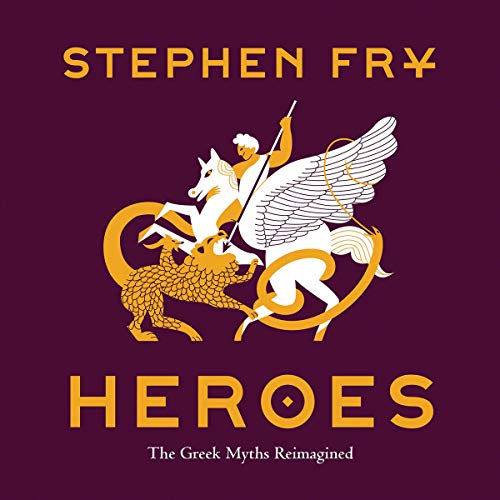

I have loved the ancient Greeks ever since discovering Edith Hamilton's illustrated Mythology at a school book fair in 7th grade. During the 2020 lockdowns I returned to many of these stories by way of actor/author/comedian Stephen Fry. His renditions of the Greek gods, heroes, and antagonists were like a long dream—one that I treasured during many an afternoon and evening painting, walking, or cooking. Mythos was first, and this summer I delved into his second, Heroes.

With extraordinary color, drama, wit, wisdom, clarity and brevity, I sailed the wine-dark sea with Perseus along his quest to kill Medusa and acquire the golden fleece. I tagged along with Heracles during his twelve trials of strength and honor. I met brave Jason, cunning Theseus, the female hunter Atalanta, the brash Bellepheron, and tragic Oedipus too.

All the while entertained by some of the greatest and oldest stories ever told, I felt and still feel so indebted to my guide, Stephen Fry, who helped me make sense of it all—the myths and monsters, the Greece language and geography, and the relevance of it all to modernity.

Carl Jung viewed myths as the dreams of mankind's collective unconsciousness. That may be true, but staying a bit closer to the Greeks, I think that their myths show a beautiful and dangerous world of order and chaos. Their heroes shed light on exotic locations, slay dangerous divine monsters, and meet their destiny—sometimes of their own choosing and sometimes on the path they take to avoid it. In doing so, the gods' powers are ultimately diminished and man's abilities grow—abilities to reason, to feel, to understand, build, survive, thrive, and wonder. [JG]

With extraordinary color, drama, wit, wisdom, clarity and brevity, I sailed the wine-dark sea with Perseus along his quest to kill Medusa and acquire the golden fleece. I tagged along with Heracles during his twelve trials of strength and honor. I met brave Jason, cunning Theseus, the female hunter Atalanta, the brash Bellepheron, and tragic Oedipus too.

All the while entertained by some of the greatest and oldest stories ever told, I felt and still feel so indebted to my guide, Stephen Fry, who helped me make sense of it all—the myths and monsters, the Greece language and geography, and the relevance of it all to modernity.

Carl Jung viewed myths as the dreams of mankind's collective unconsciousness. That may be true, but staying a bit closer to the Greeks, I think that their myths show a beautiful and dangerous world of order and chaos. Their heroes shed light on exotic locations, slay dangerous divine monsters, and meet their destiny—sometimes of their own choosing and sometimes on the path they take to avoid it. In doing so, the gods' powers are ultimately diminished and man's abilities grow—abilities to reason, to feel, to understand, build, survive, thrive, and wonder. [JG]

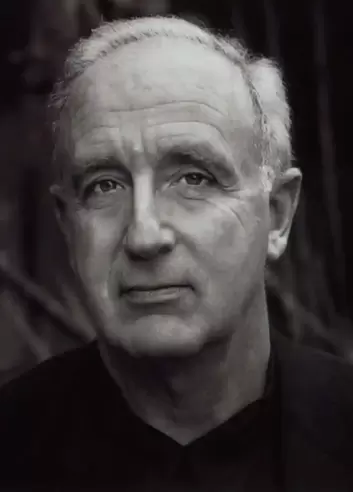

WHO IS STEPHEN FRY

Stephen Fry is a comedian, author, actor, husband, and self-declared atheist and empiricist. He is the author of a three-part Greek myths series, whose titles include Mythos, Heroes, and Troy. He is also the host of the podcast 7 Deadly Sins and an outspoken champion of free speech.

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE