"I suspect that you underestimate the strength and depth of feeling against industrial civilization that has been developing in recent years. I've been surprised at some of the things people have written [to me in jail]."

— Ted Kaczynski, 1998, quoted in Alston Chase's Harvard and the Unabomber

Between 1978 and 1995, Harvard-graduate and former math professor, Ted Kaczynski, mailed or planted a series of increasingly sophisticated homemade bombs to science labs and government offices across the USA. All told, he killed 3 people and injured 23 others. 16 bombs were ultimately attributed to him. His 35,000 word manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future, was published in part by The Washington Post and The New York Times in 1995 under the promise of him "desisting" from future bombings. A writer of The New Yorker called the manifesto a "carefully reasoned, artfully written paper..." The manhunt for Kaczynski, then known only as "the Unabomber," was the longest and most expensive in FBI history. It probably would have continued for years—as would have the bombing, but came to an end when Kaczynski's brother shared his whereabouts with law enforcement: a remote cabin in Montana. Inside were various pipe bombs waiting for postage, bookshelves of philosophy, literature, and diaries written in secret code, and an unkempt hermit-like psychopath.

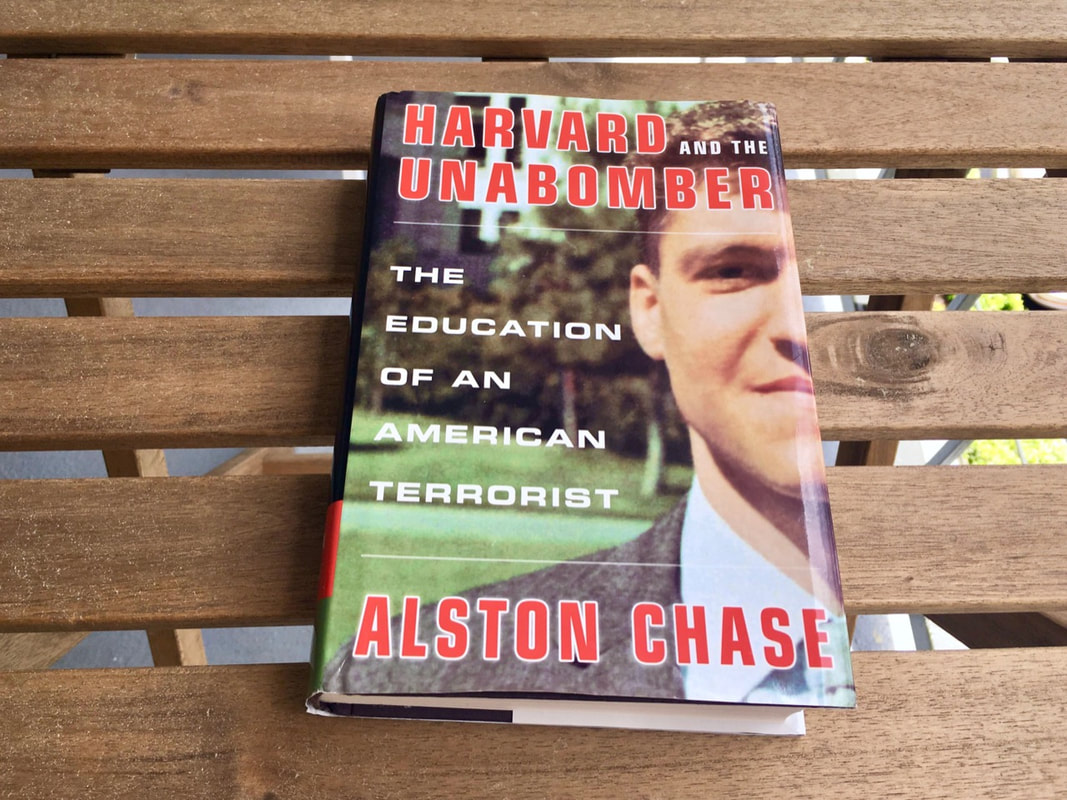

In Harvard and the Unabomber (2003) author Alston Chase offers an exhaustively researched and distinctively new interpretation of the America's worst homegrown terrorist. Far from being a deranged, lustful serial killer or a radical Luddite as the media portrayed him, Chase argues that Kaczynski embodied the ideas and psychology of the Silent Generation of the '50s and, ultimately, the activism of the counter-cultural '60s. Kaczynski was radically average; his future actions chillingly mirrored the intellectual diet of his Harvard education and the isolation felt by young, bright minds of the 20th century. Upon examination of the student life at Harvard—and America en masse—Chase finds a dangerous concoction for anti-technological and morally neutral sentiments on campuses. As the Cold War raged, "General Education [courses] delivered," Chase writes, "a double whammy of pessimism. From humanists we learned that science threatens civilization. From the scientists we learned that science cannot be stopped. Taken together, they implied there is no hope. Gen Ed had created what would become a permanent fixture at Harvard, and indeed throughout academe: the culture of despair." This despair included moral subjectivism, summed up in then-Harvard President, Derek Bok's view that "ethical neutrality is the guiding rule for the historian or scholar."

Perhaps, worst of all, Kaczyinski's manifesto was read sympathetically by radical environmentalists and Marxist professors, yes, but also by many Americans concerned about swift technological progress and growing government control. "The Unabomber episode...is a demonstration of how ill prepared modern society is for new, unfamiliar confrontations...the awkward denials and embarrassed cringing...all flow from a central fear that modernity is not up to the argument [to refute Kaczynski]," Chase writes. If Kaczynski's views have sympathy, do his methods? For anarchists and anti-globalists who write him in prison and eco-saboteurs and terrorists of the 21st century, yes. What say the rest of us? It's tragically too quiet, and as Chase shows through Kaczynski's upbringing and Ivy League education, ideas—and the lack of good ones--have consequences. [JG]

In Harvard and the Unabomber (2003) author Alston Chase offers an exhaustively researched and distinctively new interpretation of the America's worst homegrown terrorist. Far from being a deranged, lustful serial killer or a radical Luddite as the media portrayed him, Chase argues that Kaczynski embodied the ideas and psychology of the Silent Generation of the '50s and, ultimately, the activism of the counter-cultural '60s. Kaczynski was radically average; his future actions chillingly mirrored the intellectual diet of his Harvard education and the isolation felt by young, bright minds of the 20th century. Upon examination of the student life at Harvard—and America en masse—Chase finds a dangerous concoction for anti-technological and morally neutral sentiments on campuses. As the Cold War raged, "General Education [courses] delivered," Chase writes, "a double whammy of pessimism. From humanists we learned that science threatens civilization. From the scientists we learned that science cannot be stopped. Taken together, they implied there is no hope. Gen Ed had created what would become a permanent fixture at Harvard, and indeed throughout academe: the culture of despair." This despair included moral subjectivism, summed up in then-Harvard President, Derek Bok's view that "ethical neutrality is the guiding rule for the historian or scholar."

Perhaps, worst of all, Kaczyinski's manifesto was read sympathetically by radical environmentalists and Marxist professors, yes, but also by many Americans concerned about swift technological progress and growing government control. "The Unabomber episode...is a demonstration of how ill prepared modern society is for new, unfamiliar confrontations...the awkward denials and embarrassed cringing...all flow from a central fear that modernity is not up to the argument [to refute Kaczynski]," Chase writes. If Kaczynski's views have sympathy, do his methods? For anarchists and anti-globalists who write him in prison and eco-saboteurs and terrorists of the 21st century, yes. What say the rest of us? It's tragically too quiet, and as Chase shows through Kaczynski's upbringing and Ivy League education, ideas—and the lack of good ones--have consequences. [JG]

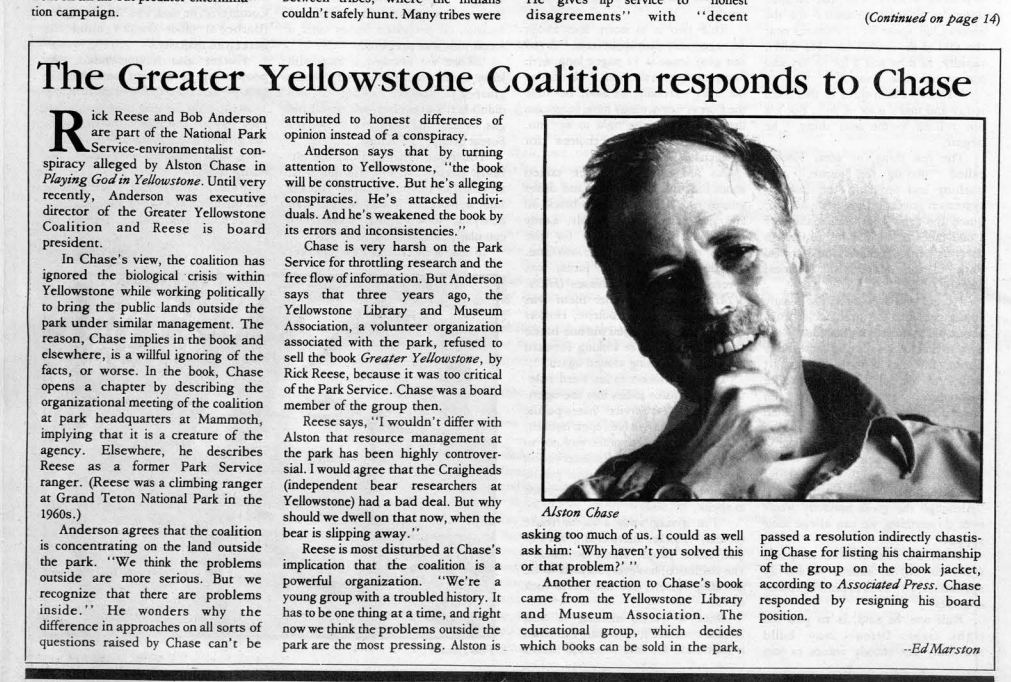

WHO IS ALSTON CHASE?

Alston Chase is a writer and independent scholar who has spent a career specializing on intellectual history. He is the author of six books, including Playing God in Yellowstone: The Destruction of America's First National Park, and In a Dark Wood: The Fight Over Forest and the Rising Tyranny of Ecology. Chase lives in Paradise Valley, Montana.

"Bright youth now are no less alienated than they were when Kaczynski was growing up. High schools still incubate alienation, particularly among brighter students, as the authoritarian and anti-intellectual atmosphere of Kaczynski's generation continues. Colleges, high schools, even grade schools still propagate the culture of despair, scaring youth with tales of impending ecological collapse. In the universities, the crisi of reason deepens as traditional disciplines of the liberal arts—literature, philosophy, and history, the very disciplines that promote the contemplation of Ellul and Paz felt was essential for human survival—are subverted by politicizing methodologies or give ground to social sciences such as psychology, sociology, and political science, all dedicated according to their practitioners, to "prediction and control" of human behavior."

— Alston Chase, Harvard and the Unabomber

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE