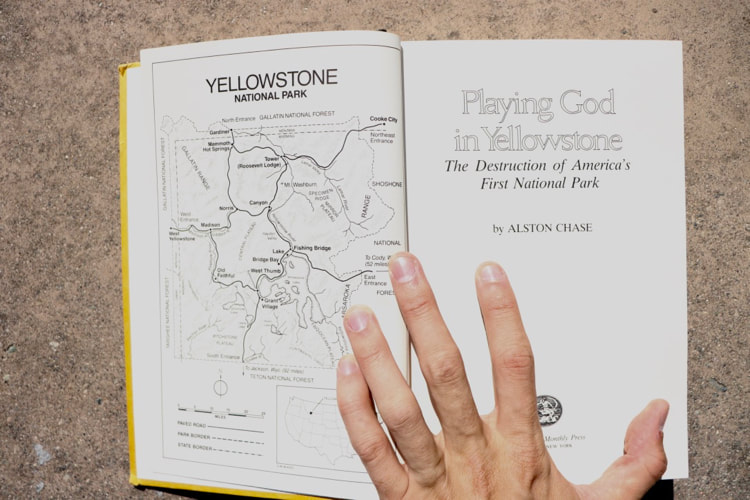

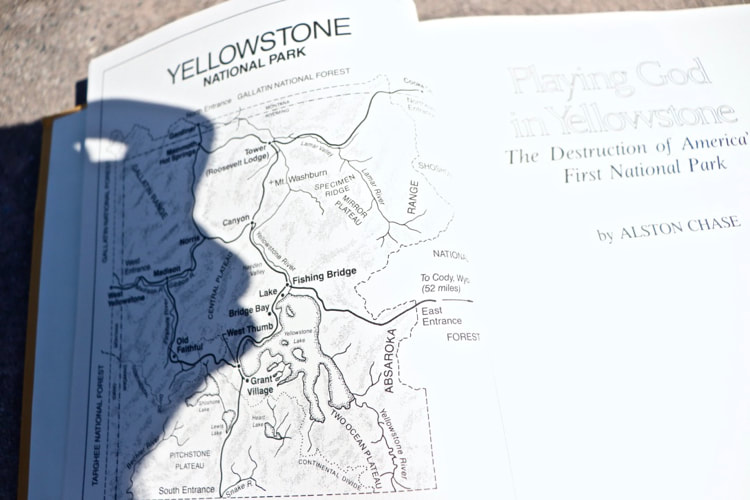

| "If Yellowstone dies its epitaph will be 'Victim of an Environmental Ideal.'" — Alston Chase, Playing God In Yellowstone: The Destruction of America's First National Park |

| IN THE BEGINNING |

In 1972, Alston and Diana Chase left their tenured academic jobs, bought a remote cabin in Montana's Smith River county, and started a summer natural-history program for kids. It was from their log cabin they had made themselves, that Chase signed a book contract promising to explore the history of Yellowstone. Having trekked most of its trails for nearly thirty years, and as a member of the Board of Directors of the Yellowstone Library and Museum Association, Chase had an intimate understanding of the park—or so he thought.

The first sign of trouble came in 1982 when he interviewed Gary Brown, the bear specialist of the park, who said, "I feel very good about the grizzly," and estimated there to be 350 grizzlies in the park. However, when Chase then left the manager and spoke with Richard Knight, the lead scientist of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team a week later, he said, "I feel very pessimistic about the grizzly," guessing that there was less than 200 in the park. How could Yellowstone's manager feel good about the grizzly, yet the scientist be worried, and both disagree so drastically about the population estimates?

"In asking this question," Chase writes, "I had set off on a search that turned out to be three years long to solve unexpected mysteries. Writing the book, rather than being an inspirational experience, turned out to be exciting, to be sure, but also disillusioning, exhausting, and sometimes dangerous." Chase's detective work was hampered at every turn by bureaucracy. "Occasionally, I found that critical records had disappeared. Freedom of Information Act requests took months to fulfill and often, when the material arrived, revealed inexplicable gaps. And though many in government and academe were eager to recount their feelings 'off the record,' most were reluctant to be quoted by name. The usual fate of whistle-blowers kept many officials silent, and the threat of losing their prerogative to study in Yellowstone frequently inhibited university scholars." (xi)

The first sign of trouble came in 1982 when he interviewed Gary Brown, the bear specialist of the park, who said, "I feel very good about the grizzly," and estimated there to be 350 grizzlies in the park. However, when Chase then left the manager and spoke with Richard Knight, the lead scientist of the Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team a week later, he said, "I feel very pessimistic about the grizzly," guessing that there was less than 200 in the park. How could Yellowstone's manager feel good about the grizzly, yet the scientist be worried, and both disagree so drastically about the population estimates?

"In asking this question," Chase writes, "I had set off on a search that turned out to be three years long to solve unexpected mysteries. Writing the book, rather than being an inspirational experience, turned out to be exciting, to be sure, but also disillusioning, exhausting, and sometimes dangerous." Chase's detective work was hampered at every turn by bureaucracy. "Occasionally, I found that critical records had disappeared. Freedom of Information Act requests took months to fulfill and often, when the material arrived, revealed inexplicable gaps. And though many in government and academe were eager to recount their feelings 'off the record,' most were reluctant to be quoted by name. The usual fate of whistle-blowers kept many officials silent, and the threat of losing their prerogative to study in Yellowstone frequently inhibited university scholars." (xi)

| A GADFLY IN THE GARDEN OF EDEN |

Instead of a thriving example of American ingenuity, idealism, and scientific policy, Yellowstone, Chase argues is dying. The culprit? Tragically, our own National Park Service, whose century of mismanagement has destroyed the flora and fauna. Their law of the land, steeped in the idea of natural regulation, is largely to blame, based on virtually no scientific research, and concocted in the '50s and '60s from an ironic, lethal dosage of hubris.

In Playing God, Alston Chase:

And, most importantly, Chase lays a trail of breadcrumbs leading toward a better environment, one found by asking simple, yet profound questions:

It's this type of Socratic dialogue, that Chase injects into an all-too political, dogmatic landscape, and the effect is still so damn refreshing thirty years later. In a three-part talk he gave in the '90s. "Stewardship vs. Biocentrism," which explores many ideas of Playing God in Yellowstone, Chase begins by recounting a famous story of Socrates, the philosopher:

One day, Socrates' friend, Chaerephon, went to the Oracle of Athens and asked, "Who is the wisest person in Athens?" The Oracle replied, "Socrates." Chaerephon told his friend, who was deeply disturbed, because he was convinced he knew nothing at all. After several sleepless nights, the man emerged from his home, believing he now understood what the Oracle had meant: that everyone else knew nothing either, but that they thought they knew a great deal. Socrates, conversely, knew that he knew nothing; he was the wisest because he was aware of his own ignorance. And so, the wisest man took to Athens' streets, asking strangers series of questions from morning to night: What is truth? What is virtue? What is beauty? And, by engaging in a dialogue brought a much-needed, humbling dosage of self-awareness to the people of Athens whose answers often easily unwound.

Socrates likened his role in society to that of a gadfly, a small insect that buzzes around horses and cows biting them, often swatted by the animals' tails. In dialogue, Socrates' patients often grew dizzy and frustrated too, lashing out at him instead of themselves. "Ultimately, they gave him the ultimate swat, by making him drink the Hemlock." If you look up gadfly in the college dictionary, it's defined as 'a constructive critic of established institutions.' "To that," Chase said, looking up proudly at the audience, "I plead guilty." [JG]

In Playing God, Alston Chase:

- Documents the holocaust of wildlife perpetrated by Yellowstone's policies (grizzlies, black bears, wolves, elk, bison, beavers, and others)

- Explores the counter-intuitive value of controlled forest fires in order to grow forests

- Documents Yellowstone's institutionalized discrimination of scientists and enshrinement of a police/ranger force

- Observes the intellectual ingredients of the environmentalist stew of the '60s, cherry-picked from "Buddhism, Tao, Russian mystics, pre-Socratic, romantic poets, Indians...pessimistic German philosophers" and others

And, most importantly, Chase lays a trail of breadcrumbs leading toward a better environment, one found by asking simple, yet profound questions:

- What is nature?

- Is man separate from nature or an integral part of it?

- What is an ecosystem?

- Can man affect an ecosystem for the better or is it always for the worse?

- Is there an inherent value in anything and everything?

- How would we know this?

It's this type of Socratic dialogue, that Chase injects into an all-too political, dogmatic landscape, and the effect is still so damn refreshing thirty years later. In a three-part talk he gave in the '90s. "Stewardship vs. Biocentrism," which explores many ideas of Playing God in Yellowstone, Chase begins by recounting a famous story of Socrates, the philosopher:

One day, Socrates' friend, Chaerephon, went to the Oracle of Athens and asked, "Who is the wisest person in Athens?" The Oracle replied, "Socrates." Chaerephon told his friend, who was deeply disturbed, because he was convinced he knew nothing at all. After several sleepless nights, the man emerged from his home, believing he now understood what the Oracle had meant: that everyone else knew nothing either, but that they thought they knew a great deal. Socrates, conversely, knew that he knew nothing; he was the wisest because he was aware of his own ignorance. And so, the wisest man took to Athens' streets, asking strangers series of questions from morning to night: What is truth? What is virtue? What is beauty? And, by engaging in a dialogue brought a much-needed, humbling dosage of self-awareness to the people of Athens whose answers often easily unwound.

Socrates likened his role in society to that of a gadfly, a small insect that buzzes around horses and cows biting them, often swatted by the animals' tails. In dialogue, Socrates' patients often grew dizzy and frustrated too, lashing out at him instead of themselves. "Ultimately, they gave him the ultimate swat, by making him drink the Hemlock." If you look up gadfly in the college dictionary, it's defined as 'a constructive critic of established institutions.' "To that," Chase said, looking up proudly at the audience, "I plead guilty." [JG]

QUOTES I PONDERED

16. "When the search for truth is confused with political advocacy, the pursuit of knowledge is reduced to the quest for power." — Alston Chase

15. "For the benefit and enjoyment of the people—Yellowstone National park, created by an act of Congress, March 1 1872." — Inscription on the Roosevelt Arch in Yellowstone

14. "Religions are born and may die, but superstition is immortal." — Will and Ariel Durant

13. "Our national parks are outdoor museums, yet they are run by policemen, not by historians or scientists." — Senior Official to Alston Chase

12. "Natural regulation, dressed in the trappings of biological theory, gave policy the patina of academic respectability while real science was carefully prohibited."

11. "In the environmentalists' scheme of things, however, man can stand apart from nature, and when he does he often commits the worst sin of all, the sin the ancient Greeks called hubris—usurping the role of God. By playing God he stands apart and thereby does evil. Yet they also seem to suggest that human beings should stand apart from nature as well. For the ethic of protectionism was nothing more than protecting nature from man." [Emphasis mine.]

10. "All conservatism is based upon the idea that if you leave things alone you them as they are. But you do not. If you leave a thing alone you leave it to a torrent of chance." — G. K. Chesterton

9. "This reserve is a natural breeding ground and nursery for those stately and beautiful haunters of the wilds which have now vanished from so many of the great forests, the vast lonely plains, and the high mountain rays, where they once abounded...Surely, our people do not understand even yet the rich heritage that is theirs...our people should see to it that they are preserved for their children and their children's children forever, with their majestic beauty all unmarred." — Theodore Roosevelt

8. "Yet, this prized land, reflecting our highest ideals of natural preservation, protected for a century, is not what is appears to be. Rather than a place where time stands still, it is caught in a river of change. Rather than preserved, it is being destroyed."

7. "For more than a century the faith of environmental activists had been coalescing around a collection of ideas implying rejection: rejection of Judeo-Christianity, traditional science, technology, and civilization. In the void created by this iconoclasm they had assembled a jumble of ideas picked up from all over the world: from Buddhism, Tao, Russian mystics, pre-Socratic, romantic poets, Indians, and pessimistic German philosophers. And although each believer followed his own star, a family resemblance connected their ideas. Many quietly called themselves pantheists, espousing the view that all things were connected and sacred. They urged noninterference with spiritual nature. But they were still not sure now nature was to be known, and what was to be the place of human beings in the scheme of things."

6. "Every age is fed on illusions." — Joseph Conrad

5. "The environmental awakening, however, made the public less tolerant of the policy of direct reductions, not more so. For Rachel Carson, Paul Ehrlich, Barry Commoner, and others taught that nature's problems were caused by humanity. The way we lived, grew food, drank water, dumped sewage, built houses, drove cars, was destroying the earth. And the silent victims of our greed and waste were than dumb and innocent animals of the world; the peregrine falcons and bald eagles poisoned by DDT, the whales and seals harpooned and clubbed for profit, the plankton and fishes of the sea smothered by oil from tanks, the jaguars, cheetahs, and ocelots skinned for high fashion, the countless species disappearing every day as the world's forests were stripped here by hungry souls chopping trees for farms and firewood."

4. "As a consequence, the new definition of wilderness [by the Wilderness Act of 1964], ('an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man'), replaced science with romance. Ecosystems management—managing a park as a "vignette of primitive America," as stated in the Leopold Report—was an idea that came a hundred years too late. Yet the myth it presupposed—that man was not a part of nature—would be sustained."

3. "You can not step twice into the same river." — Heraclitus

2. "The elk problem could not be defined out of existence. Difficulties, like the elk themselves, quietly multiplied."

1. "Fire improves nature in many ways. It changes the chemical composition of the soil, promoting more varied vegetation and supporting more diverse wildlife. It releases soluble mineral salts in plant tissue, and increases the nitrogen, calcium, potassium, and phosphorous in the soil that act as fertilizers. It decreases soil acid rain, not only in the earth but in the streams and lakes as well. It blackens the ground, permitting more of the sun's heart to warm it and promoting faster growth of vegetation. Burning forests stimulates germination in some trees, such as lodgepole pine; it produces habitat for nesting birds, such as the mountain bluebird. But the most important result of burning is that is arrests or reverses the normally inexorable seral succession."

15. "For the benefit and enjoyment of the people—Yellowstone National park, created by an act of Congress, March 1 1872." — Inscription on the Roosevelt Arch in Yellowstone

14. "Religions are born and may die, but superstition is immortal." — Will and Ariel Durant

13. "Our national parks are outdoor museums, yet they are run by policemen, not by historians or scientists." — Senior Official to Alston Chase

12. "Natural regulation, dressed in the trappings of biological theory, gave policy the patina of academic respectability while real science was carefully prohibited."

11. "In the environmentalists' scheme of things, however, man can stand apart from nature, and when he does he often commits the worst sin of all, the sin the ancient Greeks called hubris—usurping the role of God. By playing God he stands apart and thereby does evil. Yet they also seem to suggest that human beings should stand apart from nature as well. For the ethic of protectionism was nothing more than protecting nature from man." [Emphasis mine.]

10. "All conservatism is based upon the idea that if you leave things alone you them as they are. But you do not. If you leave a thing alone you leave it to a torrent of chance." — G. K. Chesterton

9. "This reserve is a natural breeding ground and nursery for those stately and beautiful haunters of the wilds which have now vanished from so many of the great forests, the vast lonely plains, and the high mountain rays, where they once abounded...Surely, our people do not understand even yet the rich heritage that is theirs...our people should see to it that they are preserved for their children and their children's children forever, with their majestic beauty all unmarred." — Theodore Roosevelt

8. "Yet, this prized land, reflecting our highest ideals of natural preservation, protected for a century, is not what is appears to be. Rather than a place where time stands still, it is caught in a river of change. Rather than preserved, it is being destroyed."

7. "For more than a century the faith of environmental activists had been coalescing around a collection of ideas implying rejection: rejection of Judeo-Christianity, traditional science, technology, and civilization. In the void created by this iconoclasm they had assembled a jumble of ideas picked up from all over the world: from Buddhism, Tao, Russian mystics, pre-Socratic, romantic poets, Indians, and pessimistic German philosophers. And although each believer followed his own star, a family resemblance connected their ideas. Many quietly called themselves pantheists, espousing the view that all things were connected and sacred. They urged noninterference with spiritual nature. But they were still not sure now nature was to be known, and what was to be the place of human beings in the scheme of things."

6. "Every age is fed on illusions." — Joseph Conrad

5. "The environmental awakening, however, made the public less tolerant of the policy of direct reductions, not more so. For Rachel Carson, Paul Ehrlich, Barry Commoner, and others taught that nature's problems were caused by humanity. The way we lived, grew food, drank water, dumped sewage, built houses, drove cars, was destroying the earth. And the silent victims of our greed and waste were than dumb and innocent animals of the world; the peregrine falcons and bald eagles poisoned by DDT, the whales and seals harpooned and clubbed for profit, the plankton and fishes of the sea smothered by oil from tanks, the jaguars, cheetahs, and ocelots skinned for high fashion, the countless species disappearing every day as the world's forests were stripped here by hungry souls chopping trees for farms and firewood."

4. "As a consequence, the new definition of wilderness [by the Wilderness Act of 1964], ('an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man'), replaced science with romance. Ecosystems management—managing a park as a "vignette of primitive America," as stated in the Leopold Report—was an idea that came a hundred years too late. Yet the myth it presupposed—that man was not a part of nature—would be sustained."

3. "You can not step twice into the same river." — Heraclitus

2. "The elk problem could not be defined out of existence. Difficulties, like the elk themselves, quietly multiplied."

1. "Fire improves nature in many ways. It changes the chemical composition of the soil, promoting more varied vegetation and supporting more diverse wildlife. It releases soluble mineral salts in plant tissue, and increases the nitrogen, calcium, potassium, and phosphorous in the soil that act as fertilizers. It decreases soil acid rain, not only in the earth but in the streams and lakes as well. It blackens the ground, permitting more of the sun's heart to warm it and promoting faster growth of vegetation. Burning forests stimulates germination in some trees, such as lodgepole pine; it produces habitat for nesting birds, such as the mountain bluebird. But the most important result of burning is that is arrests or reverses the normally inexorable seral succession."

WHO IS ALSTON CHASE?

| Alston Chase is a former philosopher professor and the author of four books, including Playing God in Yellowstone: The Destruction of America's First National Park, In a Dark Wood: The Fight Over Forest and the Rising Tyranny of Ecology, and A Mind For Murder which explores the Unibomber's education and radicalization at Harvard University. Chase lives in Paradise Valley, Montana. |

| "I was to learn later in life that we tend to meet any new situation by reorganizing...and a wonderful method it can be for creating inefficiency and demoralization." — Petronius, died A.D. 66 |

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE