When I was seven, I fell in love with The Adventures of Robin Hood — for its heroes and villains, dangerous action and romance, and the mythical world it all happened in. Even beforehand though, my parents had impressed upon me the importance of asking certain questions: What is right and wrong? What is the meaning of life? What should I do? — and this story helped me to explore them in an accessible way, one much more real and enjoyable than Sunday church sermons. What would Robin Hood do? I would ask myself, and then try to find an answer from there.

I loved the stories with all of their sword fighting, and horseback riding, and chandelier-swinging, but because it added up to something: heroism — a version that was fun to enjoy in the moment and think about later as guidelines for how to deal with things in my own world. I never stole from the rich and gave to the poor — I think stealing in any form is the antithesis of heroism — but I did fight two bullies in school one day at recess when they wouldn't stop picking on the kid in the wheelchair. The Principal wasn't happy with me, but my Dad was. I'd like to think Robin Hood would have been too.

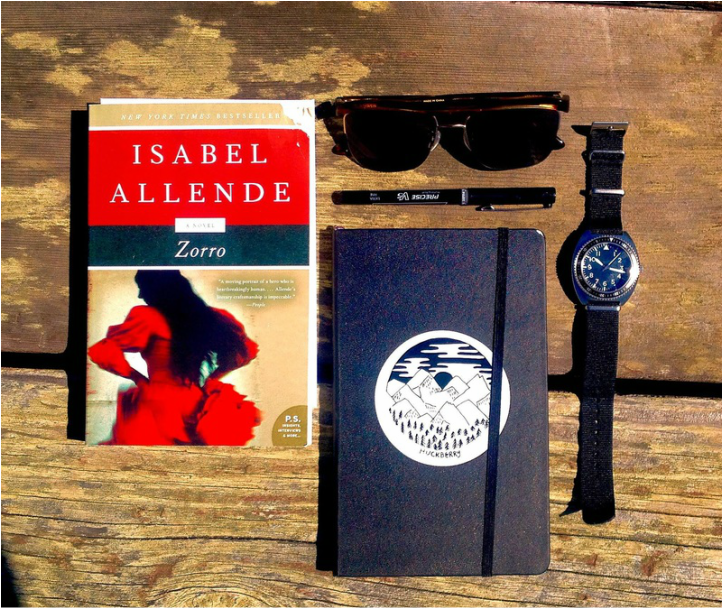

Fast forward almost twenty years. I watch The Mask of Zorro with Anthony Hopkins, Antonio Banderas, and Catherine Zeta-Jones for the first time. Immediately, I'm transported away to Old California, a sort of mythical America in which a corrupt Spanish government preys on its citizens. Here, justice must wear a mask because it is illegal. I've watched it many times since, but decided I needed to look into the source material. I was not disappointed.

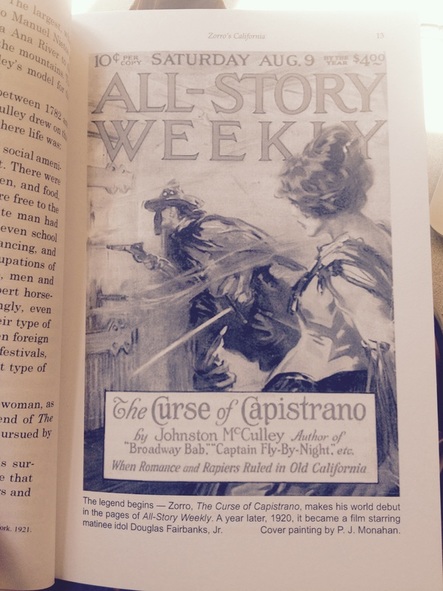

In 1919, Johnston McCulley first introduced the world to this masked avenger in his weekly serial, The Curse of Capistrano. Zorro is a distinctly American superhero. Don't get me wrong, I still love Robin Hood, but Zorro takes the cake for me.

I loved the stories with all of their sword fighting, and horseback riding, and chandelier-swinging, but because it added up to something: heroism — a version that was fun to enjoy in the moment and think about later as guidelines for how to deal with things in my own world. I never stole from the rich and gave to the poor — I think stealing in any form is the antithesis of heroism — but I did fight two bullies in school one day at recess when they wouldn't stop picking on the kid in the wheelchair. The Principal wasn't happy with me, but my Dad was. I'd like to think Robin Hood would have been too.

Fast forward almost twenty years. I watch The Mask of Zorro with Anthony Hopkins, Antonio Banderas, and Catherine Zeta-Jones for the first time. Immediately, I'm transported away to Old California, a sort of mythical America in which a corrupt Spanish government preys on its citizens. Here, justice must wear a mask because it is illegal. I've watched it many times since, but decided I needed to look into the source material. I was not disappointed.

In 1919, Johnston McCulley first introduced the world to this masked avenger in his weekly serial, The Curse of Capistrano. Zorro is a distinctly American superhero. Don't get me wrong, I still love Robin Hood, but Zorro takes the cake for me.

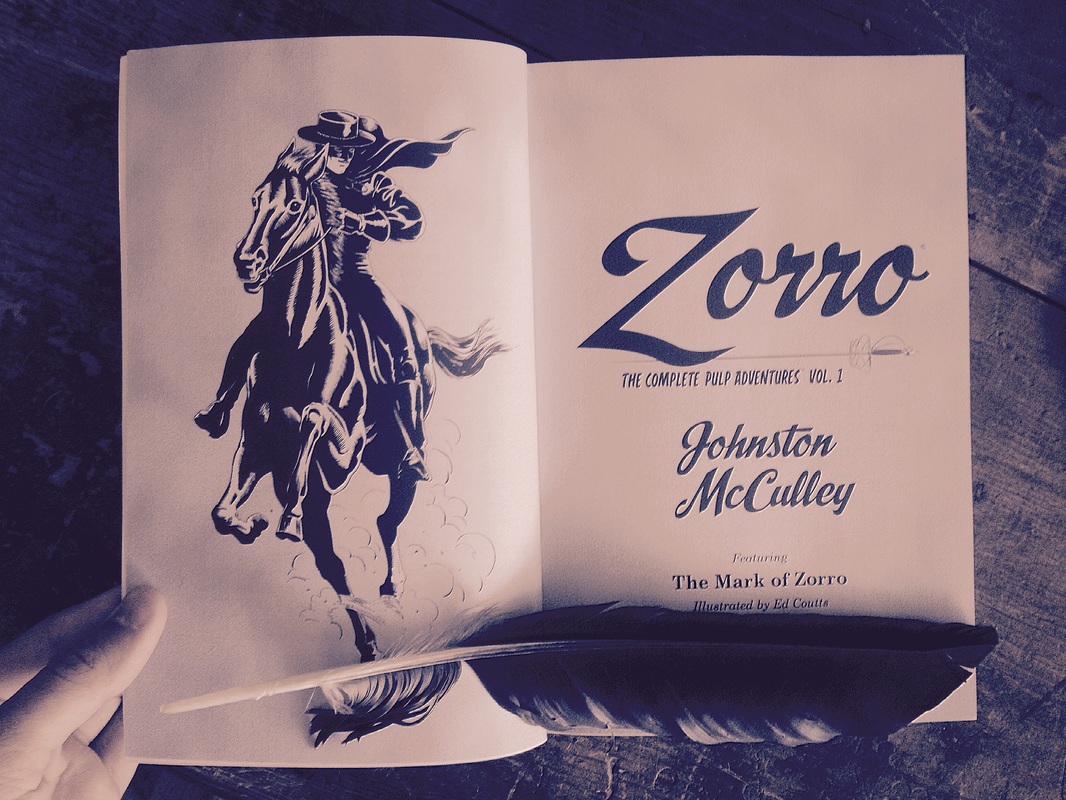

In Zorro: The Complete Pulp Adventures we meet Pedro Gonzalez, a power-lusting Sergeant in the Spanish army who's stationed in occupied California. He's with a few of his lower ranking soldiers at the town's saloon, drinking himself into a rage over the 'pretty highwayman,' Zorro, who he claims has been 'terrorizing' the main road between Los Angeles and San Francisco. The Sergeant's reports know that Zorro is not a thief or pirate and only targets those who hurt the indigenous peoples and citizens, but they decide not to correct their drunk superior officer.

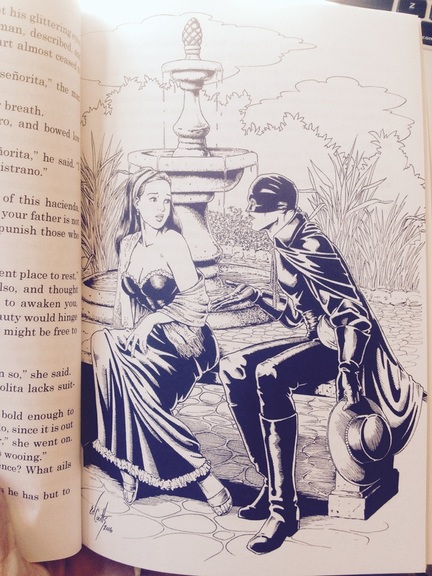

Reaching a climax of rage, Sergeant Gonzalez swears to uncover the identity of the masked Zorro, and wishes he would walk into the saloon right now so he could run his blade through his heart. As if on command, the door swings open... {END CHAPTER 1} ... and {START CHAPTER 2} ... Don Diego Vega enters. The handsome twenty-four year-old is the son of a local self-made merchant, who owns many vineyards. Business has brought Diego to the saloon, but the young man is sure to defend Zorro, at least casually, from Gonzalez's boisterous smears. Then he leaves, but soon after the door swings open again, this time revealing a man cloaked in black, and wearing a mask... {END CHAPTER 2} ... and {START CHAPTER 3} ... It's Zorro.

I adore this kind of story. The melodramatic cliff-hangers at the end of each chapter, the relentlessly paced building of tension and conflict, the characterization through action. It's a pulp serial adventure, but it's more appetizing and rewarding to read — at least for me — than most books that come out today — ones with weak characters, no coherent plot, and way too much focus on depravity.

Reaching a climax of rage, Sergeant Gonzalez swears to uncover the identity of the masked Zorro, and wishes he would walk into the saloon right now so he could run his blade through his heart. As if on command, the door swings open... {END CHAPTER 1} ... and {START CHAPTER 2} ... Don Diego Vega enters. The handsome twenty-four year-old is the son of a local self-made merchant, who owns many vineyards. Business has brought Diego to the saloon, but the young man is sure to defend Zorro, at least casually, from Gonzalez's boisterous smears. Then he leaves, but soon after the door swings open again, this time revealing a man cloaked in black, and wearing a mask... {END CHAPTER 2} ... and {START CHAPTER 3} ... It's Zorro.

I adore this kind of story. The melodramatic cliff-hangers at the end of each chapter, the relentlessly paced building of tension and conflict, the characterization through action. It's a pulp serial adventure, but it's more appetizing and rewarding to read — at least for me — than most books that come out today — ones with weak characters, no coherent plot, and way too much focus on depravity.

Zorro is a man of action; confident, morally righteous, and sexual — he's an eccentric, and self-aware of this fact. He loves to humiliate evil as much as he loves defeating it. He loves women — and one in particular, but he's unapologetically a flirt. He's cerebral; a trickster (Zorro is Spanish for 'fox') who must hide and choose his fights very tactfully. When I measure him against Robin of Locksley, the English outlaw ends up feeling a bit colder, a bit more lifeless, and somewhat of a prude. There's a boldness, almost an arrogance, that Zorro exudes. In part, yes, he's playing the hero publicly, but he's not just playing dress up. It's a way for Don Diego Vega, the handsome twenty-four-year-old, to buck all of tradition, and step into his own reality where he is the master — defeating evil, getting his woman, and being a truly good man. If you ever want to get lost for an afternoon and see a glimpse of heroism check out Zorro. It'll make you feel like a kid again — and that's a truly good thing. Long live the Fox. {JG}