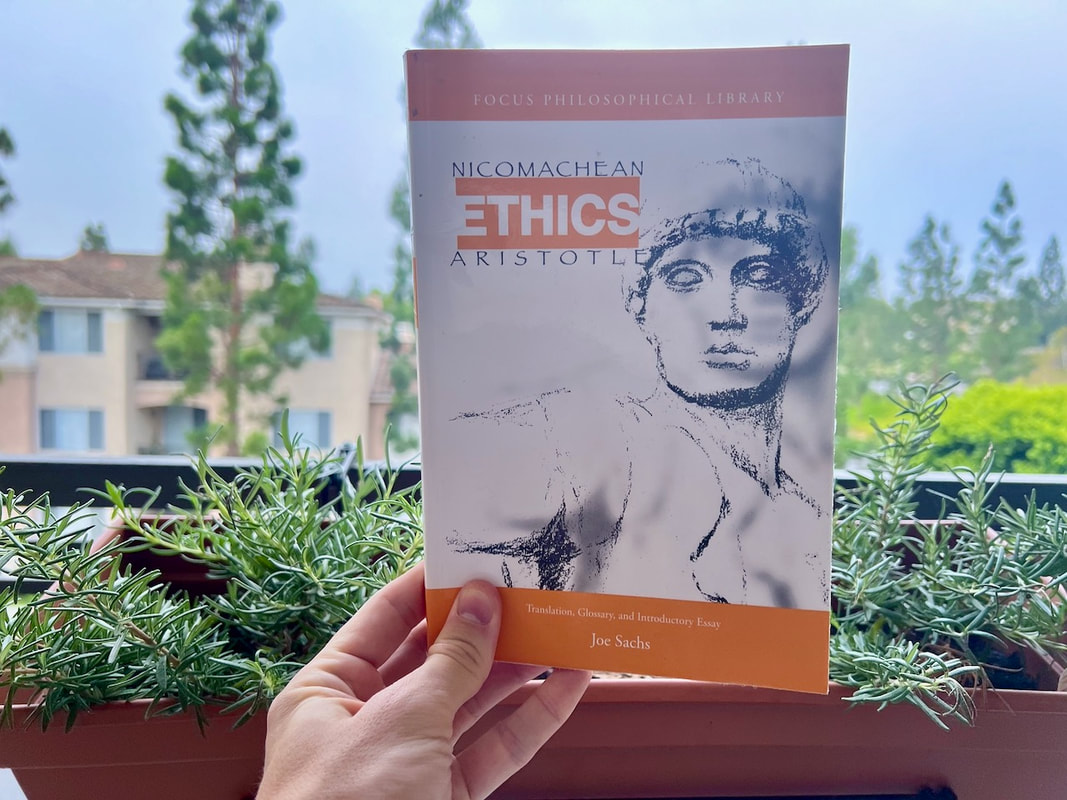

"Every art and every inquiry, and likewise every action and choice, seems to aim at some good, and hence it has been beautifully said that the good is that at which all things aim. But a certain difference is apparent among ends, since some are way of being at work, while others are certain kinds of work produced..." — Aristotle, Book I of Nicomachean Ethics

STARTING POINTS

I love the ancient Greeks and I have loved them since discovering Edith Hamilton's illustrated Mythology in 7th grade at a school book fair. The stories of Icarus, the boy who flew too close to the sun, Narcissus, the young man who fell in love with himself, and the trials of mighty Hercules enchanted me. These and many other myths were just the beginning though.

The summer before high school, I sailed the wine dark sea with Odysseus and watched the story's prequel, Troy, dozens of times. I soon encountered other stories too: Sophocles' Antigone, the original star-crossed-lovers tragedy Pyramus and Thisbe, Shakespeare's inspiration for Romeo and Juliet. I found the parallels between Oedipus and the original Star Wars saga. I sought out Disney's re-imagined versions of Hercules and Atlantis. Later, Zack Snyder's 300.

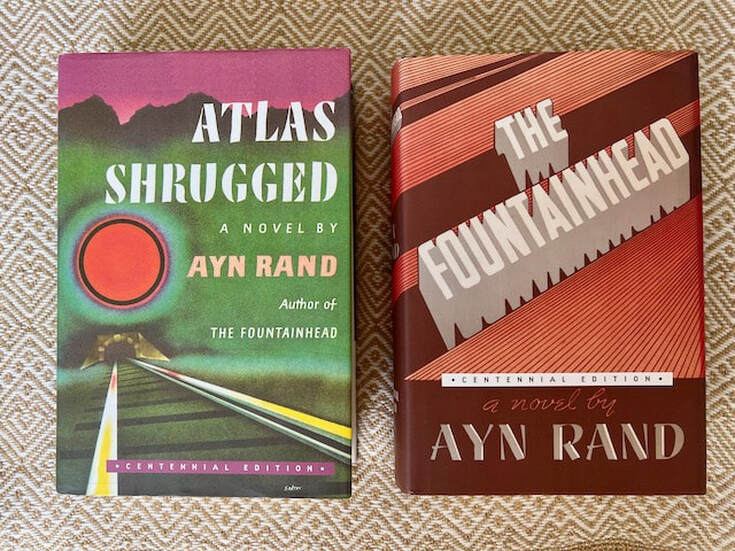

Beyond the plays and verses and myths, I also devoured historian Victor Davis Hanson's not chronological but conceptual account of the West's first civil war between Athens and Sparta—and what it can still teach us. I revisited The Tortoise and the Hare, and Aesop's other timeless fables, which I hadn't even realized came from Greece. I encountered Atlas, the titan who shouldered the earth in Ken Levine's magnum opus—and soon after Ayn Rand's. All these stories of gods and mortals, truth and beauty, right and wrong, captured me completely and continue to capture me, as they do much of the world to this day.

The summer before high school, I sailed the wine dark sea with Odysseus and watched the story's prequel, Troy, dozens of times. I soon encountered other stories too: Sophocles' Antigone, the original star-crossed-lovers tragedy Pyramus and Thisbe, Shakespeare's inspiration for Romeo and Juliet. I found the parallels between Oedipus and the original Star Wars saga. I sought out Disney's re-imagined versions of Hercules and Atlantis. Later, Zack Snyder's 300.

Beyond the plays and verses and myths, I also devoured historian Victor Davis Hanson's not chronological but conceptual account of the West's first civil war between Athens and Sparta—and what it can still teach us. I revisited The Tortoise and the Hare, and Aesop's other timeless fables, which I hadn't even realized came from Greece. I encountered Atlas, the titan who shouldered the earth in Ken Levine's magnum opus—and soon after Ayn Rand's. All these stories of gods and mortals, truth and beauty, right and wrong, captured me completely and continue to capture me, as they do much of the world to this day.

ENTER ARISTOTLE

Aristotle's Poetics was my introduction to the philosopher's works, which is an exploration into the arts. I deliberated picked it up since it was such a hot topic in Umberto Eco's spectacular novel, The Name of the Rose. The 1986 movie adaptation staring Sean Connery is also spectacular. Rose is a murder mystery set in 14th century England. Deeper, it's a philosophical battle royale between reason and faith. The Franciscan monk's Aristotelian thought process leads him to discover the truth of the murders at a monastery, based on induction (evidence) and deduction (logic). In contrast, the Catholic priests' faith leads them to blindly obey orders, like hiding evidence, burning a library containing Aristotle's original works, and killing people who dare to disobey.

THE GOOD

It's been said by some that Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics is the greatest self-help book ever written. Nicomachean is the Greek word for "victor in battle," and so while courage does count in Aristotle's ethical system as one of four major virtues (courage, justice, temperance, practical judgement), the philosopher begins with an exploration of happiness. I found his approach refreshingly down-to-earth and insightful. I'm grateful to highlight below some of the key takeaways rather than try to map out precisely his virtues, which he warns about in ethics generally.

Aristotle says that moral virtues are the means to achieving various ends—all of which are some form of good—and lead to a state of happiness. Living virtuously, he emphasizes, is to engage in an active state or condition, not hit a perfect destination and stay there, passively. Humans, he argues have a unique way of properly living:

1. Seeing an end.

2. Thinking about the means to achieve it.

3. Choosing an action or series of actions to reach it.

To engage in this uniquely human process is to live virtuously. We as humans both pursue and also experience the good, that is, if one has seen, thought through, and chosen the means and ends that are proper to a human life.

Aristotle says that moral virtues are the means to achieving various ends—all of which are some form of good—and lead to a state of happiness. Living virtuously, he emphasizes, is to engage in an active state or condition, not hit a perfect destination and stay there, passively. Humans, he argues have a unique way of properly living:

1. Seeing an end.

2. Thinking about the means to achieve it.

3. Choosing an action or series of actions to reach it.

To engage in this uniquely human process is to live virtuously. We as humans both pursue and also experience the good, that is, if one has seen, thought through, and chosen the means and ends that are proper to a human life.

THE MEANS & THE ENDS

Aristotle writes of three primary ways of life that men seem to choose over and over again: A life of pleasure, a political life, or a contemplative life. These may all exist in the same person's life, and at different life stages, but he views these three as the primary ends at which we aim. Note that when Aristotle categorizes a political life, I don't think he means engaging directly in one's government. I think here he means focusing on productive relationships with other people, primarily working a trade and building a family. This life's focus is on reputation and station in one's life, as well as achieving other externals.

The life of pleasure, Aristotle contends, is that of "fatted cattle." It is an option, but an inferior one, when considering a human's social and rational nature. A life of politics is that of pursuing honors (usually externals like wealth, reputation, and friendships). A life of contemplation, Aristotle argues is perhaps the most proper because it requires a human's unique ability to reason. This active-state of reasoning, he argues, can be the most satisfying; contemplating in the company of oneself and with others—both through reasoning speech, is the most unique to humans and perhaps the greatest source of happiness.

The life of pleasure, Aristotle contends, is that of "fatted cattle." It is an option, but an inferior one, when considering a human's social and rational nature. A life of politics is that of pursuing honors (usually externals like wealth, reputation, and friendships). A life of contemplation, Aristotle argues is perhaps the most proper because it requires a human's unique ability to reason. This active-state of reasoning, he argues, can be the most satisfying; contemplating in the company of oneself and with others—both through reasoning speech, is the most unique to humans and perhaps the greatest source of happiness.

FRIENDSHIP

My favorite virtue that Aristotle explores surprised me. He views friendship as an integrator of cities and entire civilizations. Justice, a major virtue of Aristotle's system, he argues is necessary, because not all humans are friends. In those cases between strangers or enemies, goodwill is not the default state, and requires deliberate, difficult, virtuous action to treat one another properly. I found this point very interesting, and probably true.

Aristotle contends that there are primarily three types of friendships:

1. Use: those who love one another for what is useful, and for what could come to them through the friendship.

2. Pleasure: Those who love doing things together or how one makes them feel. Charm, witty conversation, experiencing the same kind of music or food.

But these two types are "incidental," and not likely to last. The complete form of friendship is that between people who are good and are alike in virtue, "since they wish for good things for one another in the same way insofar as they are good, and they are good in themselves." In this way, "...genuine friendship" for Aristotle "becomes a measure of closeness to good character," writes the editor.

Aristotle contends that there are primarily three types of friendships:

1. Use: those who love one another for what is useful, and for what could come to them through the friendship.

2. Pleasure: Those who love doing things together or how one makes them feel. Charm, witty conversation, experiencing the same kind of music or food.

But these two types are "incidental," and not likely to last. The complete form of friendship is that between people who are good and are alike in virtue, "since they wish for good things for one another in the same way insofar as they are good, and they are good in themselves." In this way, "...genuine friendship" for Aristotle "becomes a measure of closeness to good character," writes the editor.

THREE KEY WORDS

A professor at Hillsdale College recommended to use the Joe Sachs translation, and I am so glad that I did. These three words below are crucial to understand when reading Aristotle, but often translations or interpretations skew the spirit of them:

1. HEXIS

The Greek word "Hexis" is mistranslated often as "habit," which robs the active-minded, rational process that Aristotle is identifying. This active process can in time then become integrated with his moral character, but it is not at first, if ever, a passive, thoughtless process to establish those habits. Sachs quotes from Hamlet here:

Assume a virtue if you have it not,

That monster, custom, who all sense doth eat

Of habits evil, is angel yet in this,

That to the use of actions fair and good

He likewise gives a frock or livery,

That aptly is put on. Refrain tonight,

And that shall lend a kind of easiness

To the next abstinence; the next more easy;

For use almost can change the stamp of nature...

It's not nature that needs to be changed but our own habits—with new habits.

2. ERGON

The Greek word "Ergon," is mistranslated often as "function." But this smuggles in the idea that humans serve a function and are a means to an end. Instead, Aristotle contends that a human's happiness is an end in itself and humans are not merely means to an end.

3. ENERGEIA

The Greek word "Energeia" is sometimes mistranslated as simply "activity." This, the editor contends, robs the true meaning, which is better understood as "to-be-at-work."

1. HEXIS

The Greek word "Hexis" is mistranslated often as "habit," which robs the active-minded, rational process that Aristotle is identifying. This active process can in time then become integrated with his moral character, but it is not at first, if ever, a passive, thoughtless process to establish those habits. Sachs quotes from Hamlet here:

Assume a virtue if you have it not,

That monster, custom, who all sense doth eat

Of habits evil, is angel yet in this,

That to the use of actions fair and good

He likewise gives a frock or livery,

That aptly is put on. Refrain tonight,

And that shall lend a kind of easiness

To the next abstinence; the next more easy;

For use almost can change the stamp of nature...

It's not nature that needs to be changed but our own habits—with new habits.

2. ERGON

The Greek word "Ergon," is mistranslated often as "function." But this smuggles in the idea that humans serve a function and are a means to an end. Instead, Aristotle contends that a human's happiness is an end in itself and humans are not merely means to an end.

3. ENERGEIA

The Greek word "Energeia" is sometimes mistranslated as simply "activity." This, the editor contends, robs the true meaning, which is better understood as "to-be-at-work."

TWO OTHER KEY IDEAS

1. THE MEAN

Often, Aristotle is misunderstood to advocate for a balance in all things, sometimes referred to as finding The Golden Mean. This, Translator and Editor Joe Sachs argues, is imprecise. For Aristotle, the proper mean is not purely quantitative. That is, ethical behavior is not all on a sliding scale or mapped on a spectrum. Rather, it is qualitative, and proper action is largely based on the context. There is never a singular right piece of content or quantitative measurement of ethics. "Principles are wonderful things," he writes, "but there are too many of them, and exclusive adherence to any one of them is always a vice." This is because there is an inflexibility to them if misapplied to the wrong context. So, achieving ends requires an understanding of the context in which you're operating to achieve a desired end.

2. THE NOBLE

Sachs argues that often times translators misunderstand Aristotle's view of the good and the beautiful, which is sometimes mis-appropriately wrapped in language like "noble," which could smuggle in a lofty, sense of virtue detached from happiness and one's life. "Aristotle," Sachs writes, "considers moral virtue the only practical road to effective action..." and additionally that, "[The philosopher] is always alert to the natural way that important words have more than one meaning." For example, calling something a beautiful thing could be both an esthetic judgement and an ethical one. But noble actions, properly, are not divorced from practical results. This is a major philosophical difference from his teacher, Plato.

"Greatness of soul, even from its name, seems to be concurred with great things, and let us first take up what sort of great thing they are...Now the person who seems ot be great-souled is one who considers himself worthy of great things, and is worthy of them, for one who does so not in accordance with his worth is foolish, and among those who answer to the description of virtue there is no one who is foolish..." Aristotle, Book IV of Nicomachean Ethics

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE