On August 15th, 1805, nearly two hundred and ten years ago to the day, a young aristocrat from Caracas climbed Italy's Mount Palatino. He shared the trek with his two best friends, one of whom was recounting a previous journey up the mountain one millennium earlier, in 494 B.C. by Roman plebeians. The plebeians did so in order to confront a tyrannical patrician ruler, voicing threats of secession from the empire. Perhaps inspired by his friend's tale of ancient freedom fighters, the young man cast aside the sting in his legs and finally reached the summit, and a slab of white marble atop it. Then, the young man wrote, "we all knelt down, embraced, and swore that we would liberate our country or die trying."

Fourteen years later, the young man did.

Simon Bolivar was the George Washington of South America. His life's battle against monarchical Spain for the soul of the (southern) New World is one of the most harrowing and inspiring stories I've come across in years. Marie Arana's biography of El Libertador is a treasure, one that I left with a sense of bittersweet nostalgia. Bolivar's idealism, passion, and purpose is so grand that I feel cheated by public education, having never once heard his name in dozens of history classes.

Fourteen years later, the young man did.

Simon Bolivar was the George Washington of South America. His life's battle against monarchical Spain for the soul of the (southern) New World is one of the most harrowing and inspiring stories I've come across in years. Marie Arana's biography of El Libertador is a treasure, one that I left with a sense of bittersweet nostalgia. Bolivar's idealism, passion, and purpose is so grand that I feel cheated by public education, having never once heard his name in dozens of history classes.

Though his flaws as a political leader damaged much of his life's project, Bolivar's dogged commitment to freedom, and mastery of military strategy, ended 300 years of Spanish oppression, and replaced it with The United States of South America, a confederation of free republics, if only for a time. It Included Bolivia, Venezuela, Peru, Chile, Panama and what was then New Granada. Bolivar's vision for a free New World was in some areas more enlightened than his North American neighbors. Universal suffrage and the complete abolition of slavery were primary concerns for Bolivar from the outset, which he incorporated into his constitution, though his lesser corroborators would ultimately compromise on.

“I have come to decree as law full liberty to all slaves who have trembled under the Spanish yoke for three centuries.” |

To understand Bolivar's lifelong commitment to his Enlightenment ideals of freedom and deep hatred for Spain, the author Marie Arana explores the young aristocrat's childhood in great length, which was a torrential mixture of privilege and tragedy. Losing both of his parents before his teenage years, Bolivar was tutored by Simon Rodriguez, an anti-monarchical, anti-religious free thinker. Rodriguez instructed the boy in literature, accounting, history, philosophy, and fencing, but always aimed to do so by exiting the classroom, putting down the books, and exciting the senses. It's interesting that Rodriquez's favorite book was Rousseaeu's Emile, the story of an orphan whose classroom was nature itself. Under Rodriguez's instruction, Bolivar developed a profound admiration for the French philosopher Voltaire, as well as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Looking back, Bolivar said this with regard to his blossoming awareness of liberty and tyranny:

“From boyhood I thought of little else: I was fascinated by stories of Greek and Roman heroes. The revolution of the United States had just taken place and it, too, was an example. Washington awoke in me a desire to be just like him…When I and my two companions…arrived in Rome, we climbed Mount Palatino, and we all knelt down, embraced, and swore that we would liberate our country or die trying.” |

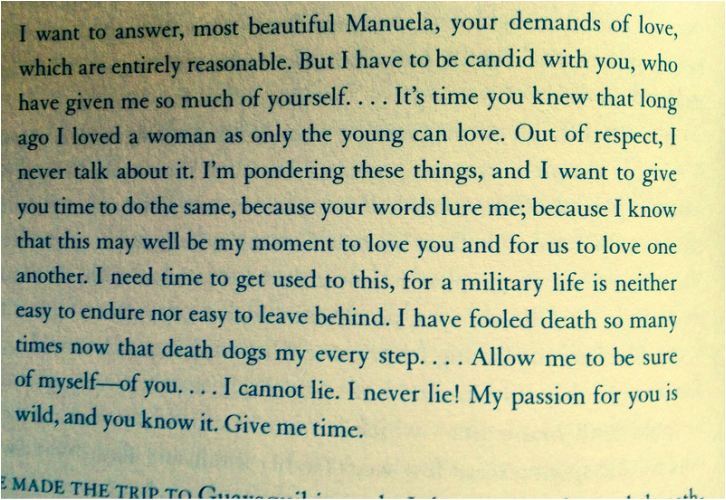

I think it's important to note that Bolivar's oath to end Spain's enslavement of the New World {propagated by king and priest alike} atop Mount Palatino came after a life-changing event: the death of his bride. They'd been married only five months, he eighteen and she, twenty-one, "before Heaven took her" from Bolivar by way of Yellow Fever. He swore never to remarry, and never would. El Liberator did however initiate many passionate affairs over his life, including one with Manuela Saenz, a famous libertine in Venezuela. Manuela would save her lover from two assassination attempts, winning legendary status as 'The Liberatrix of the Liberator'. I found this letter from Bolivar to Manuela revealing of the couple, both as freedom-fighters and the romantics:

She did.

And in that time, he drove Spain and its 300 years of slavery and oppression back to the Old World. New enemies arose from once-friends, but never Simon or Manuela waver in their commitment to one another.

I can't recommend Marie Arana's biography of El Liberator enough. If you're looking for adventure, romance, and inspiration as I always am, this one will do!

Here is an awesome trailer for it.

And in that time, he drove Spain and its 300 years of slavery and oppression back to the Old World. New enemies arose from once-friends, but never Simon or Manuela waver in their commitment to one another.

I can't recommend Marie Arana's biography of El Liberator enough. If you're looking for adventure, romance, and inspiration as I always am, this one will do!

Here is an awesome trailer for it.